When asked what movie or television show first made her fall in love with the industry she’s now covered for three decades, Burn It Down author Maureen Ryan first looked back on a warm memory of sitting down to watch The X-Files with friends after an exhausting moving day in Chicago in the ’90s.

Ryan recalled that she and her friends were “just completely drawn in by this very strange, surreal world that they had created. I remember very specifically being like, ‘Oh, I need to know more about that,’” she told The Daily Beast in a recent interview.

But she didn’t stop there—the veteran critic, reporter, and self-described “huge sci-fi nerd” also went on to profess her love for Battlestar Galactica, written by some of the same creative wizards who’d concocted her favorite material in Star Trek: Deep Space Nine. And then there was Deadwood, and The Shield.

“There’s so many shows in the early aughts, especially, that were reinventing what I thought TV was, and it was so exciting,” Ryan said. “And it’s not that I didn’t love film… I’m just very much a relationship person.”

Spend a few minutes with Ryan, and it becomes clear she could do this for hours. As the full title of her book suggests, however, her perspective on the industry she covers is not nearly as romantic as her relationship with its output.

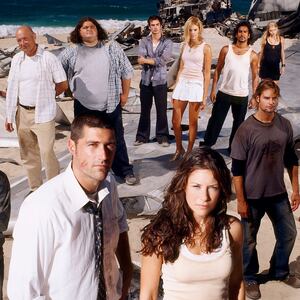

Burn It Down: Power, Complicity, and a Call for Change in Hollywood chronicles the systemic abuses that underpin the industry. Dishy behind-the-scenes dispatches about popular TV series including Lost, Saturday Night Live, and Sleepy Hollow give the deeply reported book its fire, but Ryan tempers that flame with a call to improve the system—and some solid suggestions as to how that might be achieved.

Speaking with The Daily Beast, the author discussed how this industry that’s created so many beautiful things got to be so ugly—and how a personally traumatizing experience at an industry event almost became her “supervillain origin story.”

Author Maureen Ryan outside her west suburban home on May 30, 2023.

Shanna Madison/Chicago Tribune/Tribune News Service via Getty Images“If you’ve had a career in Hollywood for longer than five minutes, you’ve probably been in a very unprofessional and nightmarish situation,” Ryan said. “A big part of [writing Burn It Down] for me was, all right, let’s talk to people who are trying to make change. Because if it was just a bunch of takedowns, what I’m leaving the reader with is hopelessness.”

The following conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

If you had to describe the pathology that lies at the center of all of Hollywood’s problems, how would you sum that up? And how did you think about how you wanted to organize all of that in book form?

I’m very proud of myself because I do like to talk—and I sometimes talk on at length—but I can sum up what my book is about, and all the disparate things that it touches on, in one word. And that word is exploitation. Michael Schulman has a wonderful book out right now called Oscar Wars, in which he delves into why the Oscars came about. It was partly because there were a ton of scandals around Hollywood, and partly because they wanted to forestall unions being formed in Hollywood, in Los Angeles. And it worked for a while. I think that that’s really a wonderful analogy, because that was almost 100 years ago. The two things that Hollywood wants is a lot of cheap, disposable cannon fodder.

Both on screen and behind the scenes.

The bedrock foundational principle of Hollywood was, “We can exploit the disposable people that we want to use up and toss aside.” And they can do that because there is this idea that it’s glamorous. I don’t want to be all doom-and-gloom and Debbie Downer about this at all, because there are people who have a wonderful time creating together, working together, imagining together, and making a decent living doing something they like. But the gatekeeping to get to that spot is incredible.

I have to tell you, I’m incredibly heartened by the response to my book. On every possible front, from people in the industry and outside the industry.

I was going to ask what it’s been like.

Over the past six years, especially, there’s been much more recognition that a job in Hollywood is just that—it’s a job... And in many ways, there are more hurdles, and more dangerous and more difficult things in that job than if you are a real estate agent in Chicago. Not to say that real estate agents don’t face their own problems, but people are much more open to the idea that a job in Hollywood is not necessarily glamorous—it’s possibly the opposite of that. So that’s the first thing.

And the second thing is an outgrowth of that, which is, people are recognizing the struggles of workers to be treated respectfully and compensated fairly across the board. Across industries, people are saying, “I will not put up with this.” Either they’re forming a union, or they’re having a walkout, or they’re going public with abuses. There are sort of eye-opening revelations about particular people or shows in the book, but what’s quite possibly more meaningful to me is that people understand that someone working on a streaming show is not all that different from someone driving for Uber, or someone working in a warehouse, or someone working in this gig economy that we’re all in.

People picket outside of Paramount Pictures on the first day of the Hollywood writers strike on May 2, 2023 in Los Angeles.

David McNew/Getty ImagesI had been wondering how you chose which industry figures to include in your book. And to the extent that you can say, were there any that you’d hoped to include but couldn’t?

For the book, the selection criteria was this: How does this illustrate syndromes that are still going on today, right now? How does this illustrate dynamics that are very deeply rooted in the industry and still have an effect on the industry? It couldn’t just be this insane thing that happened on a show where there’s no wider implication—it’s not illuminating patterns and problems that still exist. One thing I will note is that Hollywood has voluntarily reformed before, and that was through the Hays Code. And that was, you know, on a lot of fronts, terrible. So these things are stuck, and they’ve been baked into the system for a long time.

[In Burn It Down] I felt like I want there to be some test cases that help illuminate what people are up against. I very much also didn’t want the book to be exploitative—just purely gossip or rehashing people’s trauma or painful situations without context. If you’ve had a career in Hollywood for longer than five minutes, you’ve probably been in a very unprofessional and nightmarish situation. A big part of it for me was, all right, let’s talk to people who are trying to make change. Because if it was just a bunch of takedowns, what I’m leaving the reader with is hopelessness.

Right, and you very much do avoid that. Was that also part of the reason that you spend Burn It Down’s final section laying out suggestions for a better way forward? How do you go about finding experts for something like that?

Well, honestly, that was really just calling a bunch of sources who I had talked to and gotten to know over the years… I kind of had a bunch of people in mind that I knew were really trying. I had seen evidence of that trying. The thing that people fall back on—and I say this a few times in the book, and I almost wish I’d said it more times because I could talk about this all day long—people in Hollywood have treated certain systems, elements, and behaviors as inevitable. They are not. The whole last third of the book is me saying, in so many words, in neon letters, “Here are people who were raised up in a system that said, ‘These negative things you’ve encountered are inevitable and unavoidable.’ These people avoided them. They not only avoided them, they are setting an example for their peers of how to avoid them.”

And so anyone who says, “Well, it has to be that way,” no. You’re choosing for it to be this way. Own the active decision you’ve made. And I’m not saying that people don’t make mistakes... But what I also don’t have time for is, some people get given an infinite number of chances and don’t change, or those around them accept some cosmetic nonsense as change.

This book threads a needle that can be hard to negotiate: the need to maintain relationships in the industry so people still actually pick up the phone when you call, and the simultaneous obligation to be truthful about them. What is it like when you’re having tough conversations like the one you had with Damon Lindelof, whom you’ve known for years, about the behind-the-scenes chaos at Lost?

I don’t enjoy excavating something very difficult, and it can be very hard, as it was in my interview with Jeff Garlin in 2021, just to keep the interview on track sometimes—to be really focused on what I need to accomplish. But I take inspiration from people I have worked with on stories—and this is from an assistant, to the No. 1 actor on the call sheet, to executives, to mid-level people in the industry. So many people have allowed me to tell their stories. They were taking a huge risk. And they took that risk because they believed in something greater than themselves.

I’ll never forget my conversation with Lucas Till [for an exposé about former CBS showrunner Peter Lenkov]… He said, “This is my breaking point. I can’t stand how this colleague is being treated. It’s not OK.” If people just want to write off Hollywood, I mean, I can’t stop you from doing that. But what’s heartening to me is how many times I have heard that sentiment from people that, “Look, I’m really nervous to talk to you. I’m really scared. I don’t know what will happen to my career. But I want to have my coworker’s back, and I absolutely corroborate what she said. I was there, and I heard it too.”

The Damon interview was difficult, but you know, I’m at the point now in my life where I unfortunately have many, many difficult conversations with people. And the conversations that I also had with people who worked on Lost, who worked on Sleepy Hollow, those were so indelibly etched on my memory that I felt like I wouldn’t be able to live with myself if I didn’t do what I think a reporter can do… which is ask those questions that hopefully lead to some kind of, if not catharsis, if not accountability, then at least excavation. To me, that larger purpose is really meaningful, and talking to the sources for my book—this is going to sound corny, but they’re just inspiring people. They really are.

Has anyone mentioned in the book responded angrily? I guess you probably wouldn’t be able to tell me if Lorne Michaels has yelled at you.

Honestly, Laura, I will tell you for free, I was worried about that. Like, oh gosh, what will happen? No one at all… Maybe the people who are mad are just keeping quiet—in which case, thank you… The response from people who I spoke to for the book is either silence, or, in many cases, the sources that I spoke to have been really kind and positive.

I hope this does not sound self-aggrandizing, but one of the things I’ve witnessed in my work, over and over again… I’ve witnessed people experience catharsis. Because I really, really think that in this life, what people want is to feel seen and feel heard. And the weird thing about this creative industry of Hollywood is that quite often, the people within it, their voices are suppressed… The more you allow people to feel that they are sane, they’re not losing their minds, and what they’re asking for is correct and what they went through was wrong—the more you can validate that in a responsible, thorough, contextualized way, the more they feel empowered to act. And hopefully, the more these companies feel like they should be proactive about this stuff.

The problems in Hollywood go beyond labor exploitation as well. You’ve written in your book and in Variety about being sexually assaulted at an industry event. To the extent that you feel comfortable, I wondered if you could lay out what it’s like not only to endure something like that, but to do so in an environment that very much does not like it when you then go and talk about it.

It really nearly drove me out of the industry. It really made me question a lot of things… You know, even the tougher stories that I’d done up to that point were all about, I want this industry to be better so that the good people and the good projects in it can thrive. I had a very up-close and personal encounter with a situation that a lot of people face, which is, I nearly left the industry because I just didn’t want to have anything to do with it after that. It very much kind of broke my worldview about the industry, and it really psychologically affected me a lot. I didn’t know whether I wanted to continue, but I did report the person. I had a hugely negative, re-traumatizing experience doing that. And that’s what people don’t understand about being a survivor, is that so many things re-traumatize you along the way.

I understood it in a different way—the fact that the companies are not helpful when you’re trying to report these things, and it’s really traumatizing, and it’s incredibly demeaning and demoralizing and humiliating. So when MeToo broke open, I went into that with my sort of default mindset—you know, that anyone trying to enact change is going to encounter people who want to break them, humiliate them, gaslight them, abuse them further. I kind of knew the gamut of how it works.

I’m glad you asked about that. Because I do think that whenever this conversation comes up—like, should survivors be allowed to write about X or Y? I’m like, if someone’s served in the Marine Corps, you wouldn’t say they couldn’t cover the Pentagon. I don’t understand why this is the one where people get hung up. I don’t want this to be a requirement for anyone doing this work at all. I don’t want it to happen to anyone. But it gave me an understanding of how to work with survivors. I do think the work that I’ve done in the past six, seven years wouldn’t have happened had I not had that brutal education. It was really rough. But when MeToo happened, I don’t know, I think it’s almost my supervillain origin story. I’m like, what can you do to me?

That’s how you became the Joker.

It’s how I became the Joker! Yeah, too bad. So sad.

One of my favorite anecdotes in the book is about Renée Zellweger making it a point to check on an assistant who’d spilled coffee on himself before a big meeting. Are there any other celebrities whose do-gooding has been particularly memorable?

Oh, wow, that’s a good one. I hope I’m not proven wrong about this. I personally have not heard anything bad about Drew Carey. I know that he’s covering people’s lunch bills, or their dinners in a certain diner in L.A., who are on strike… It’s like, you know what, I have money, I’m gonna give money to people who are striking because I want to be your dude. And come on, it’s cool. Like, if you’re gonna be a rich, famous person and you can do that, why not do that?