Who won, who lost, and how much it all cost—John Sutherland on his evening at the Man Booker Prize ceremony and Hilary Mantel’s victory. PLUS, view our gallery of the past 10 winners.

The winner of literature's prestigious Man Booker gets £50,000 for a work that can take years. It’s less than a third of what the Manchester United striker Wayne Rooney (who, I suspect, has never read a novel) gets in a week. Shortlisted candidates pick up a check for £2,500—and a year’s free membership in Soho’s Groucho Club. Pity the country, to paraphrase Brecht, that needs literary heroes.

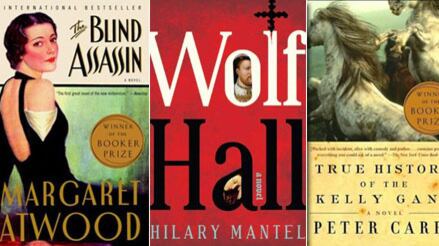

Click Image for a Gallery of Booker Winners

The Man Booker ceremony is no longer, as it once was, televised. But there is still considerable excitement in the run-up and on the night. Unpredictability sharpens the excitement. The Goncourt, the French literary prize, has lifelong judges—often themselves novelists. Man Booker recruits a new panel annually. This year it comprised a radio journalist (Naughtie), a TV comedian, a professor of literature, a literary editor, and a professional writer of nonfiction. Throw in 132 novels and you have fireworks.

Every year there’s a flavor to the shortlist. Sometimes it’s postcolonial (no one with an English-sounding name need apply). Sometimes (twice in the last four years) it’s Irish. Sometimes it’s old codgers rewarded for long service and good conduct (Kingsley Amis and William Golding benefited with novels that were anything but their best). Sometimes it’s young hopefuls with no track record (last year’s Aravind Adiga).

The 2009 flavor was as English as roast beef and Yorkshire pudding. All but one of the shortlisted six (Coetzee being the exception) hailed from the mother country. And each of those five novelists went deep into English history for their plots. The winner was Hilary Mantel, who went furthest back into the Tudor period with a bio-novel about Henry VIII’s adviser, Thomas Cromwell. It was also the people’s choice. Bookies had Wolf Hall at evens. Booker lore is that the favorite never wins. This year it did. Handily.

My guess is that, good read though it is, Wolf Hall won’t do outstandingly well in the U.S. or anywhere that 16th-century English history is not prominent on the high school syllabus. But symptomatically the surge behind the novel is telling. Britain, for the last few months, has been in a hysterical dilemma about whether it really wants to go into Europe—by signing up to the Lisbon Treaty. There’s a general election in seven months’ time. The electorate is paralyzed between a party it has come to hate (Labour) and one that it does not yet love (the Conservatives). The Queen of England is 83 years old. The heir apparent (a stripling of 61) is not universally popular. A succession crisis is possible. It’s the 1530s all over again.

Wolf Hall is a fine novel. I would happily have voted for it this year if I’d been a judge. But the ultra-Englishness speaks to me of a country that is going through one of its recurrent anxieties about what it is to be English. I am myself, as it happens.

When the Booker Prize was launched as the “British Goncourt” in 1969, it was met by a universal guffaw. “Not English” was the Podsnapian cry from the throat of Literary London. Britain despised French academicism. But at least the Goncourt, with its derisory 50NF cash reward, had clean hands. The purse (£5,000) pocketed by the first Bookers was a stain on literature. It wasn’t just the loot. Booker-McConnell was a firm with interests (principally sugar and rum) in the West Indies. The prize has since been taken over by the Man Group PLC, “a world leading alternative investment management business” (they get extremely annoyed if, as people commonly do, you call them a hedge fund).

Notoriously, the 1972 laureate, John Berger, used his winner’s speech to excoriate the Simon Legrees who sponsored the prize and announced his intention to donate half his prize money to the British Black Panthers. The gesture was somewhat vitiated by the fact that the Panthers no longer existed. But novelists rarely take much notice of the real world, making, as they do, such fascinatingly unreal worlds of their own.

Britain’s book world has not traditionally subscribed to the American view that books compete with each other like gladiators in the Colosseum. This fond belief explains why until 1975 Britain had no reliable bestseller list—a machine that had dominated the retail sale of books in the U.S. since the 1890s.

Historians of the Booker record its transition from annual joke to a revered institution as 1981. That was the year that Salman Rushdie won with Midnight’s Children. That work has since been crowned (twice) as the “Booker of Bookers.” Its triumph coincided with a relevant historical event: the rise of Thatcherism. The early ’80s was when the Iron Lady conquered the trade unions, ushering in a world (“free enterprise”) in which competition was not merely good but God. It transformed Booker, along with everything else. Some would use a harder word than “transformed.”

The Man Booker Prize is now installed as a key element of the “Establishment”—that complex social organism made up of class, money, and prestige that writes the rules in the U.K. Novelists do not automatically qualify for membership. Every year, the shortlisted six come blinking into the blaze of the award night like Mole in the first chapter of The Wind and the Willows. As they sit at their high table (the men in hired evening dress) at the sumptuous Guildhall, waiting for the envelope to be opened, around them, clattering their knives and forks and drinking good wine, are the massed ranks of the British Great and Good.

The event reeks of money. I have been told the banquet costs half a million. Rather less trickles down to the literary front line. Judges get £7,000. For this, in 2009, they were expected to read 132 books. The math is daunting. More so since the five judges are all in full-time employment. How did he do it? I asked James Naughtie, the 2009 chair. “Most of the novels are bloody awful,” he bluntly explained. “If you don’t believe me, check the dents in my bedroom walls.”

Naughtie, as it happens, has a job that rather restricts his time in the bedroom. As a presenter on the BBC news program Today, he has to get up, three days a week, at 4 a.m. BBC salaries are a closely guarded secret, but I would be surprised if Naughtie clears less than a quarter of a million. Why would he surrender his precious few hours of snooze for a measly seven grand? For an academic like myself (chair of the Man Booker judges in 2005), the amount is nontrivial. But for the Naughties of the world, it’s peanuts. One assumes the work is undertaken pro bono.

Plus: Check out Book Beast, for more news on hot titles and authors and excerpts from the latest books.