Few males, I would venture to guess, can—upon reflection years later—recall the instance or incident whereupon they started to become men; where, when and what happened that caused them to take their first, tentative, mental steps onto the bridge that would ultimately lead them across the yawning chasm that separates soft, carefree puberty from the onset—the hardening—of eventual manhood. Fortunately for me, I can recall the time and date of the beginning of my personal transition and journey with such an evocative clarity I swear it seems as if the vignette played out only yesterday.

It was not something I did—but rather—something I, in the waning moments of my childhood, was about to witness. It was to be one of those father/son lessons that have been transmitted down from generation to generation since the beginning of time.

It had been a stiflingly hot summer day in the neighborhood where I was born, at home, above the pool room that sat next door to the tavern and barbecue joint owned by my father. It sat on the northwest corner of Scovill Avenue and East 31st Street in Cleveland, on land now occupied by a high school—on a renamed street.

The corner across 31st Street was occupied by the only new building that had been built in the area in 30 years, Silks Bar. Old man Bob Roberts had built it and his son, a foreman with the city sanitation department, ran it. Silks was definitely more upscale than my father’s joint, King’s Tavern and Grill... which was pretty dumpy by comparison, but never seemed to lack for customers. Due to the proximity of the two watering holes—and the pool room to boot—this was one of the busiest corners on the entire black East Side of Cleveland back in the day. At times the streets literally teemed with people.

Day was fading to early evening and the “corner,” as it was called, was crowded with people just out trying to get some relief from the heat. After all, it was Friday, and this was where everyone hung out. I was leaning on the fender of my father’s Cadillac that was parked directly in front of his tavern, listening to him. He was telling me about a fishing spot he was going to take me and my brother (and usually a bunch of other kids from the neighborhood) to the next day. It was someplace we’d never been to before. Always regaling me (and just about everyone else he came into contact with) with yarns and tall tales, he was saying the fishing there was so good… you had to hide behind a tree to bait your hook.

Oftentimes during the day and early evening hours—while there was still light enough to see—there would be men shooting craps on the side street (my bedroom window was right above it so I learned colorful and salty language at an early age) but the police never caught anyone playing dice since there was always a lookout posted on the corner of Scovill to shout “raise up” before a cop car got within a block of the corner. But this night there was no crap game, no nothing, just people trying to cool off.

So there was no need for anyone to yell “raise up” when the cop car pulled up on the corner, and actually jumped the curb with two wheels, forcing people to scramble to get out of the way to avoid being hit. Two big, beefy Irish cops got out of the patrol car and began walking though the crowd of people, swinging their nightsticks at people’s knees, forcing them to scatter.

“Move it, move it,” the cops said, and people began to slowly move away… or at least out of the range of the nightsticks. Some of the men, and a few of the women, were grumbling (albeit, half under their breath) as they moved that no one was breaking any laws, so why were they being dispersed? I automatically began to move, even though the cops were not that close to us yet, but they certainly were heading our way. My father, who had huge, strong hands grabbed me on the upper arm and said, “Where are you going? Don’t move.”

Now, no one was going to openly challenge the authority of the police; in my neighborhood, in the mid-'50s, when a cop said move, you moved. The bigger of the two cops came our way, and I was, as the saying goes, feeling trapped between a rock and a hard place—between my father who has told me not to move, and the cop, who is saying something else. While I feared the cop, I respected my father more, and respect won out over fear. I didn’t move.

“You too, Mansfield,” the cop said to my father (his name was Mansfield also, I’m a junior) “move it.”

My father, who had been looking dead ahead, not to the side from where Murphy was approaching, turned to face the cop and in the calmest of voices, but loud enough for everyone to hear, and looking directly into the big cop’s eyes, said, “Murphy, I’m leaning on my car, in front of my business, talking to my son, and if you try to hit me on the knee with that nightstick I’m going to take it from you and shove it up your ass.” My father then slowly turned his head away from Murphy (who was beginning to turn what would eventually be a bright shade of beet red) in a dismissive manner, as if to say, “go ahead, take your best shot, do whatever you got the guts to do, ‘cause I ain’t scared, I didn’t mumble, and I definitely ain’t moving.”

My whole universe froze; everyone who had been moving away stood stock still, as if transfixed, waiting to see what would happen next. I’d never seen anyone challenge a police officer before, and I doubt if any of the other folks on that corner that evening had ever witnessed it either, at least not with the person living to tell the tale. This was uncharted territory we were entering, and no one knew what the outcome would be... but, if the past were to serve as an indicator of what was about to happen next, it was about to get real ugly on the corner of 31st and Scovill that evening. White cops just didn’t take that kind of talk off a black man, any black man... no way, no how. And my father clearly was not in the mood to take anything off of any white cop that evening. Something was going to have to give... or explode. My father always had an Army-issue Colt .45 pistol in his pocket under his bartender’s apron.

Being largely sheltered—at least to that point in my young life—from the sting of racism by a strong black father, I didn’t have the pent-up hatreds boiling inside of me that the black adults who were witnessing this event unfold must have harbored. Hatreds spawned by the daily insults—both large and small—that had to be stoically endured by virtually all African Americans just to make it through the day if they functioned in the white-owned and controlled world. Society and their parents had taught them it was safer to “take low,” as the old folks used to say, to be less—non-threatening—to cast your eyes down, and, when you are told by someone in a position of authority (most often someone white) to move, you just moved, no questions asked.

But my father wasn’t moving. His stand on this hot summer night wasn’t—I don’t think—planned or premeditated; and he certainly wasn’t seeking to become any kind of martyr, living or dead. No, I think, these many years later, that he was—consciously or unconsciously—teaching me a lesson about manhood simply by being a man.

Murphy, who was taken completely aback by my father’s forthrightness, was totally at a loss as to what to do. They didn’t teach this at the police academy... niggas just moved when they were told to move, that was how it went down in the ghetto.

And then, after what seemed like an eternity, Murphy turned on his heels, and with as much gruffness in his voice as he could still muster, said to his partner, “let’s go,” as if they had very important business elsewhere.

It was at that exact moment that I started to grow up—that I started on my journey to manhood. It was from that point forward that I began to measure all of my actions in life by one simple question: What would my father do? And, while I have certainly at times strayed from the path that he set for me, the path he would have wanted me to take, I have never lost sight of the values, the pride and courage, and the sense of manhood that he implanted in me. To this very day (even though he is now 37 years in his grave), he—as it should be—remains my guiding light, my conscience, my bright, shining hero.

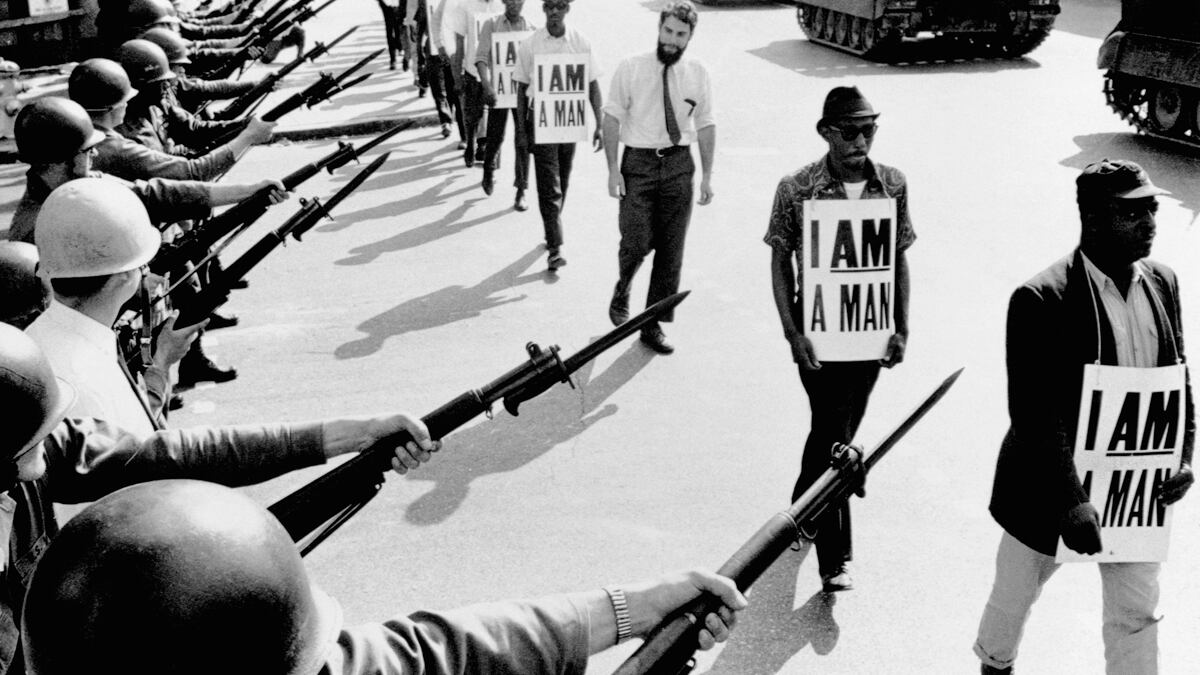

Of course the incident became part of the lore and legend of our neighborhood … growing exponentially over the years with virtually each retelling: the time that Mansfield stood up to the police. While he might have taken his stand as a lesson for me in how to be man, everyone there that evening (and some people who weren’t even there but later heard about it) claimed the incident... he was taking this stand for them too, for each and every one of them. He had, by simply standing his ground, reclaimed for them a little piece of their dignity, some of their humanity that is often lost by black folk in America, sacrificed to the ugly gods of institutionalized racism on a daily basis.

I would see my father stand up for himself—and for others—many times over the years in the rough and tumble Cleveland neighborhood where I grew up, but this was the incident that, at age 12, marked the beginning of my personal journey. It was in August 1955, and slightly less then four months later, on December 1, 1955, Rosa Parks would refuse to give up her seat on a Birmingham bus. Looking back over the past 50-plus years, I often wonder if the two events were somehow, in some metaphysical or spiritual way, connected... in my own mind I like to think they were.