LONDON — On a recent afternoon the Open Russia Foundation, which basically represents the brains and money behind the Russian opposition, held an event at its headquarters on Hanover Square in London. And the predictions for Russia’s future seemed to grow darker by the minute.

Two Russian scientists, Yelena Lukyanova from Moscow’s Higher School of Economics and Dr. Vladimir Pastukhov from Oxford’s St. Antony’s College exchanged speculative arguments about the chance Russia could one day fall apart. How much longer will President Vladimir Putin hold on? Participants wondered. And what will become of Russia after he’s gone?

On the back row of the rather thin audience, the foundation’s sponsor, exiled Russian tycoon Mikhail Khodorkovksy—in torn jeans—was busy reading an e-book. Only once did the host of the event peer up through his spectacles to glance at the event’s participants.

The master of his little empire on Hanover Square, Khodorkovsky has spent years in Russian jails and, most recently, was charged by Moscow with the 1998 murder of Neteyugansk mayor Vladimir Petukhov. In 2010 Putin said about Khodorkovsky, “This man has blood on his hands.”

He’s not going back there any time soon. But he who formerly was the richest man in Russia has a long-term goal: to outlive Putin while preparing his countrymen for major reforms.

“I plan to return to the country; I will come back as soon as the regime begins to fall apart,” Khodorkovsky told The Daily Beast in an exclusive interview last week. “And now I am doing a lot, everything I can, to arrange it so that when this regime begins to fall, the collapse happens in a different way, so the damaging mistakes made in the early ’90s are not repeated.”

It was the chaos of the crumbling Soviet empire and the collapsed Russian economy 20 years ago that opened the door for Putin’s brand of order and national pride.

The most recent survey by the Levada Center shows that Khodorkovsky, albeit in exile, is the most famous opposition figure in Russia: 45 percent of Russians know his name. About the same percentage, 47 percent of the population, approved of Putin’s decision to let Khodorkovsky out of jail, where he spent 10 years for tax evasion, fraud, and embezzlement.

That decade of incarceration gave him plenty of time to think of Russia’s future. And he feels like he can wait another 10 years, if that is what it takes. Members of his team talk about Khodorkovsky as a thinker with great endurance, “a long breath.”

It would seem likely that Putin, with his current, vast public support and lack of internal competition, will easily win presidential elections in 2018 to remain Russia’s president for six more years, until 2024. By then, Khodorkovsky would be 60 years old and Putin would be 72.

But the delay and uncertainty do not seem to disturb Khodorkovsky. “I think there is a chance that his system will be finished sooner than in 10 years,” Khodorkovsky told The Daily Beast. “This is a very unstable situation, as Putin’s circle begins to think, now, what will be left after Putin? The model that he is constructing now is not able to live long—in 10 years, he will have a crisis of loyalty, when he is over 70 years old and his bureaucrats will be only 40 years old.”

While still in prison, Khodorkovsky published thoughtful, well-researched articles in independent newspapers, giving thousands of his countrymen in the most remote corners of the country hope that he would change their lives for the better.

Those expectations are what keep him pushing for change, said Khodorkovsky, even though he knows he may be vulnerable for promising more than he can deliver at this point.

“As soon as a person begins to act, immediately at least half of the people who had been waiting for him begin to demonstrate how displeased they are with what he is doing,” said Khodorkovsky.

His intuition about public support was right. At least for now, Russians do not see him as a future president. Even the most open leaders of Russian civil society have felt frustrated about Khodorkovsky’s words and work in the past two years. His Open Russia team, with rare exceptions, is blamed for being greedy, cynical, and making money off the former tycoon.

“I stopped being interested in what Khodorkovsky and especially his employees do; they are even more useless for Russia, than the deputies in the Duma,” said Anton Krasovsky, a civil activist leader from the Stop AIDS movement. “Unfortunately, I thought he would be our breakthrough but it turned out that his foundation did not make much difference—that is a major disappointment.”

An activist from Russia Behind Bars, Olga Romanenko, believed Khodorvsky was smarter than Putin but “also an imperialist with a very Soviet mindset.”

For Chechen civil society, Khodorkovsky’s position on the independence of Northern Caucuses republics from Russia was unacceptable. A Chechen human rights defender, Raisa Borshchigova, told The Daily Beast that she was once a big fan, and read all of Khodorkovskiy’s correspondence from prison with Russian novelists.

“I thought of him as a Russian Mandela, but he made a deal with Putin to come out of jail, then said that he would fight against us Chechens, if necessary—he is no different from Putin who bombed Chechen civilians,” Borshchigova said.

Khodokovsky is no longer among the world’s extraordinarily wealthy people. He was once worth an estimated $15 billion. According to the recent analysis by Forbes he is today “an ordinary multi-millionaire” worth $100 million to $250 million.

He said he’s not looking for revenge, after the Kremlin took him away from his four children for so many years. Instead he deplored the Kremlin’s abusive pressure on civil society as a whole. On hearing recent news about the beatings of Russian and Scandinavian reporters near Chechnya, Khodorkovsky closed his eyes and repeated several times: “This is a catastrophe.”

Khodorkovsky looks back to the times when his oil company, Yukos, and other successful Russian businesses pumped billions of dollars into the Russian economy, enough to rebuild the country’s infrastructure.

“I feel most sorry, that at the moment back in 2003, instead of choosing transparency, industrialization of Russian economy, and its westernization, Putin got scared and chose his own unchangeable power with corruption, imperialistic capitalism, monopolized capitalism.

“We got $2 to $3 trillion dollars for the country. Where did they spend it? Instead of creating at least 10 solidly developed cities—they did not finish Peter, Krasnodar, Yekaterinburg—they flushed the money down the toilet.”

At his Hanover Square headquarters, Putin’s critic has created new mechanisms to challenge the current Russia’s leaders. “This regime has done a lot of bad things; there would have to be court trials with all the necessary evidence presented,” he said. “I am against persecutions. Our history has seen enough of that. But an independent court should find out whether Putin personally ordered Litvinenko killed or not, or if he personally ordered to shoot at peaceful people in Ukraine.” (Alexandr Litvinenko, a former intelligence operative who turned on Putin, was poisoned in London with a rare radioactive isotope.)

“The redrawing of internal borders could be discussed later, Crimea and Northern Caucuses could be discussed later,” he added.

At times Khodorkovsky spoke in his usual self-confident, top-manager tone, as if he was once again an important decision maker in Russia. “We’ll have a problem with people who really committed crimes, as there are thousands of them,” he said. “We would not be able to put all of them in the dock, so we would offer them the chance to sign an amnesty act stipulating conditions of depriving their rights to occupy state positions and obliging them to return all property.”

How to turn Russian society from apathy to social awareness, from accepting illegitimate institutions and rules to a society demanding its rights? That is Khodorkovsky’s favorite topic these days: making Russians believe that they run the state.

“My key idea, is that we break down the notion people have that the state controls them,” he said, suggesting, “We should take the income for natural resources and give it to people, from Individual pension accounts, the way they do it in Norway.”

Everybody, both in Russia and on the West, expected that sooner or later there would be a Vaclav Havel in Moscow, a quiet voice of reason and peace with whom the West would find common language.

Preaching from his London office and traveling around to international conferences, Khodorkovsky explains to European and American politicians, those who still doubted, that they would never manage to agree with Putin, because he has a “police mentality.”

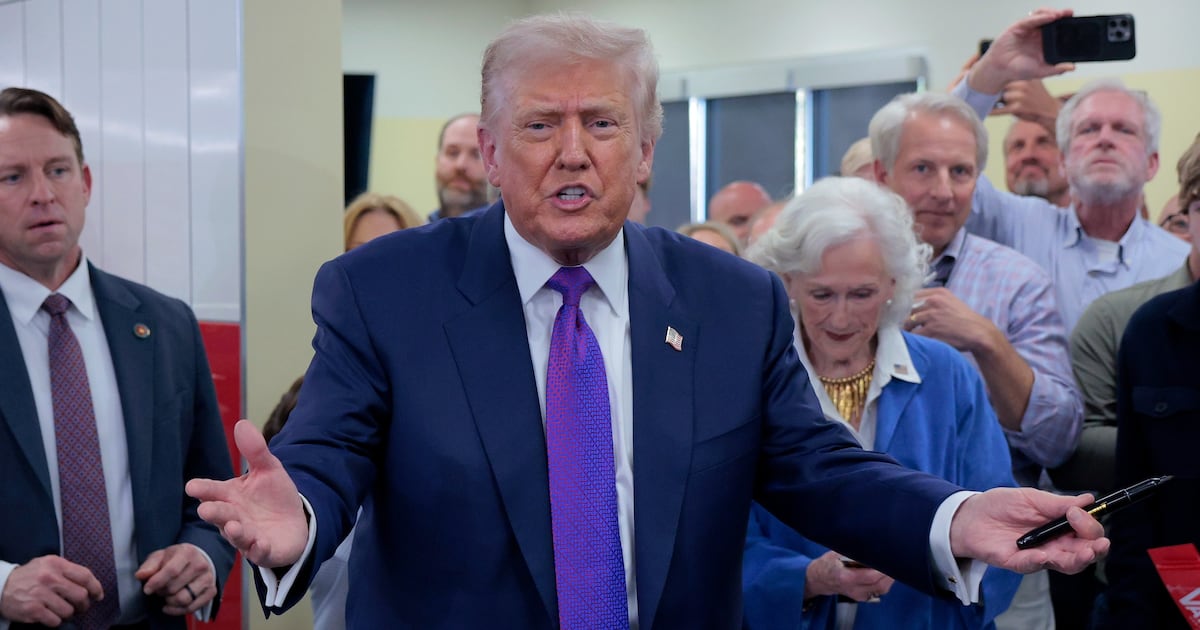

Alluding to the bluster and bullying of U.S. presidential candidate Donald Trump, Khodorkovsky said, “Even if somebody like Trump makes a deal with Putin, something will go wrong.”

Interpreting Putin to the West is one more role Khodorkovsky sees for himself as patiently, but persistently, he waits for the end of Putin’s role.

Editor’s note: an earlier version of this piece mistakenly quoted Khodorkovsky as saying he was against prosecutions rather than against persecutions. The Daily Beast regrets this error.