BUENOS AIRES—The bombastic charges presented against Argentine President Cristina Kirchner by federal prosecutor Alberto Nisman just before he was found dead last month have been dismissed by a federal judge who said there was insufficient evidence to open a full investigation.

After Nisman’s mysterious demise—maybe a suicide, maybe a murder—only hours before he was to testify to Argentina’s congress about the charges that the government attempted to cover up Iran’s criminal responsibility for the 1994 terror attack against a Jewish center, AMIA, the case was picked up by another prosecutor, Gerardo Pollicita, who took it to court.

Daniel Rafecas was one of several federal judges who recused themselves at first without substantial explanations. And when Rafecas finally was forced to open his chambers to the allegations in this, the most sensational case of a generation, he gave them short shrift. The charges did not “minimally pass scrutiny,” as he put it.

But if you think this dismissal is a definitive moment in the labyrinthine saga of Nisman’s investigation and sudden death, think again. It is about as definitive as the time the charges were served. Or the time Nisman announced them. Or the time he accused a group of senior Iranian officials of planning and executing the AMIA bombing, that left 85 people dead and over 300 wounded.

In the Alice in Wonderland world that is the Argentine corridors of power, things start but never really end, sometimes not even with death. Everything is the truth and nothing is the truth, and startling incompetence dances with criminality and good intentions.

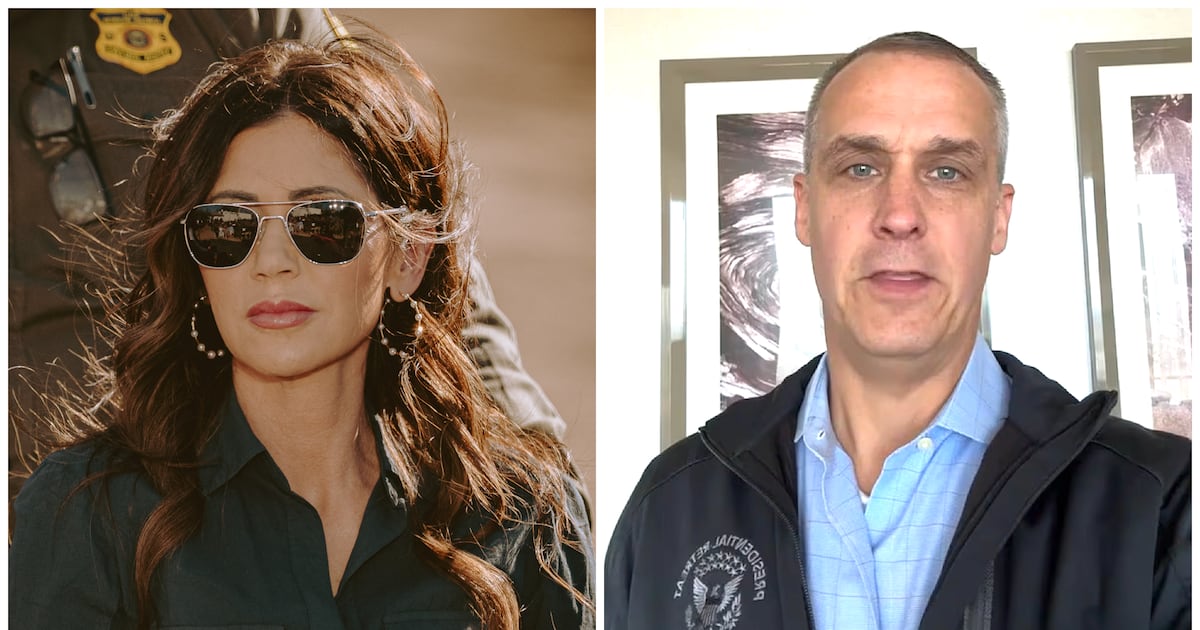

In other words: nothing starts or ends with this dismissal. It is assumed that prosecutor Pollicita will appeal, which he must do within three working days to do, and that Rafecas, who will hear the appeal on his own decision, will simply pass the buck to a higher court. The ensuing ping-pong of appeals, rejections and reconsiderations that is anticipated will last at least until December, when Mrs Kircher's term in office comes to an end, granting her a sort of purgatory in the place of the hell of the last six weeks, when Nisman announced his charges. (She is barred from running again.)

The ensuing ping-pong of appeals, rejections and reconsiderations that is anticipated will last at least until December, when Kirchner’s term in office comes to an end, granting her a sort of purgatory in the place of the hell of the last six weeks, since Nisman announced his charges. (She is barred from running again.)

Rafecas was scathing in his dismissal of Nisman’s accusations, saying, among other things, that “not even circumstantial evidence” against Kirchner held up. But he also veered into personal speculation and whimsy, for instance, when he said that were Nisman’s “grave accusations” true, it would imply that “a political personage who currently serves as president, who for the past 20 years has been loyal to the victims’ quest for truth and justice, could conceivable turn 180 degrees on these convictions, and instruct her underlings to betray those values, their country and especially, the victims of the attack, who still await truth and justice.”

Well, yes. That is exactly what Nisman accused the president of doing, in a lengthy charge sheet that pointed the finger at Kirchner for signing a secret Memorandum of Understanding with Iran in 2013, that, had it been ratified, would have, in effect, relaxed the pressure on those Iranian officials who currently are threatened by onerous Interpol arrest warrants.

In fact, in their circuitous path, both Nisman’s charges and Rafecas’s dismissal could yet end up in the very federal chambers which declared that memorandum of understanding unconstitutional. The case may well get to the Supreme Court, sitting as an appeals court, before the matter is resolved.

The Argentine government is so pleased by Rafecas’s decision that it has translated it into English (a first) and reproduced it in its entirety on the president’s personal web page.

Referring to the fact that the MOU never came into effect, thus rendering any crime merely theoretical, a judicial source close to the case said that “it is very unusual, unprecedented, for charges to be brought when clearly a crime was not committed.” If this was merely an attempt to commit a cover-up, in short, that means no cigar for Argentine courts.

The source underscored the judge’s clear political motivations for the dismissal and put a positive spin on them: “To open an investigation under these conditions would have been manifestly illegal, causing massive institutional and personal injury to Cristina [Kirchner, and her foreign minister, Héctor] Timerman, to the government, and to Argentina’s image both here and abroad. There is no way to do that. The least one can do is try, insofar as possible, to make amends for a government and people who were falsely accused.”

The judiciary is so politicized here that individual judges are referred to by their (often open) political affiliation and judges openly join factions and organizations aligned with the government or the opposition. That pattern is likely to hold and be reinforced in this case, where attention to legal detail is anything but meticulous.

Rafecas was caught in a faux pas that is being loudly mocked in Buenos Aires. In his decision, he mentions writing through the judicial recess, which, as it happens, ended in on January 31, whereas his decision was presented in late February. It was an error anyone could make, he said, he "just copy-pasted that part from another decision."

In short, Nisman’s raucous afterlife is just getting going.