This time around, they are more than a faint echo. This time the roars of support for the stars of the Paralympics echo across London.

The Paralympics have been the poor relation of the Olympic Games since their first appearance on the same stage at the Rome Olympics of 1960. Back then, no one was ready for them: accessibility ideas were in their infancy, and the athletes had to be carried bodily upstairs to the changing rooms. Although they became a fixture of subsequent Games, until London it was assumed that the general public was indifferent at best, derisive at worst. A patronizing tone of charitable encouragement dogged them. To fill the stadiums, schoolchildren had to be bused in.

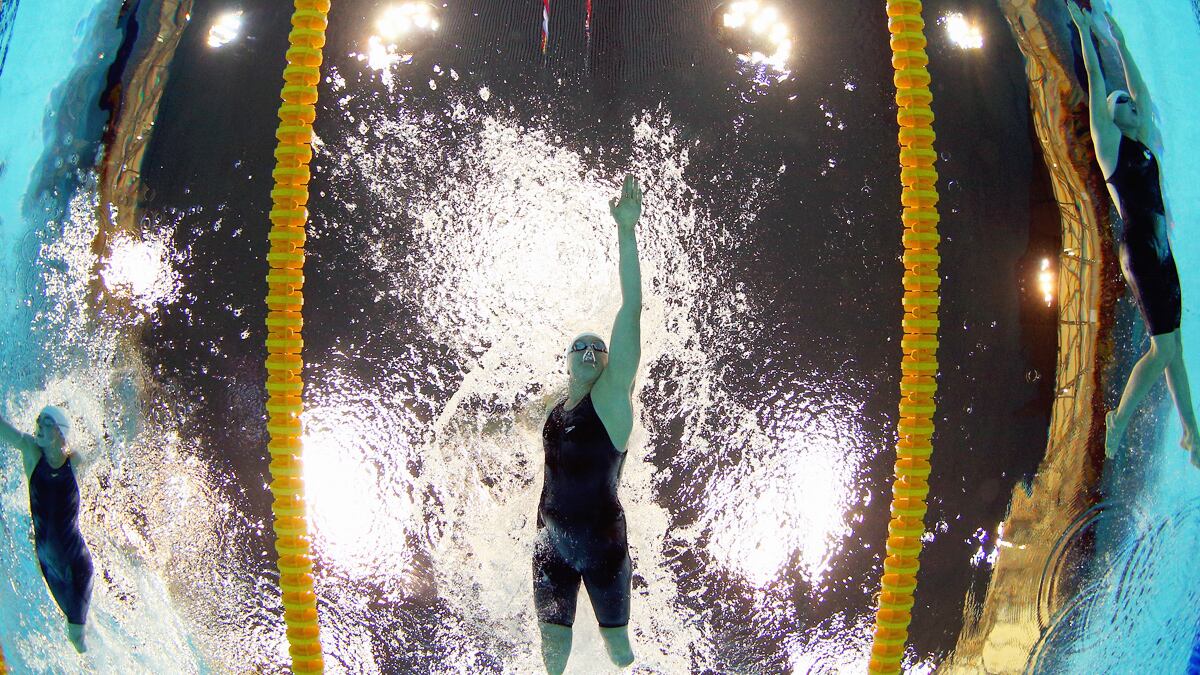

But this year in London, the Games are sold out. News bulletins and newspapers are bursting with Paralympic news and stories. Lottery funding, lavish advertising and political support, capitalizing on the fact that these Games were invented in Britain, if not by a Briton, have had the desired effect: a handful of the champions, people like South African double-amputee sprinter Oscar Pistorius, known as the Blade Runner, are on the cusp of becoming real celebrities. Exotic knockabout sports like wheelchair rugby and goalball (a contest between visually impaired teams involving a ball with bells in it) are drawing avid attention, simply because they are gripping to watch. For the Paralympians, 2012 will be the year they broke out of the ghetto.

The genesis of the Games goes back to British casualties of D-Day and a Jewish doctor named Ludwig Guttmann, a refugee from the Nazis who declared war on the prevailing idea that paraplegics were, in the brutal phrase of the time, “moribund incurables.”

Appointed head of the spinal-injury department at Stoke Mandeville hospital near Oxford, Guttmann revolutionized the treatment of patients who had been swathed in plaster and left to rot in bed. Against fierce resistance and rooted prejudice, he got them out of bed and into the gym and the swimming pool. And when he found a group of them playing an improvised game of wheelchair hockey using upturned walking sticks, he saw that their competitive urge was as strong as ever—they were, after all, young ex-soldiers—and dragooned them into learning javelin-hurling and archery. The first, tiny prototype of the Paralympics was held on the grounds of the hospital in 1948, shadowing the Olympics held in London at the same time.

This year, the British government has pumped the Paralympics for the feel-good factor, and they have been a useful summer distraction from the woes of an economy that continues to tank. The propaganda effort has not, however, blinded everybody to the cruel irony that it is this same government that has taken an axe to welfare provisions for the disabled, slashing their benefits and aiming to force them back into work. Nor has it gone unnoticed that the French firm Atos, one of the corporate sponsors of the Games, is the same firm that is testing the disabled population for their fitness for work. Half of Britain’s disabled, meanwhile, are already below the poverty line.

And although the newfound fame of the top Paralympians has transformed the appeal of the Games, there are those who see a dark side. For Danielle Peers, a Canadian who won bronze in wheelchair basketball in 2004 in Athens and who still coaches the sport in Alberta, the idolization is a big problem.

“We see them as heroic for overcoming what we imagine to be their tragic, disabled bodies,” she told The Daily Beast. “We hold such low expectations of people we see as disabled that their Paralympic accomplishments seem amazing, superhuman events. And this ends up reinforcing the idea that disability is really in these people’s bodies. But that’s akin to seeing racism as a problem of skin color.”

In this way, far from disolving the divide, the pernicious sense that these people are essentially different from the rest of us is reinforced.