Could the home-foreclosure crisis swing the presidential election?

It’s a possibility, if the results of a new study out of California hold true around the country.

Until now, most of the attention on voter turnout has focused on ramped-up voter-ID laws, which have been criticized for disproportionately discouraging low-income and minority voters from going to the polls in November.

But a study published in the September issue of the journal Social Science Quarterly found that a California neighborhood’s home-foreclosure rate was inversely correlated with voter turnout. More surprising, the researchers found, the effect was heightened not only among those who had lost their homes, but also among the people who lived near them. In other words, what mattered was the neighborhood.

The study’s authors, Martin Johnson and Vanesa Estrada-Correa, both professors at the University of California, Riverside, said they believe their analysis is the first of its kind.

“There’s been a lot of research on the positive side of the relationship,” Johnson said—that is, on the connections among home ownership, residential stability, and political participation—“but not a lot of research on the negative side, on what happens when people are dislocated.”

In the study, Johnson and Estrada-Correa looked at foreclosure data for 64 percent of California’s zip codes. Using 2008 primary-election turnout as a baseline measure of political participation, and controlling for factors highly correlated with voter turnout, like race and income, they found that simply living in a neighborhood with a high foreclosure rate makes it less likely that you will vote—even if you haven’t lost your home.

Overall, the study found, neighborhoods with very low foreclosure rates saw about a 0.2% drop in turnout below what was expected, while those with a very high rate saw a drop of more than 1 percent.

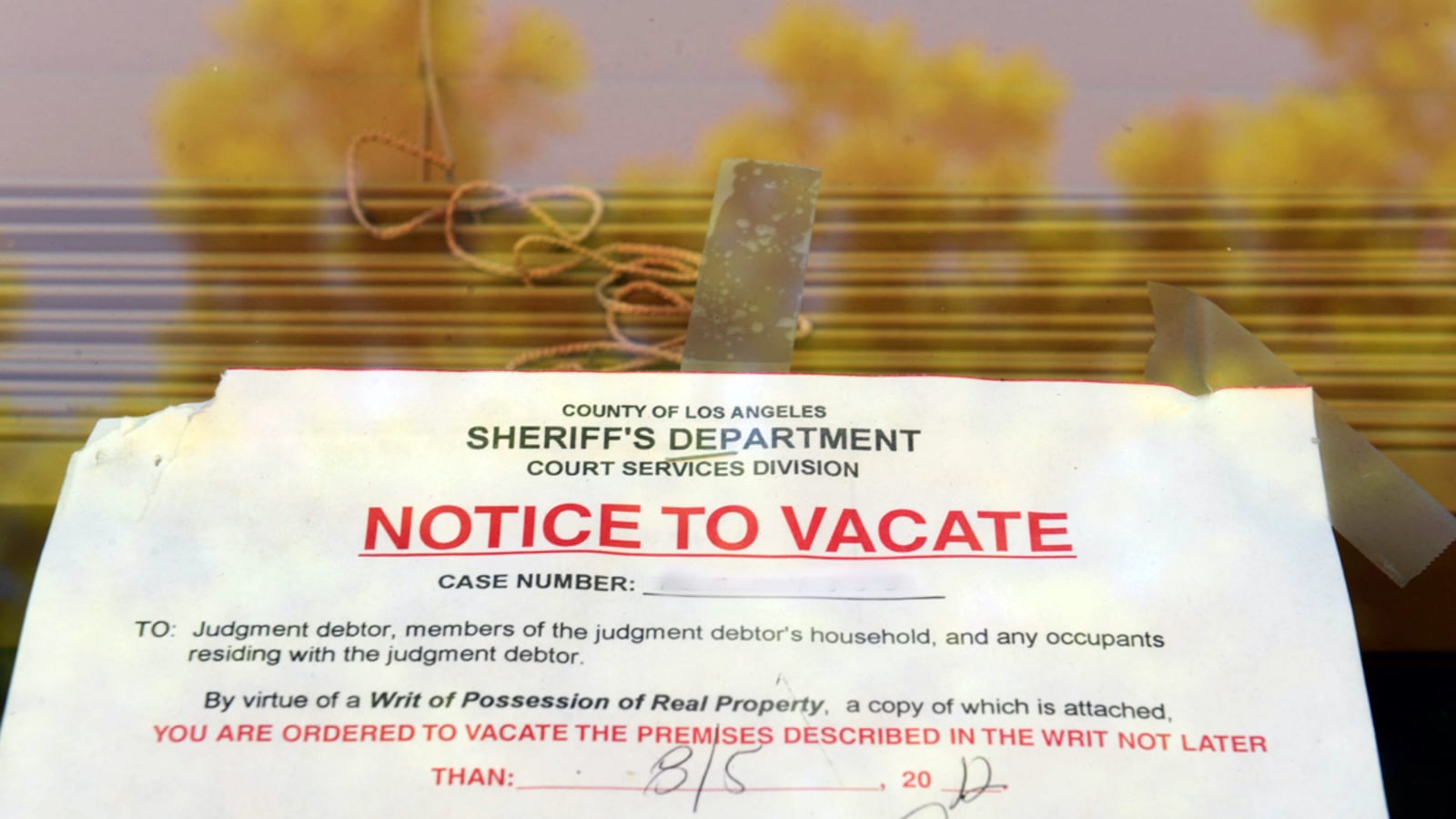

It makes sense that people whose homes have been foreclosed are less likely to vote: losing a home brings with it a nightmare of dislocation and often litigation, making it more difficult to take the time to register and go to the polling station.

But what about for those who merely live nearby? One possible explanation for the “proximity effect,” Johnson said, is the idea of social capital—the building of helpful, stable human networks. In a well-functioning community, he said, “you own your home, you’re more economically stable, you’re more invested in the community, you have more stakes in the community, you’re paying taxes, you’re doing all the stuff that homeowners do.

“In addition, you become more rooted—you become more socially connected to your neighborhood.” In other words, the more social capital around you, the more likely you are to get out and vote.

“Interpersonally, we’re able to trust each other, use each other for information and support,” Johnson said. But when that capital is depleted, as it is when families are kicked out of their homes, the effects are felt by the larger community.

“And when someone is then pulled out of that neighborhood as a function of home loss, that disrupts that community.”

(It’s also true that voter-outreach folks have a harder time simply locating voters in the states most wracked by foreclosure.)

So how might this play out in a national election? Of the 10 states with the highest foreclosure rates in 2012, five—Florida, Ohio, Michigan, Nevada, and Indiana—are toss-ups.

Johnson cautioned that at the neighborhood level, foreclosure rates produce “small, marginal effects on the overall turnout rate.” But applied to an entire state in a close race, they could alter the outcome. This could be more likely to hurt Democrats, since minority and lower-income voters—who are disproportionately affected by foreclosures—overwhelmingly vote Democratic.

It remains unlikely that foreclosures alone will flip a state from Obama to Romney or vice-versa. But in a true toss-up race—say, in Florida—little shifts can make a big difference. After all, in 2008, Obama won the state by just 236,000 votes out of 8 million cast. And then, of course, there was the election of 2000.