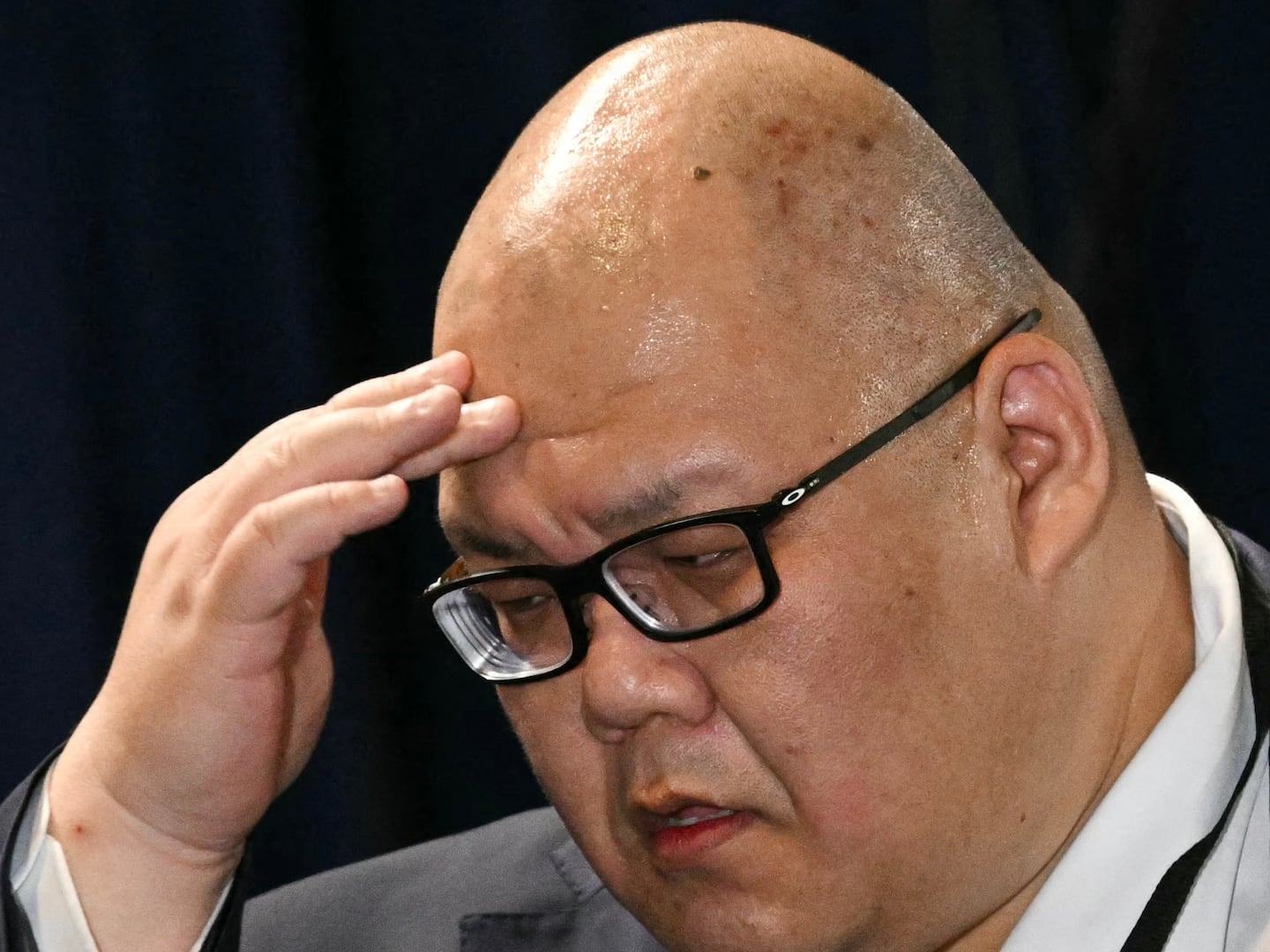

The Television Academy isn’t exactly known for its adventurous taste in Emmy contenders; it’s historically favored the familiar over the weird, the unconventional, or the bold. That’s why TV lovers rejoiced at this year’s Emmys love for the freshman season of Mr. Robot, USA’s mind-bending hacker drama from a creator new to TV, Sam Esmail.

Along with a nomination for the top prize, Outstanding Drama, the series earned nods for its mesmerizing lead actor Rami Malek, for Esmail in Outstanding Writing for a Drama, and for Outstanding Music, Casting, and Sound Mixing.

The radically ambitious story of antisocial computer genius Elliot Alderson, who joins an anarchic black hat group that destabilizes the world’s financial systems, concluded its first season with a devastating twist: the revelation that the group’s leader, Mr. Robot, was never real at all. Instead, he’s a figment of Elliot’s imagination, wearing the face of his dead father.

That twist’s flawless execution, along with a few tantalizingly unresolved plot threads, set expectations high for Season 2. But rather than replicate that first season’s winning formula, Esmail dove into a darker, more introspective examination of his tortured protagonist, now in self-imposed isolation at his mom’s house in New Jersey.

Except this time again, there was a twist.

(Warning: Spoilers for Mr. Robot Season 2 ahead.)

For seven episodes, viewers believed they were watching Elliot voluntarily “detox” from drugs, the internet, and the hacker group FSociety to keep his delusions of Mr. Robot at bay. But as “h4ndshake” revealed, Elliot, and thus we, had been immersed all season in yet another false reality. Elliot isn’t in New Jersey. He’s in prison. The woman we thought to be his mother is actually a prison guard. The diner he visits three times a day is a cafeteria.

And Elliot’s mind is still pitifully beyond his control. The progress he thought he’d made in reclaiming it was a lie. He’s still coping with the unbearableness of his everyday reality with illusions of faces, places, and things familiar from happier times.

This second shattering twist—one that more than a few internet sleuths deduced from Esmail’s visual language as early as the first episode—proved divisive among fans and critics. But Esmail insists that those premature visual hints were intentional (“We obviously telegraphed it and foreshadowed it as much as we could,” he says), and that dwelling on whether or not the latest plot twist came as a surprise is “missing the point.”

“I think it’s very impactful when a reveal does surprise you,” Esmail says. “It can get really exciting, but at the same time, a reveal always has to feel inevitable. Because if it’s shock with no basis in reality and no basis in what we’re invested in, then it can just feel arbitrary and like a trick.

“With us, we never wanted to do that,” he says, earnestly. “We wanted it to feel inevitable and to deepen how we’re seeing the story through Elliot’s eyes.”

Esmail talked to The Daily Beast about Mr. Robot’s four Emmy nominations, how its second season is just like The Karate Kid, the fan response to that prison twist, and the origins of this season’s dark, bloody ’90s sitcom opening.

Why did you choose the pilot, “0hellofriend,” for writing consideration?

I gotta be honest, my favorite part of any story is the beginning. Whether it’s a movie, a book, or a TV show, it’s the beginning. It’s the part where you start to reveal the world, reveal the characters, reveal the psychology. There is no limit to what you can create and what you can start. And as you go on, then you’re sort of limited by the world and the characters you set up. So the pilot was something that I think had that breath of fresh air that was the most fun to write.

Mr. Robot is still so bound to that pilot, even now in season two. You set up so many rules, themes, and relationships that still govern how the narrative is allowed to unfold. Is it gratifying to look back and know you managed to evade any plot holes?

It is. It’s tricky as you continue writing a TV show and things start to adapt. You start seeing chemistry on set and characters start to evolve and surprise you in different ways, but you always have this anchor that you set up in the beginning. And you had all these layers built up from the very get-go. The great and lucky thing about it for me is that those things blossomed, whereas sometimes I think there could have been a potential risk where they hamstrung the story and we could’ve ended up compromising the integrity of that pilot or the integrity of the set-up to go in a different direction. Or the story could have suffered because of all the hamstrings. In a way I got lucky with some of my guesswork in terms of what was really being set up in that pilot that took shape and blossomed with all the great performances from Rami and Portia [Doubleday, who plays Angela] and Carly [Chaikin, who plays Darlene]. And it turned out great for us.

You had a background in indie film before you made Mr. Robot—how do you feel like that helped make the first season what it is? People often described it as “cinematic.”

Well, I gotta be honest with you, for me in terms of television it probably wasn’t the best influence—or maybe it was, I don’t know. I don’t know any better in terms of television production. But what was good about it is that we were sort of free from trying to follow any formula or pattern for the episodic nature of the show. And that’s very clear going into the second season as well. ’Cause I think the tendency would be to reboot. To come up with a new Evil Corp and a new hack and a new season arc that puts our characters in an essentially similar situation and then go through the motions again. And because of the way my brain works in terms of feature filmmaking, because this was actually going to be a feature, we instead decided to go into what is the second act of the story, which is very, very different from the first season.

I always say it’s like comparing the second 30 minutes of a movie to the first 30 minutes. It’s obviously going to be very different, it’s a different phase of the storytelling and of the journey. With Elliot’s journey being the true north of the whole series, we just kept relying on that. I think for me, that’s really what helps a lot in terms of making the show. I look at it more as one piece as opposed to this—I don’t want to say repetition, but repeatable formula or structure that we have to return to every season. Another thing is that the filmmaking is another really important aspect of telling the story to me. I know that in television they traditionally say writer is king but for me, I think the filmmaking is equally important, if not more so.

That might be an accurate way to put it—comparing the first 30 minutes of a movie to the second. I think some viewers might still be adjusting to that with the second season, which started off with an extended lull in the action.

(Laughs.) You know it’s weird, one of my favorite movies growing up was The Karate Kid and one of my favorite sections of the movie is where Mr. Miyagi finally takes on Daniel Laruso as a student and the first thing he does is make him paint the fence and fan the floors and then wax the cars. And you’re watching this for maybe 15, 20 minutes and you’re like, wait a minute, I came here to watch a movie about karate. And then it all pays off and it’s great. It’s honestly my favorite part of the movie now. Sure, you’re gonna get to the ending where he does the flamingo kick and gets the girl and saves the day and all that. But I remember even as a kid being so fascinated by that [training] part because you get to learn so much about Daniel and Mr. Miyagi. He has that great speech about his wife and his backstory. And that to me is where we’re at in the Mr. Robot story.

That’s why there wasn’t a lot of hacking going on at first.

Obviously we hear the complaints and obviously it was intentional, but yeah, there wasn’t a lot of hacking in the beginning of the season. There was a time to stop and go through that introspection, that character-building to adapt to where Elliot’s gonna go and where he’s coming from. There’s that struggle to get to the next evolution of this character. The thing about Elliot at the end of the first season was he had this crazy realization about himself and we all felt that it would be dishonest to not address that—as if Elliot wouldn’t address that, in all the sloppy ways that a mentally ill person might, by self-medicating. It would be so dishonest if we were to ignore that or nip that in the bud in the first ten minutes of the first episode of the second season and have him go back to hacking. We also felt like what you do in that situation and how you navigate those waters was really compelling and interesting and something we hadn’t seen before. Much like that second act in The Karate Kid, where I had never seen karate taught like that before.

There was another big twist this season too, with the reveal that Elliot has been in prison since the end of season one—is there hesitation about writing in another twist like that again, knowing how quickly people figured it out this time?

I’ll kind of answer it two-fold. The first thing is that for me, every story has reveals and some are surprising, some are not. In every story, even if it’s not a mystery, you have expectations that the character is gonna go one way and then they go another. Or you might not have known something about that character and then it gets revealed by an action that surprises you, or doesn’t surprise you, or is something you expected them to do and then gets confirmed. For me, the word “twist” has a lot of negative connotation to it, right? It usually implies that you’re trying to fool the audience. It’s almost more like a magic trick in which you’re trying to do misdirection and the whole point is that you’re trying to get one over on them.

Whereas I think a “reveal” to me is a way to engage in a story where you learn something about the character in an interesting way—a way that you maybe wouldn’t have expected, and a way that hopefully would deepen your understanding of that character. So going into the second season, sure, we could have just had Elliot in prison, ’cause that’s where he was. But we thought that if we’re inside Elliot’s mind, with the way we set him up in the pilot—with his need to reprogram his life and his overactive imagination to cope by living an illusion—we actually felt that this would be a more accurate way of delivering the story through Elliot’s mind and his fractured point of view.

The second part about that is Elliot’s relationship to us and his unreliability. We left off at the end of last season with his animosity toward us [the audience, for keeping “secrets” from him] and a lot of mistrust. Those were the sort of two parts that led us into the second season storyline. And for me, again, when you watch a movie or read a book or whatever it is, if you anticipate something about the character or the world and it gets confirmed, maybe that’s not as surprising but I don’t think it detracts necessarily.

You don’t think it undercuts the story itself.

If you’re watching our show—and by the way, we obviously telegraphed it and foreshadowed it as much as we could—and you get the sense that something’s off about this and maybe he is in prison and then it gets confirmed, that doesn’t invalidate anything that happened prior. It should only deepen your understanding of where Elliot’s headspace is. That’s the added layer. It’s almost how like in a scene between two characters, there’s always subtext: they’re not talking about the actual thing that they’re talking about. With our show, it’s a little bit of the same thing: you’re not seeing the thing that is actually going on.

So the fact that people are kind of making a big deal about us surprising them is a little... for me, that’s not the point. I think that’s missing the point to a large extent. I think it’s very impactful when a reveal does surprise you. It can get really exciting, but at the same time, a reveal always has to feel inevitable, because if it’s shock with no basis in reality and no basis in what we’re invested in, then it can just feel arbitrary and like a trick. With us, we never wanted to do that. We wanted it to feel inevitable and to deepen how we’re seeing the story through Elliot’s eyes.

This season’s episode “m4ster-s1ave” featured an amazing 20 minute-long break from reality that turned the show into a dark, Full House-esque sitcom. And there’s a moment where Mr. Robot tells Elliot he’s constructed this false reality to make him feel safer, that “it’ll feel good if you let it.” How did the idea for that sequence come about?

Yeah, this is again that other layer I was talking about when it came to the prison fantasy that Elliot created for himself. It plays on the idea that we create illusions and lies that we tell ourselves to cope with certain traumas or tragedies in our lives. For Elliot, his happy place that he ended up reverting to was that perfect family in a sitcom that he watched as a kid that I obviously relate to and a lot of the other writers in the room related to when we were having this discussion. And it’s an incredibly false reality, to the point where there’s a laugh track and there’s happy music when the problem gets solved at the end of the day. There’s a comfort there in the lie. And once again, thinking about it in terms of layers, we just thought it would be a very creative, entertaining way of showing how Elliot coped with the beating. We could have shown Elliot go through the beating. But we just thought, again, that this added another dimension to how Elliot would cope with that.