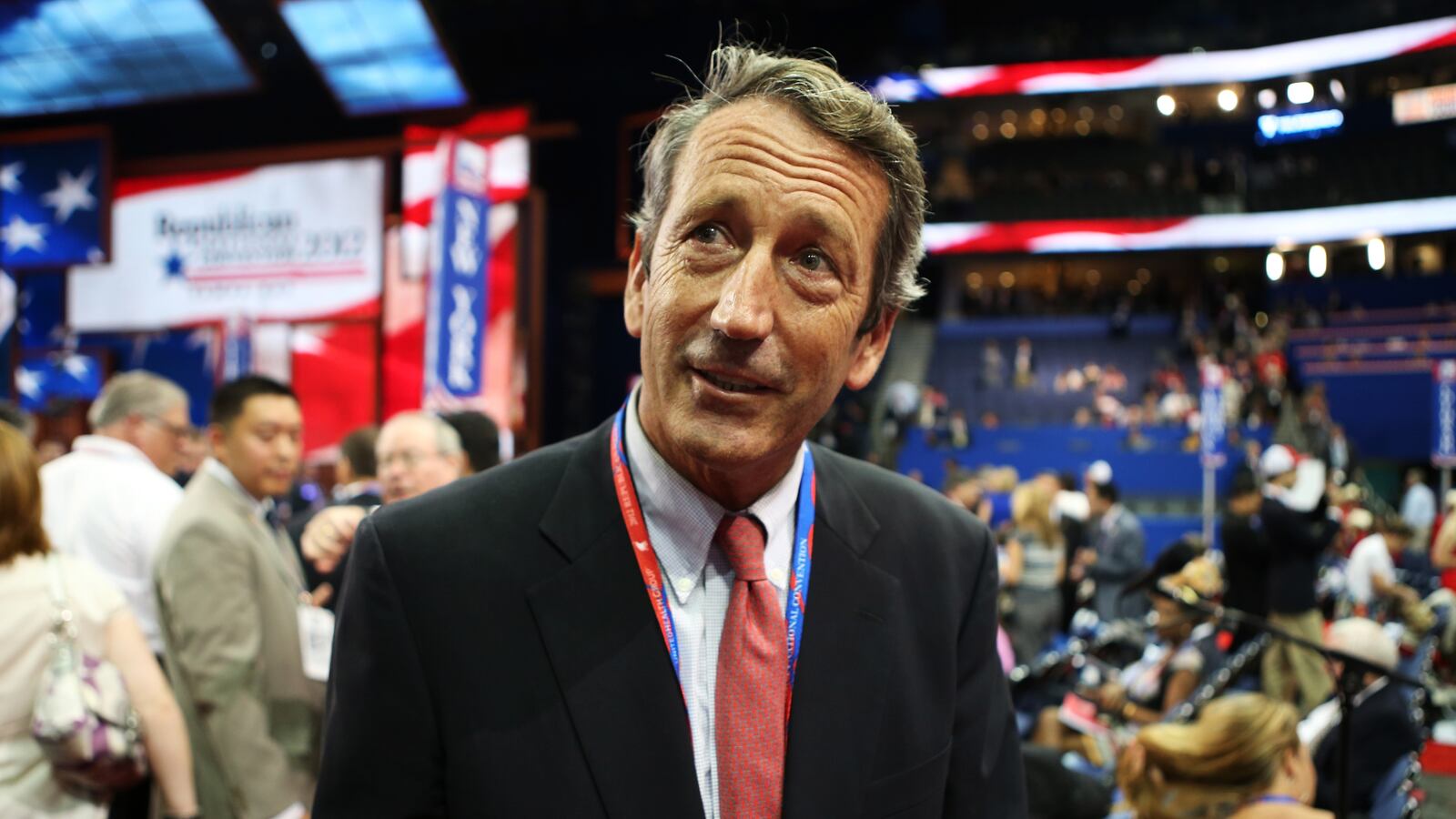

It’s official: Mark Sanford is running for his old congressional seat in South Carolina.

The former governor, who ended his second term in disgrace after admitting to an extramarital affair with an Argentine woman he described as his “soulmate,” had previously been considered a leading potential contender for the 2012 GOP nomination before the scandal consumed those ambitions.

But suddenly Sanford is back. Among many locals, he is considered the frontrunner in the special election to fill the congressional seat held by Tim Scott before he was appointed to the U.S. Senate—an unusual degree of turnover in a state where Fritz Hollings served as junior senator to Strom Thurmond for 36 years.

“Life has a lot of different strange twists and turns, as I’ve come to understand firsthand,” Sanford said over the phone from South Carolina on Wednesday, when he announced his run. “Lo and behold, a U.S. senator resigns—that happens so infrequently—and then the governor appoints the congressman from the First District, which I used to represent. When that happened, the phones lines lit up. I started getting these phone calls and emails, and the intensity told me something was going on ... Tom Davis [a friend and South Carolina legislator] said, ‘Mark, you’ve to do this thing. You were talking about debt and deficit spending decades ago.’”

This is true. Sanford was Tea Party before there was a Tea Party—and before the brand was damaged by Michele Bachmann–like zealots. A charter member of the 1994 Republican revolution, Sanford was a sometimes lonely voice arguing for Social Security reform at a time when the public treasury was piling high with surpluses in the late 1990s. He was never afraid to take hold of that politically perilous third rail and talk about existential issues facing the United States.

But Sanford was also a modernizer, committed to a new Republican Party that was fiscally conservative but not dogmatic on matters of faith, despite representing a state often considered a bastion of the religious right. He exhibited a rare and welcome soft libertarian streak amid Southern conservatism. He criticized pork-laden bills that were backed by fellow Republicans. His Lowcountry district—where my parents live—has always been a bit more relaxed and live and let live, inspiring the title of a glowing Economist profile from 1998, “Mark Sanford, Surfboarding Revolutionary.”

Before the scandal, Sanford was known as an unusually honest and self-effacing politician, and he says he understands the obligation to rebuild trust from the ground up. Nothing is assumed. He peppers his conversation with phrases like “If I’m afforded this second chance,” acknowledging the need to admit to his mistakes if he ever hopes to move on.

“I’m a sinner,” he said simply. “If you live long enough, you’re gonna fail at something. I failed very publicly. But now we will see if the voters will support someone who has worked on the issues for a long time.”

One of his first conversations before he decided to run again was with his ex-wife, Jenny Sanford, who remains popular across the state and had been publicly mentioned as a possible Senate nominee and even a congressional candidate. He drove out to the family’s beach house to broach the subject: “I sat down with her on the porch and said, ‘If you have any thoughts about running for this, then I’m out, because I can’t think of anything more disastrous than for a husband and wife to run against each other,’” he said. “I also told my boys that I wouldn’t run if they didn’t want me to run.” Having received the family’s OK, the once and future candidate was off to the races.

Rarely has a candidate faced such high stakes in a congressional race—nothing less than a chance at both personal and public redemption. “In my case, for better or worse, they are inextricably entwined,” Sanford said. “I failed very publicly, and yet what I learned in the wake of that failure is that there is a tremendous reservoir of God’s grace on a personal level and citizens’ grace on the public level. I’ve had people say to me, ‘I’m not going to judge you on your worst day or your best day—I’m going to judge you on what you’ve been doing in this community for decades’ ... So there will be a degree of both personal and public redemption if I make it.”

The subject of his fiancée is not one Sanford offers or hides. The irony is that he always was a politician who kept the separation of church and state clearly prioritized in his family life. “Prior to 2009, you probably got one sentence from me about my private life,” he said. “And then you got this excruciating and embarrassing chapter in my private life, with these very private and personal emails coming to the surface.” But now those storms have passed, and something like peace has reemerged. “Her name is Belen,” he said with matter-of-fact, protective pride. “I love her, and I’m engaged to her, and I’m going to marry her.”

It’s safe to say Mark Sanford hadn’t previously been busy plotting a return to politics. He’d been more or less happy back in business with a sideline as a Fox News commentator. Unlike a Bill Clinton, he never seemed to crave the game. This unexpected return to politics seems like half a happy accident and half a cold-water test of character—both for himself and his former and perhaps future constituents.

A week is a long time in politics, and nothing is assured in the full-contact world of South Carolina campaigns. But Sanford’s chances are buoyed by a healthy war chest left over from past campaigns and a high name ID in an otherwise crowded special-election field. Among the other candidates are the sons of Ted Turner and Strom Thurmond, as well as an ambitious former state senator, John Kuhn. The first round special election is scheduled for March 19, and unless a mathematically unlikely 50 percent threshold is reached by any one candidate, a run-off will be in May.

Nationally, Sanford’s name might still be faintly tainted, but all politics is local, and at least on policy he can credibly claim to be steadfast and true. “I hope we’ll be able to focus on the issues that I’ve be consistently tried to push in terms of fiscal responsibility and limited government,” he said with clarity. “I’m not running against anyone in this campaign. I’m running for the ideas that I’ve long believed in and I’ve got a real track record on—and let the chips fall where they may.”