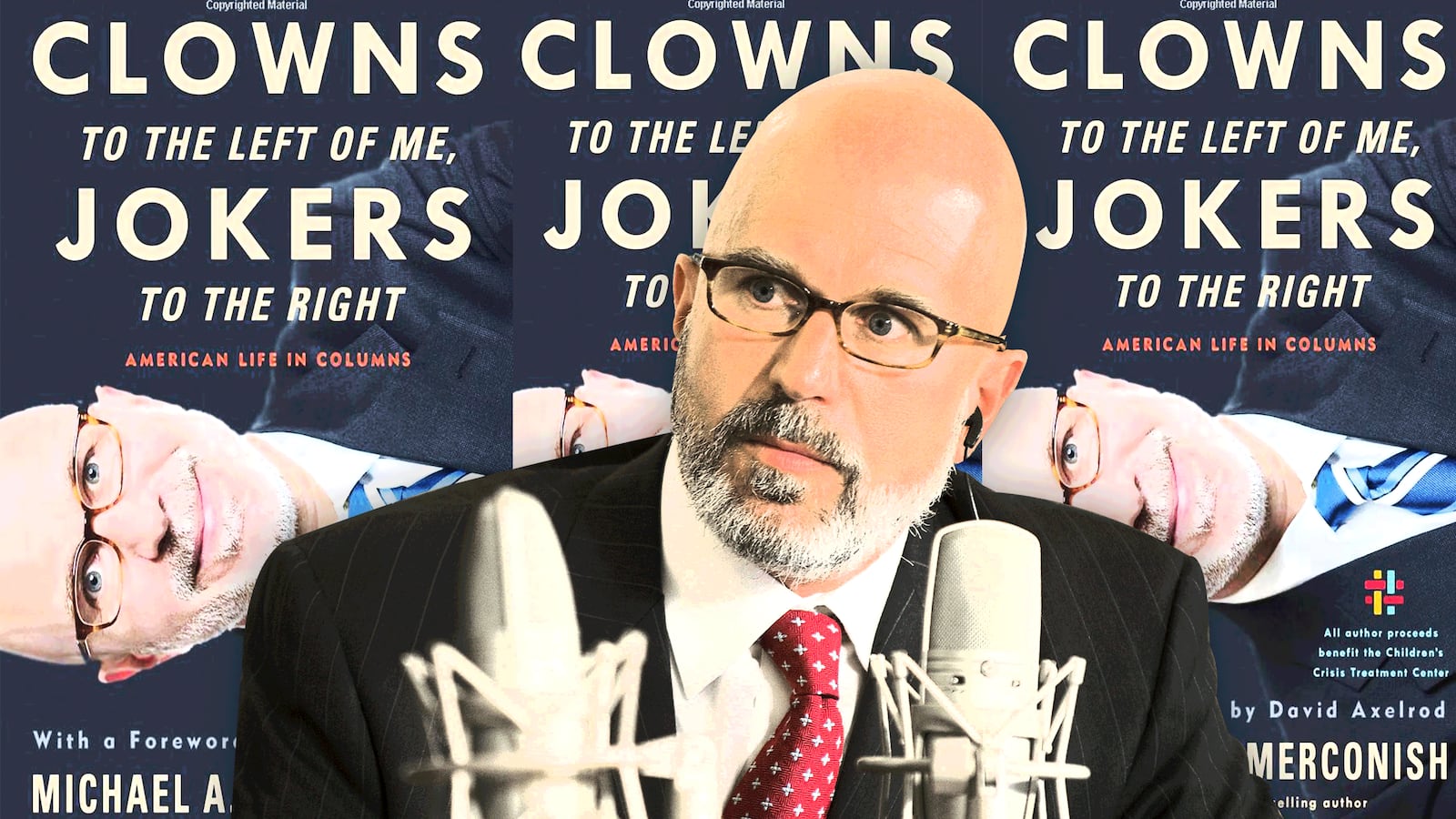

In our polarized world of “cable carnival shoutfest” and intransigent partisanship, Michael Smerconish is an increasingly exotic and refreshing voice. A prominent Sirius XM radio and CNN television host, he has been a regular contributor to the Daily News from November 2001 until 2007 and after that, a Sunday Philadelphia Inquirer newspaper columnist until the present day. Clowns to the Left of Me, Jokers to the Right is Smerconish’s seventh book. It brings together a representative selection from the 1,047 columns he has written over the past 17 years that cover politics, profiles, life, and miscellanea.

A good number of these columns have stood the test of time. A few others Smerconish probably wishes he had never written. The columns he has included in this book are reprinted here as they appeared in the original form, with an afterword from the author that provides, in his own words, “an update on facts and feelings.” They make for enjoyable reading and remind us that journalism properly practiced requires a good deal of nerve, honesty, and insight, along with openness to dialogue and the determination not to live in a bubble.

Smerconish’s columns offer a representative slice of 21st century American life with all its ups and down, real heroes, and controversial characters. He writes with plain words and communicates his feelings in a straightforward manner. We get to meet here not only the likes of David Duke and Rush Limbaugh but also the sober voices of Arlen Specter, Tim Russert, and Jack Kemp. An inveterate admirer of Ronald Reagan, who he met in his youth, Smerconish does not shy away from applauding, when necessary, the rhetorical skills of President Obama. Nor does he avoid taking to task one of the politicians he respects, Senator John McCain, for failing to put forth an inspiring vision for the country in 2008.

Osama bin Laden and Fidel Castro (whom Smerconish met in Havana in 2002) also make appearances, along with Pink Floyd’s Roger Waters, a radical critic from the left, and the former President of Pakistan, Perez Musharaf, whom Smerconish invited to watch elections in Pennsylvania. Other columns showcase positive celebrities such as Joe Frazier and Jim Beasley, a famous Philadelphia trial lawyer, as well as lesser-known models like Harold Carmichael, a Philadelphia Eagle wide receiver. Smerconish also pays due respect to military heroes and often invisible officers who sacrifice their lives and energy to keep us all safe at home. He is fascinated by examples of courage and real stories that give an adequate image of the virtues of the country to which his family emigrated decades ago from Montenegro.

As a journalist who spends a great deal of time talking to people every week, Smerconish is aware that many of us wear blinders on divisive topics. He is determined to challenge us to revisit the grounds of our beliefs. When interviewing his guests, his style is fair and direct, the opposite of a lackey or biased critic. Smerconish has tackled controversial topics from gay rights, sexual assaults on campus, and legalizing prostitution to racial profiling in the airline industry and political correctness. To his credit, he has approached complex cases with a sense of humor and detachment that has prevented him from being self-righteous or embracing false certainties.

On some of these issues, Smerconish has been prescient and on the mark. On gay rights, for example, he parted company with his fellow Republicans who opposed them. He expressed reservations about the decision to invade Iraq in 2003, calling instead for prudence. And he stood firmly for respecting the rule of law in the infamous case of the Duke lacrosse team from a decade ago. On other topics, however, Smerconish’s initial judgment was off the mark, which explains why he felt compelled to make a few mea culpas. It was arguably unwise to side, as it were, with Bill Cosby when the first accusations against him surfaced more than a decade ago. Smerconish’s most recent oversight has been his failure to anticipate and understand the rise of Trumpism (he was hardly alone in this regard!).

One of the most important lessons of the book is the urgency to burst the bubbles in which we live and the need to think independently without banners, as much as we can. Nonetheless, the costs of maintaining one’s political independence are very high in our climate today. Smerconish is aware of how difficult it is for journalists who aspire to be in the center to be impartial and unbiased. They risk being attacked from both aisles and might end up forgotten or despised in a political no-man’s land.

A second lesson has to do with the importance of political moderation. To those dissatisfied with our current political landscape, Smerconish offers a nuanced defense of political eclecticism and trimming. I am not sure he would accept the label moderate, but I believe that he fully deserves honorary membership in the select club of moderates. On some issues, Smerconish thinks like a conservative, on others like a liberal; he is simultaneously optimistic in some regards, and pessimistic in others. If a few decades ago he had a tendency to see the world in black and white, he has learned to explore and appreciate its many shades of gray. Now he can say, with Adam Michnik, “Gray, too, is beautiful!”

The shift away from the Republican camp into the camp of the politically homeless ones who “don’t stack up neatly in any ideological box” illustrates this point. In a column originally published in February 2010, Smerconish candidly admitted, “I am not sure if I left the Republican Party or the party left me.” He acknowledged that he no longer felt comfortable in a party obsessed with ideological purity that had come to use litmus tests and see the political scene divided between agents of good and evil. He left the party because he valued his independence and was no longer motivated by ideology.

By refusing to serve a doctrinaire, ideologically driven agenda, Smerconish’s columns and broadcasts are unlikely to be loved by purists on either side of the aisle. Elizabeth Warren refused to speak to him, and Trump’s supporters hold him in low esteem. Smerconish’s desire to think and act like an independent journalist requires a combination of audacity and moderation. By embracing a bold form of moderation, he risks being added to an endangered-species list.

Yet, the situation was different several decades ago. During the Reagan era, for example, moderates amounted to about 60 percent of the Senate. Since then, they have been the victims of money, ruthless primaries, and gerrymandering. In the media, they have been ridiculed or silenced. As a result, “the elected middle has vanished” and the center has become a lonely place in American politics today. Following partisan signals, sometimes fueled by fake news and apocalyptic rhetoric, voters in both parties tend to reward ideological purity over compromise. They prefer politicians who reject conciliatory tones and present themselves as the opposite of wishy-washy, a pejorative label reserved for moderates, condemned for their eclecticism and flexibility.

It is time to change all that, Smerconish argues, beginning with journalism. Journalists must relearn the art of civility so that they can have once again substantive dialogue rather than a series of monologues of the deaf. In turn, politicians should rediscover the art of compromise so that gridlock gives way to effective political deal-making.

The good news is that we do not lack models in this regard. Two columns included in Smerconish’s book offer moving tributes to the late Tim Russert and Arlen Specter, both role-models of civility and responsibility in his view. Smerconish admires Russert for creating “a forum where clear differences would emerge, but they would be expressed without shouting or crosstalk.” Impartial but firm, Russert was always willing to listen and reflect; if he appeared humble and down-to-earth, he was never condescending or hypocritical.

In Arlen Specter, Smerconish appreciates the combination of courtesy, civility, realism, and humor that made him the moderate who put the country before his party in times of crisis. Specter’s change of party in 2009 after his vote for Obama’s stimulus package was a telling example of the realism of moderation; his subsequent fate, a telling reminder of the dangers of moderation.

These are indeed good examples to follow in our age of ideological intransigence and cacophony. If we want to avoid coming apart because of our differences and discord, we need to build bridges and cultivate dialogue with our opponents and critics. We should be grateful then to Michael Smerconish for standing up for a type of journalism that elegantly blends courtesy, dialogue, and responsibility. As long as voices like his are still heard, hope is not entirely lost.