“Nine years and four months,” Sylvester Owino says. That’s how long he was jailed in immigration detention, waiting for his deportation case to be resolved. He did not want to go back to Kenya, where he says he would not only be jailed but also tortured because of his political dissent.

Although his time behind bars is much longer than most immigration detainees, his plight is common. Federal records for deportation cases filed from 2000 to October 2017 show that more than a quarter-million immigrants who ultimately won the right to remain in America were jailed for at least part of the time they spent waiting for a final decision.

Many, like Owino, were held under laws requiring mandatory detention for non-citizens convicted of a wide variety of crimes—without the right to a bond hearing. Right now, the Supreme Court is deciding whether practices that would amount to “lawlessness” in criminal courts—Justice Sonia Sotomayor’s word for it—can continue in immigration courts.

The Trump administration argued strongly against a solution adopted by appeals courts in California and New York, which ruled that immigrant detainees should get a bond hearing every six months at which the government must demonstrate it would be risky to release them. Instead, its lawyer asserted that those detainees are entitled to nothing, that for “aliens arriving at our shores… whatever Congress chooses to give is due process.”

President Donald Trump, who ran on the promise of mass deportations, did not invent the present system. Rather, it was cemented into law when President Bill Clinton signed an immigration reform act the month before his 1996 re-election. The Obama administration defended it, too.

The numbers tell Owino’s story on a larger scale, and how jailing immigrants encourages them to choose to depart—giving up on the chance that a judge may allow them to stay. According to data gathered by TRAC, the Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse at Syracuse University, records for deportation cases show:

- Federal authorities have jailed 258,070 immigrants who ultimately prevailed against deportation charges filed since 2000—often after long waits behind bars. Of these immigrants, 78,947 were still in jail when their cases concluded with good news.

- The prospect of an extended stay in jail leads many immigrants to give up and ask to leave. In the year that ended Sept. 30, 7,293 of 54,290 detainees took voluntary departure, or 13 percent, compared to 242 of the 44,095 released from detention, or .005 percent. Jailed immigrants, that is, were 2,600 times more likely to give up on their cases and return to their homelands.

- About 1 in 4 of the detainees who were jailed in cases filed since 2000 but later permitted to stay in the United States—and for whom the information is available—had been living in the country 20 years or longer before being arrested.

Matthew Bourke, a spokesman for U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, said the agency decides whom to detain on a case-by-case basis “following a comprehensive review of the circumstances” that considers criminal records, risk of flight, and potential threat to public safety. Cases are then referred to immigration court, which the Justice Department runs.

Bourke said ICE has an Office of the Principal Legal Advisor that reviews cases at various stages. “During that review, OPLA attorneys may exercise prosecutorial discretion on a case-by-case basis,” he said by email. “Prosecutorial discretion has been, and will continue to be, a part of OPLA’s litigation practice.”

But a TRAC analysis shows that the Trump administration has sharply cut the number of cases closed through prosecutorial discretion: to about 100 cases a month during its first five months, from 2,400 cases a month during the same period a year earlier. And the odds are extremely poor that a detainee will be freed through prosecutorial discretion: There were just three such cases in the year that ended in September.

Owino, 42, now free on bond and running a small business in San Diego, says he used his decade in immigration jail to become a “jailhouse lawyer.” He quickly saw that under immigration law, he faced mandatory detention without a bond hearing because of his criminal record. That would be unconstitutional in a criminal case, but the Supreme Court upheld it in 2003 for immigrants facing civil deportation charges, on the grounds that there was just a “brief period necessary for their removal.”

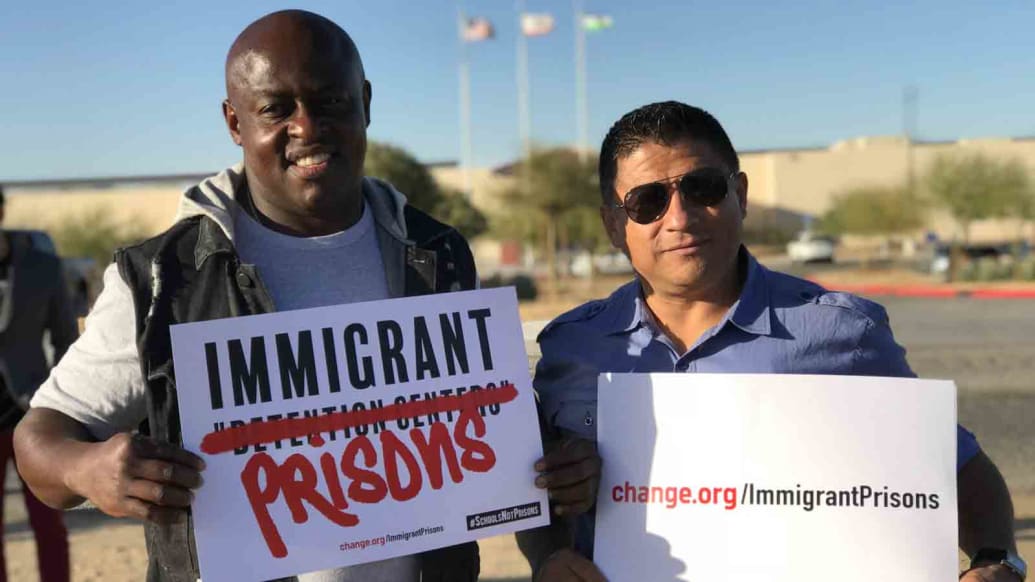

Photo courtesy of Sylvester Owino

For Owino, and many others held for years, that calculation turned out to be spectacularly wrong—not least because the justices relied on faulty data in which the Justice Department’s Executive Office of Immigration Review dramatically understated the average length of time that detainees were held. The justices then applied faulty math to the faulty data. Both errors worked against the immigrants’ case.

The government acknowledged its errors in a letter sent to the top court in 2016, 13 years after the high court’s decision—and after some 2.3 million immigrants had been detained since the errors were made.

The bottom line was that the average time spent in mandatory detention awaiting decisions from an immigration judge and the Board of Immigration Appeals was not the five months the justices had imagined. It was one year and 17 days.

According to the Executive Office of Immigration Review, it took an average of 21 days for a detainee to get an initial hearing before an immigration judge in fiscal year 2017. That’s three weeks, compared to the two days courts have generally required for defendants facing charges in criminal court.

In the case now before the Supreme Court, Jennings v. Rodriguez, the government maintains that people who had no right to be in the country should be denied bond pending deportation. “The principle that the alien has no constitutional right to be released into the community necessarily compels detention,” Deputy Solicitor General Malcolm Stewart told justices when the case was argued for a second time on Oct. 3.

Behind such legal debates are the stories of people who, like Owino, endured imprisonment in hopes of remaining in America. New York’s Immigrant Defense Project presented them in an amicus brief to the Supreme Court.

“We wanted to show that A, detention really lasts a long time and B, lasts the longest time for people who will never be deported,” said Anthony Enriquez, the lawyer who filed the group’s brief. “We wanted to show what happens in the day-to-day reality of detention. It’s a system that it’s materially indistinguishable from criminal incarceration.”

There is Sayed Omargharib, who came to the United States from Egypt in 1985 and became a lawful permanent resident five years later. In 2011, he was convicted in Virginia of grand larceny for, as a federal appeals court put it, taking “two pool cues valued in excess of $200 following a dispute with an opponent in a local pool league.” He received a suspended sentence, but ICE sought to remove him from the country because of the conviction. ICE determined that the crime was what immigration law calls an “aggravated felony,” which meant mandatory detention without the right to a bond hearing.

But the legal meaning of “aggravated felony” is often unclear, and the minority of immigration detainees able to find a lawyer have a reasonable chance of challenging ICE’s determination. Omargharib had a better chance than most, but he was imprisoned for close to two years before the immigration charges against him were dropped.

In another case, a member of Sri Lanka’s Tamil ethnic minority sought asylum in the United States on grounds that the army had repeatedly tortured him on suspicion he was a member of a guerrilla group. He was beaten with boards and gun handles, hung upside down, pricked on his toenails with needles, and burned with cigarettes, according to court records. Immigration judges twice granted Ahilan Nadarajah asylum, but the Department of Homeland Security appealed each time. He was held for more than four years until the federal appeals court in California freed him in 2006, ruling that his detention was “unreasonable, unjustified, and in violation of federal law.” He is now a U.S. citizen.

Owino, once a well-known college track-and-field athlete in Kenya, came to the United States in 1998 to study in San Diego on a student visa. He was convicted of a robbery in 2003 and, after completing his three-year sentence, was taken into immigration custody to be deported. Owino sought asylum on grounds that he had fled from Kenya after police there beat him for publicly criticizing the government.

Owino’s robbery conviction was clearly an aggravated felony, so although he had served his time for the crime, he was held in mandatory detention starting in November 2005. Then came the nine years, four months—far beyond any “brief period” the Supreme Court provided for.

His mother and brother in Kenya died. He made friends in jail. He noticed some of them were being deported for crimes that were, unlike his, petty. Like most detainees, he couldn’t afford a lawyer. In criminal courts, even those facing very minor charges are provided with counsel if they can’t afford it. That’s not so in a deportation case, which is considered a civil proceeding.

“ICE told me flat out that I’m a danger to the public, I’m a flight risk,” Owino said. “I said, ‘OK, my only hope is the higher courts,’ and I knew it takes two or three years. I decided I’m going to take this time to help others, and to help myself.”

He went to the law library, looking to help himself and fellow detainees. But, he said, ICE officers made him the “primary example” to other detainees of how long they might be jailed if they sought to pursue the paths the law allowed. “It was a difficult battle,” he said.

One of the problems of being incarcerated without a lawyer is that it’s difficult to gather evidence to prove a claim—in Owino’s case, that he would be tortured if sent back to Kenya. There were simple logistical problems, such as getting legal mail on time. “You wind up getting deported because the detention officers held onto your mail,” he said, explaining that some detainees missed legal deadlines as a result. “If you tried to help another detainee, they’d move you or retaliate against you.”

In 2009, Owino won two appeals court rulings on the same day. One reversed a decision that ordered his deportation because he hadn’t been permitted to submit new evidence. In the other, the appeals court ordered that Owino be re-evaluated for a bond hearing—that if it was determined he had a reasonable chance to win his case, then he should be released. The judges also said he should be appointed a lawyer.

Still, Owino remained in jail at the Otay Detention Center on the outskirts of San Diego; he preferred it to facing the possibility of both jail and torture in Kenya. “I knew I had a strong case,” he said, adding that federal authorities “had put my life in more danger than I was before” by showing documents in his case to Kenyan police. Two immigration courts rejected that claim, but a federal appeals court later ruled that a government investigator may indeed have alerted the Kenyan authorities to his asylum case, contrary to regulations.

In the meantime, the federal appeals court in San Francisco issued a major decision in 2013 in the case of dental assistant Alejandro Rodriguez, who had come to the United States as an infant and was jailed pending deportation because of what a court called a “joyriding” conviction. The court ruled that immigration detainees must be granted the “minimal procedural safeguard” of a bond hearing every six months. It also shifted the burden of proof from detainees to the government, requiring that it demonstrate danger to the community or risk the detainee would flee. The federal appeals court in New York reached a similar decision in a separate case in 2015.

The result was that in some parts of the country, but not others, long-term detainees were able to request bond—a discrepancy to be resolved in the pending Supreme Court case.

Studies show that immigration judges in New York and California released most of the long-term detainees who received bond hearings because of these rulings.

But Owino almost missed his chance to seek bond; after the Rodriguez ruling, he was transferred to the Etowah County Detention Center in Gadsden, Alabama, where the decision didn’t apply. “It was done purposely by ICE because there was a bunch of us who had been in, detained for a long time, two or three years, more than six months,” he said. “ICE knew that a lot of guys would get out.”

The Etowah facility, connected to the county jail, is considered by immigrant advocates to be one of the worst immigration jails in the country.

The Department of Homeland Security’s Office of Civil Rights and Civil Liberties has investigated complaints about Etowah many times over the years over medical neglect, rotting food, and assaults on detainees.

In 2016, it issued a “super-recommendation”—a jolt for ICE officials to recognize there has been a long-term failure at the jail to act on “serious civil liberties concerns” and urging that “that ICE no longer use the facility to house detainees.”

With help from his lawyer and the advocacy group Community Initiatives for Visiting Immigrants in Confinement, as well as local people who visited the jail, Owino managed to transfer back to the San Diego jail. He said he filed requests for five other detainees to be returned as well.

After his transfer from Etowah, Owino took a leading role in a complaint to federal authorities alleging a pattern of beatings in which ICE officers at the Alabama jail handcuffed detainees and beat them.

And finally, he was freed on the minimum bond of $1,500 in March 2015.

With his case still undecided, he started a business selling Kenyan food at a farmer’s market, simmering chicken stews and plantains. And he continued his advocacy, becoming the lead plaintiff in a class-action lawsuit against CoreCivic (PDF), formerly Corrections Corporation of America, which runs the San Diego jail where he was held. The lawsuit charges the company, which reported $1.79 billion in revenue in 2016, coerced detainees into “volunteering” to do cleaning and other work for $1 a day.

It’s not clear how many others have endured such long-term imprisonment while fighting deportation. Federal data gathered by TRAC shows that as of October, there were at least 162 people being detained on deportation cases that began nine or more years ago. But the numbers don’t tell whether they have been imprisoned continuously.

“The immigration system is broken and it needs to be fixed,” Owino says. “And when I say needs to be fixed, I don’t mean to deport people and separate families. Give them a chance.”