I remember the girl had pale freckled skin and carried a makeup clutch. She had been watching me since I’d been placed in Mr. Carter’s homeroom. I could tell that something about me unnerved her. One day she turned, squinted her eyes at me and asked, “Where are you from?”

My cheeks flushed; I felt light and queasy. What could I tell her? Maybe that I was Jewish. Maybe say I was Puerto Rican and leave the rest up to conjecture. But I was so embarrassed and desperate to fit in, I could never tell her where I was from.

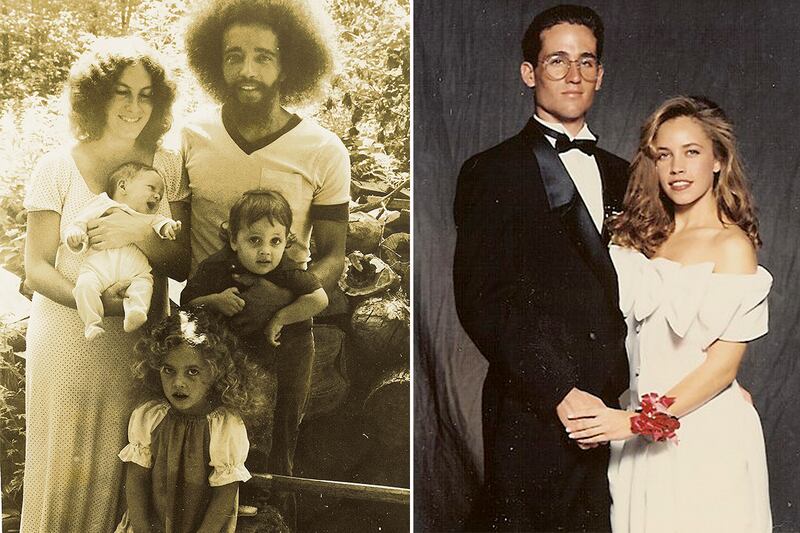

Two years earlier, in September 1985, my mother, sister, and I had packed everything we owned into the back of our green Volvo station wagon and drove west out of Tennessee. I’d lived all 12 years of my life in the backwoods there, on the largest commune in America, known as The Farm. At its peak The Farm had 1,500 members; it was a self-contained world with its own school, farm, midwives and social tenets.

But after years of living in poverty and following several undercover FBI investigations, The Farm started to unravel. Our family, along with hundreds of others, left in a mass exodus and dispersed along highways across the country to join mainstream America.

As we headed out, our old yellow-walled trailer disappeared into the dust of the road.

My father, Jose, wasn’t with us. The commune had been the glue connecting our parents—an unlikely coupling of a Jewish girl from Beverly Hills and a Puerto Rican from the Bronx—and when it fell apart, so did they. Jose and his new wife took my younger brother, Miguel, and went in the opposite direction.

Meanwhile the three of us arrived in Los Angeles via Interstate 10. We took it to the end, just before it dived into the ocean, where my grandfather, a successful surgeon, lived in the wealthy Pacific Palisades. Before that trip, I could count on one hand the number of times I’d seen the world outside the commune. I had never smelled perfume, used money, eaten meat, seen women with makeup or men without beards. Los Angeles might as well have been another country.

At my grandfather’s house, my new backyard was a sprawling oasis with a giant swimming pool, fruit trees, and a croquet court. Our neighbors were Eddie Albert and Goldie Hawn. I remember one day standing at my bedroom window, watching a woman and a young girl strolling down Amalfi Drive, all their blondness aglow. It was Goldie and her daughter, Kate Hudson. At the time I had no idea who they were.

We soon moved into our own apartment, a dilapidated two-bedroom on the east side of Santa Monica—but still in the good school district, our mom assured us. Our one piece of furniture was a rust-colored velour couch. It was a step up from commune dwellings, but it didn’t feel that way. Even though we lived below the poverty line on The Farm, I felt much poorer in L.A. Back in Tennessee, secondhand shoes wrapped with duct tape seemed normal. Everyone shared resources. Mothers even nursed each other’s babies. People trusted each other, and economic status didn’t define us the way I knew it had begun to define me.

When I entered middle school, I was crushingly self-conscious of my otherness.

Not only was I poor—I was a frizzy-haired Puerto Rican-Jewish girl from a commune in the deep South. There was nothing about me that fit into Santa Monica, with its grand single-family homes and casual elegance. In mid-1980s America, I would rather have admitted I was from Mars than a commune. I needed to survive, so I began to obscure a past I was certain no one would understand.

For an entire year I sat in the back of my classes, practically mute. I watched a new social order unfold and studied its cues. I was riveted by one exchange between a girl and boy in my class. With a barely noticeable tilt of the head and swish of the back of the palm, the girl flipped her straight golden mane back and forth as the boy sat transfixed.

More than anything else, I wanted to fit in. Like any other kid, I needed to be accepted by my peers. It was the only thing that mattered.

I began to devour American pop culture. I begged my mom for a pair of Guess jeans, which she could barely afford on her secretary’s salary. I wore smudged black eyeliner, stacked dozens of Madonna-style plastic bracelets on my wrists and wore doorknocker hoop earrings. I blasted the Beastie Boys and chemically straightened my curls, drenching them with Sun-In until I, too, had long, golden waves.

Three years after I arrived, it paid off. One day after school, a reporter for the Los Angeles Times approached me and asked to take my picture. I didn’t know what to expect, but a week later, I was on the front page of the style section under the headline “Teen Togs,” wearing an Axl Rose bandanna and a bolero hat. In the story, my new friends and I talked about the hottest fashions of the day. The article was a personal milestone. I had succeeded, but not in the way that would have seemed obvious. I did not want to be famous; I just wanted to pass.

When I went to college at UC Berkeley, I pledged Delta Delta Delta. Soon I was surrounded by a gaggle of beautiful girls, all of whom had 4.0 grade-point averages and were puking up every meal in the bathroom. After two months, I stopped going to their meetings. One evening two senior members came to my dorm room unannounced and pleaded with me to return. At the time, I didn’t know what to say. I didn’t want to outright reject them because I’d worked hard to win their acceptance. But the sorority was so dysfunctional I could no longer ignore the toll it was taking on my self-esteem.

I felt lighter when I walked on to campus the next morning. My decision to leave the sorority gave me a renewed sense of pride. I knew I didn’t have to hesitate when asked, “Where are you from?”