CANNES, France—Wealth and those who covet it has always been a subject of fascination for Martin Scorsese, whether he's making films about gangsters (Goodfellas, Casino) or adapting Edith Wharton (The Age of Innocence). And that fascination is once again on display in his remarkable new film, Killers of the Flower Moon, which just premiered at the Cannes Film Festival. Adapting the book from David Grann about the series of murders that plagued the Osage nation in the 1920s, Scorsese has made a towering movie about America's sins and the greedy men who perpetrate them.

It's anchored by performances from Leonardo DiCaprio and Robert de Niro that both rank among their best, but the soul of the movie belongs to Lily Gladstone, who broke out in 2016's Certain Women. Yes, Killers of the Flower Moon is about stupid and selfish white men whose egos and love of money drive them to heinous crimes. And yet Gladstone, a Native actress, consistently centers the story to remind the audience whose voices have been erased from history. She gives life to both her character's pain and her spirit.

Scorsese and co-screenwriter Eric Roth have kept the large scope of Grann's reporting, but shifted the focus. Whereas Grann used his narrative to tell not just the story of the Osage people but the emergence of the modern day FBI, which ends up bringing the perpetrators to justice, the filmmakers allow us to watch the acts unfold knowing exactly who is behind them. One of the villains in question is Ernest Burkhart, played by DiCaprio, a World War I veteran with a teenage boy's naivete.

At the top of the movie, Burkhart arrives in Oklahoma at the behest of his Uncle William Hale, played by de Niro. This is Osage country, where the members of the Native American tribe that calls this place home are some of the richest people in the nation, thanks to the oil on their land. Scorsese demonstrates this with newsreel style footage highlighting the Osage finery. (It’s one of many ways he will play with historical mediums throughout the film.)

Hale, who tells Ernest he can call him “King,” immediately starts indoctrinating Burkhart into his scheme, even if Burkhart doesn’t know it yet. De Niro, transforming his New York accent into a whispery Oklahoman drawl, is the best he's been in years as this genially nefarious patriarch, who is beloved in his community yet also undermining it at every turn. His plot is to have his family marry into Osage money and then systematically dispose of the Osage women to gain access to their head rights. Ernest falls right in line by becoming smitten with the reserved but vivid Mollie Kyle (Gladstone), who he meets chauffeuring around town.

Gladstone plays Mollie as a savvy skeptic, who nonetheless finds herself charmed by DiCaprio’s wide-eyed dummy. She knows fully well he is tempted by her money, but she just can’t help herself and neither can he. He meanwhile is truly captivated by her, at the same time coveting what she has. He thinks he can occupy two roles at once: That of Hale’s accomplice and that of Millie’s dedicated husband. One by one Mollie’s sisters begin to die, all the while Ernest and Mollie develop a growing family.

DiCaprio has thrived in recent years playing men with deluded amounts of confidence, and his take on Ernest is more tragic than, say, Rick Dalton in Once Upon a Time in Hollywood… Outfitted with a pair of terrible teeth, DiCaprio manages to turn on his classic allure while also portraying a true fool. You are repulsed but you also understand why Mollie believes in his care for her. It's a smart take on a dumb guy, who, on a broader scale, is representative of an entire history of white Americans who think they can embrace a culture that is not their own while also pillaging it.

Gladstone, meanwhile, does absolutely brilliant work living in the gray areas of Mollie's emotion. In her wide eyes you can read the ardor of her love for Ernest, the sorrow of her lost family, and the intensity of her own suffering—she has diabetes, an ailment that worsens over the course of the film. It's a performance of a woman trapped not just by her own emotions, but by a greater society that wants her to occupy two worlds at once. One that has granted her wealth, but also refuses to allow her to control it: Deemed "incompetent" she must request her own funds for use from a white man who determines whether she can have what she needs or wants.

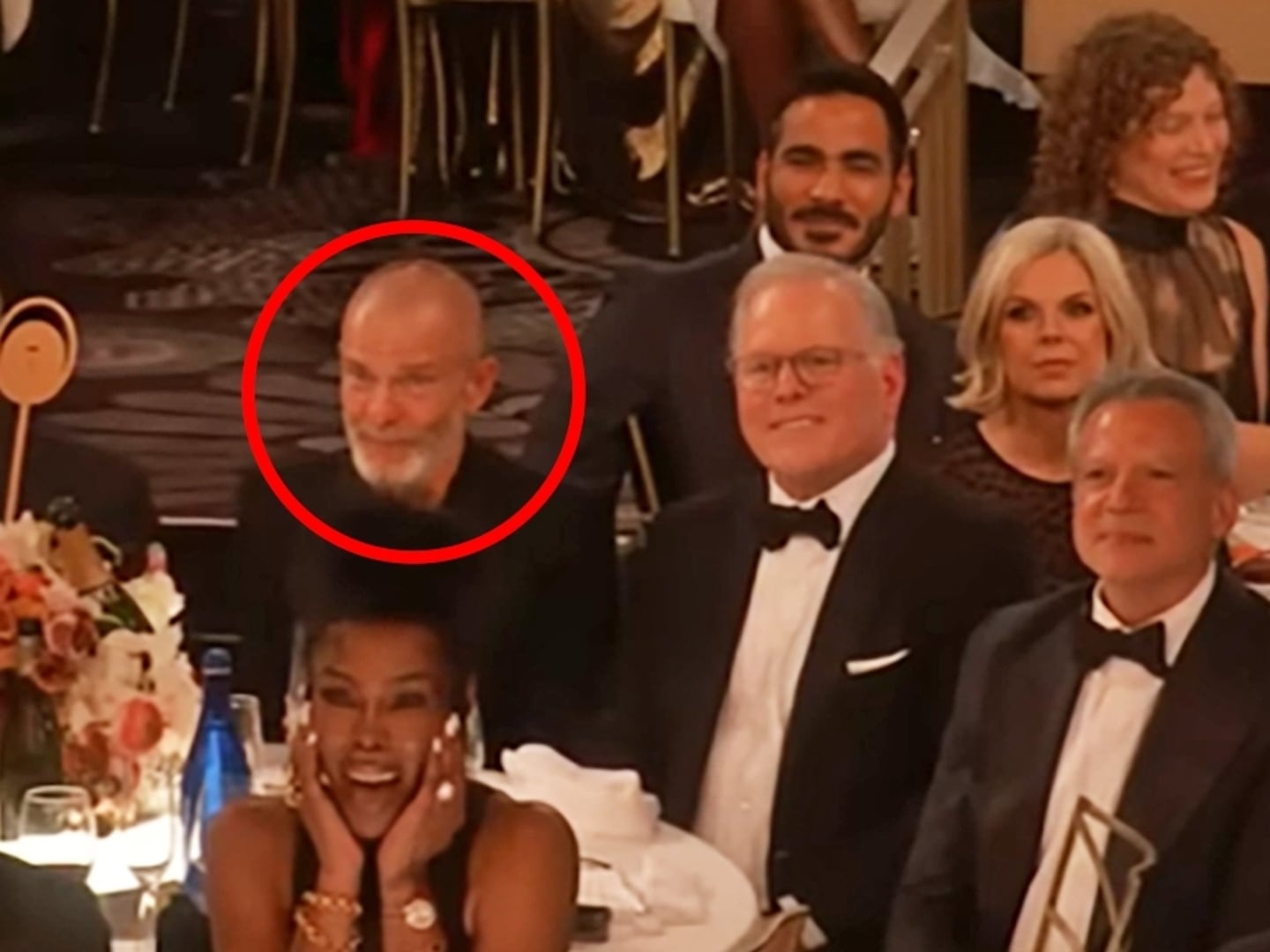

At nearly three hours and 30 minutes long, Killers of the Flower Moon never feels its length partially because of the bewitching nature of these two actors at its center—with de Niro adding a layer of smooth menace to every scene he's in. At the same time, the runtime is justified by the way Scorsese fills every frame with detail of both Osage life and the casual evil of those who want to ruin it. The both joy and simmering terror is underlined by the thrumming guitar of The Band's Robbie Robertson, who composed the score.

When Killers of the Flower Moon is released in October, I am positive there will be debates that emerge as to whether Scorsese has focused too much on those doing the crimes rather than the victims. There will be intense discussions about the big swing he takes at the end—a big picture denouement that is both striking and disorienting. But rest with the notion that this is another vital piece of art from an American master, who, at age 80, is grappling with his fixations in ingenious new ways.

Liked this review? Sign up to get our weekly See Skip newsletter every Tuesday and find out what new shows and movies are worth watching, and which aren’t.