This is the latest in our twice-monthly series on underrated destinations, It's Still a Big World.

The desert night was as black as pitch. The car’s headlights weren’t working properly and I could barely see three feet ahead of me. For all I knew I might run into a wandering Nubian ibex, an Arabian wolf, or an endangered Arabian leopard. To make matters worse, the car rental company in Tel Aviv had rented me a defective cellphone, and despite continuously charging it the battery had died—again—an hour back. I’d meant to arrive at my accommodation in Mitzpe Ramon before sunset, but now it was past 9 p.m. and I was lost somewhere in the vastness of Israel’s sparsely populated Negev Desert with no navigation system. I hoped I wouldn’t topple the car straight into the Ramon crater.

"Ramon Crater"

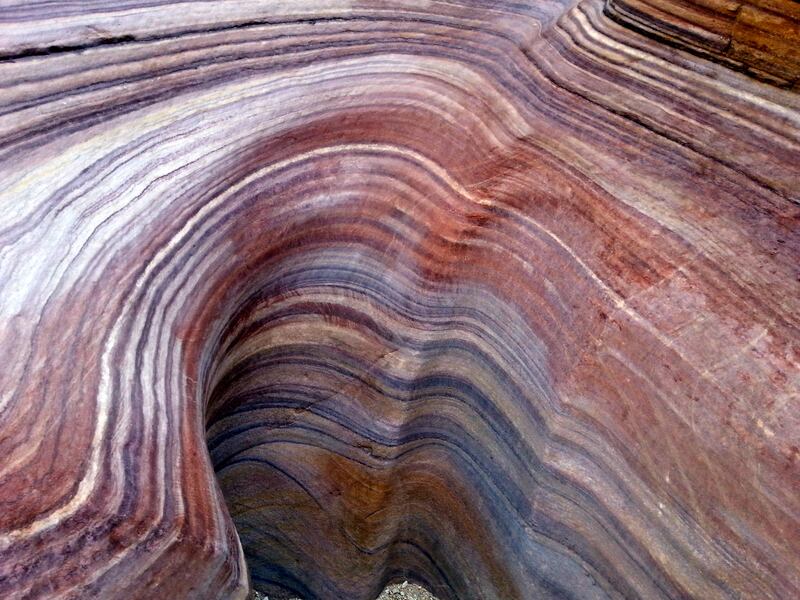

Elizabeth WarkentinWhen I finally stood on the rim of the crater the next day, I was wowed by this surreal geological formation. Often referred to as “Israel’s Grand Canyon”, Mitzpe Ramon, mitzpe meaning lookout, is situated almost 3,000 feet above sea level. Below the lookout lies the makhtesh, Hebrew for crater. Like the Grand Canyon when seen from the rim, the 25 mile-long, up to six-mile-wide, and 650- to 1649-foot-deep bowl sometimes appears to have no horizon line, as if it were a picture you could walk into. With its lunar-like landscape of cotton ball white, peanut and caramel rock, coral pink- and cream-striated sandstone walls, and miniature mountain ranges rising off the desert floor, it’s the perfect movie stand-in for a fictional desert planet.

The word crater is actually a misleading term to describe what is in fact an erosion cirque. “When you speak about a crater you’re talking about one of two things,” says Itay Harary, founder of tour company Deep Desert Israel, as he crouched down in the sand to demonstrate with small chunks of limestone.

“Either a meteorite crashed into the earth and created an impact crater, or a volcano collapsed into its centre and then you have a volcanic crater. But we don’t have either of these. What we have is a unique geological phenomenon that occurs only in Israel… Millions of years ago before the continents split, this whole area, everywhere you look, used to be under an ocean. Tectonic plates pushed against each other and formed a small mountain that rose up above the surface of the ocean, forming an island. In time, wind and water eroded the island and a hole was hollowed out of the rock. It resembles a crater, but it’s not. This phenomenon is what we call ‘makhtesh’.”

"Rock striations"

Hen YannayAbout as remote as one can get in Israel, Mitzpe Ramon didn't even exist as a town until the 1960s. Founded as a workers’ camp in 1951 for the builders of a new North-South highway, Mitzpe initially attracted mainly North African and Romanian Jews who were hired to build roads. The town then dwindled for decades. Not so long ago, most Israelis wrote off Mitzpe Ramon as no more than a petrol stop and toilet break on the way to Eilat, 100 miles to the south.

More recently, however, the desert town on the edge of the crater has been growing, attracting city people from Tel Aviv and the more crowded North. Today there are approximately 5,000 residents, an eclectic mix of artists, entrepreneurs, wine-makers, hippies, outdoorsy types, and Orthodox Jews, all looking to escape the stresses of Israel’s more densely inhabited North.

One owner of a B&B just outside the town says he needed to get away from the problems of the North. He didn’t like being in the center of the country, near Jerusalem because the ancient city, for him, represents the worst of Israel. He prefers being in Mitzpe Ramon, where it’s quieter and more peaceful.

Hen Yannay, a professional photographer, educator and guide whom I met through Meijer, is originally from Tiberias, on the Sea of Galilee. Yannay moved to Mitzpe in 1994 to direct an artists' colony, eventually becoming involved with tourism in the region. His company, Desert Tours, offers hiking, jeep and photography tours of the crater. “Mitzpe is remote, very small and still raw,” says Yannay. “People, like myself, are trying in a way to run away from the chaos of Israel, from the conflicts. But since Mitzpe is also a challenge and not an escape room, so to speak, some stay, some leave. I love the desert, the peacefulness, the ever-changing landscape, and most of all the feeling that “anything is possible.”

"Rock climbing training for tourists in Ramon Crater"

Elizabeth WarkentinMitzpe Ramon also appeals to tourists who enjoy nature and the outdoors, hiking, walking, cycling, and jeep tours. And for the less risk averse, rappelling. From above, the makhtesh appears a bit flat, but down below there are mountains to climb and wadis to descend into, and the rappelling cliffs, when seen from below, look to be 90 degrees vertical.

More recently, Mitzpe has also made a name for itself as an astro-tourism destination. Since it’s so remote and so dry, the air is clear and there is no light pollution. In 2017 Mitzpe Ramon was designated a Night Sky Park by the International Dark Sky Association, the first in the Middle East. Bateva Desert Adventures gives stargazing tours. Participants sit on mats and mattresses around a campfire in the crater while owner and guide Nadav Silbert provides an overview of the stars, galaxies and solar system over mugs of tea and coffee. Afterwards guests get to look through huge professional telescopes to observe the night sky up close.

There were few stars visible when I visited in mid-August, but the sight of a giant tangerine moon rising above the dramatic landscape of the Makhtesh Ramon is definitely up there on the list of awe-inducing natural spectacles I’ve had the privilege of witnessing.

In the town proper, the epitome of nondescript, I was surprised by the diversity of people that are drawn to the area. When you walk into a restaurant or cafe, you’re just as likely to spot hikers and artists as you are Orthodox Jewish women wearing their hair tied back in pretty head scarves and speaking English with North American accents. I was impressed, too, by the number of artists’ workshops and interesting restaurant offerings for such a small town. One afternoon I wandered the Spice Route Quarter, a collection of interesting boutiques, artists’ ateliers, the Adama Dance Company, and restaurants and cafes situated in an erstwhile industrial area of repurposed hangars and warehouses.

I visited a soap factory and boutique, a visual arts gallery, a clothing factory, a vintage clothing shop, and the Lasha Bakery, celebrated in the Negev Highlands for its artisanal kosher breads, memulashas (savory pastries), cakes, and tarts. Later, I enjoyed a simple dinner at Habereh Pub, an atmospheric pub with live music, great food (good veggie options), imaginative cocktails and a relaxed atmosphere in which patrons are welcome to bring their dogs.

All of which—the motley crew of people and the hodgepodge of artistic and culinary options—imbue this desert town on the edge of a crater with a quirky, bohemian air of unreality.

On my last evening in Mitzpe Ramon I drove out 20 minutes from the town to Nana Winery. There I learned from owner Eran Raz that despite the Negev receiving only 100mm of rain per year, the Nabateans, the ancient desert nomads whose capital was located in Petra, had been making wine during the Hellenistic period. “We found remnants of their underground terrace irrigation systems,” said Eran, who goes by his nickname, Nana. “There was a big winery in Avdat,” an ancient hilltop city about 13 miles north.

"Entrance to Nana Winery"

Elizabeth WarkentinToday Raz and his fellow winemakers take advantage of modern drip irrigation technology that relies on underground computerized probes and long plastic tubes to gradually release water. Raz has been making wine for decades, but it had been a longtime dream of his to make wine in the Negev. Packing up his home in the fertile Galilee, he moved to the outskirts of Mitzpe Ramon, where, in 2007, he started growing grapes in the desert.

The early years were very challenging Raz told me, as we sat tasting wines in his glassed-in tasting room overlooking the vineyard, now suffused in red gold evening light. Soon after planting his first vines, he discovered that he’d “been planting on the main drug smuggling route between Egypt and Israel. The drug smugglers weren’t happy about this, so they’d send camels in to tear up my vines.” In time, however, once he and the neighboring winemakers formed an alliance to protect their property, they started attracting hundreds of people to their annual wine harvest festival. “And now,” he says proudly,” we have a new wine region in Israel.”

"Owner Eran Raz (Nana) in his vineyards with his dog"

Elizabeth Warkentin/Elizabeth WarkentinAs I sat with Raz swirling a glass of Syrah, I contemplated this. I mean, who would have thought the unforgivingly arid, underpopulated Negev Desert would ever become a wine destination? For that matter, who would have thought that a former laborers’ camp would recast itself as a tourist destination and a Nirvana for Israelis from the North? But thanks to the primordial beauty of its crater and its remote location in Israel’s more relaxed South, it has. And it awaits.