When on Monday, April 30, 1945, Winston Churchill learned from Radio Hamburg that Adolf Hitler had died fighting against the Russians in Berlin, he told his private secretary, Jock Colville, “Well, I think he was perfectly right to die like that.” It was only later that he discovered that the fuhrer had in fact committed suicide in the Reich Chancellery bunker, taking his wife of one day, Eva Braun, with him, and thus denying the world the 20th century's most justified execution at Nuremberg.

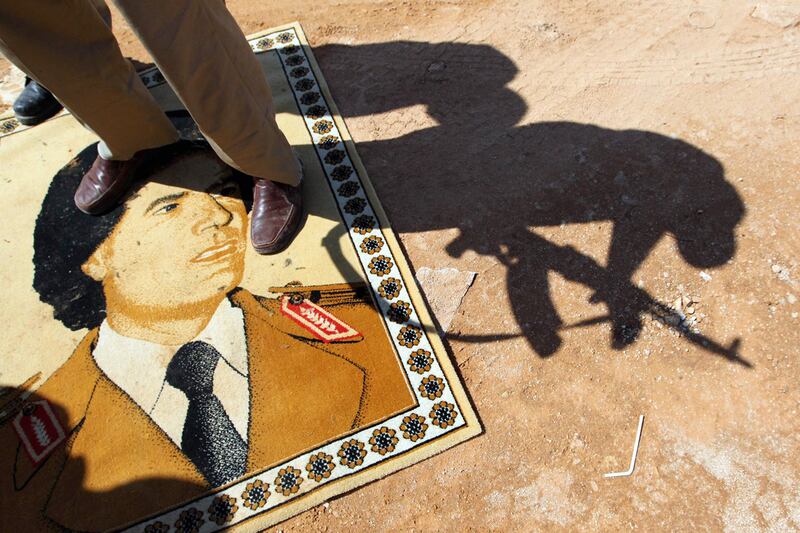

The shade of Churchill would have been similarly impressed with the death of Col. Muammar Gaddafi Thursday, after holding out for over seven months against NATO and the National Transitional Council.

Usually dictators do not actually die on their feet, weapon in hand, as Gaddafi appears to have done. All too often they escape from the countries they brutalized, or are captured and not executed, or (most often) they die in office, full of honors, surrounded by sycophants and only loosening their grip on power when their hands go cold. For Gaddafi to have fought to the last, not escaping to Chad or Niger, but believing in his diseased mind that the silent majority of Libyans still loved him, is quite exceptional for dictators.

When Benito Mussolini’s tiny pro-Nazi Republic of Salo collapsed, he tried to escape across the Swiss border disguised as a private, but was captured by Italian partisans and instantly recognized. On April 28, 1945, he and his mistress Clara Petacci were executed by machine gun in front of a low stone wall by the gates of a villa outside a village on Lake Como. If it seems rather un-Italian to execute a mistress, at least the shooting on Christmas Day 1989 of Romania’s dictator-couple Nicolae and Elena Ceausescu was fully deserved by her, not least because as vice president she had fully shared in his crimes over 37 years. Yet unlike Gaddafi, both Mussolini and the Ceausescus had surrendered, rather than fighting to the death.

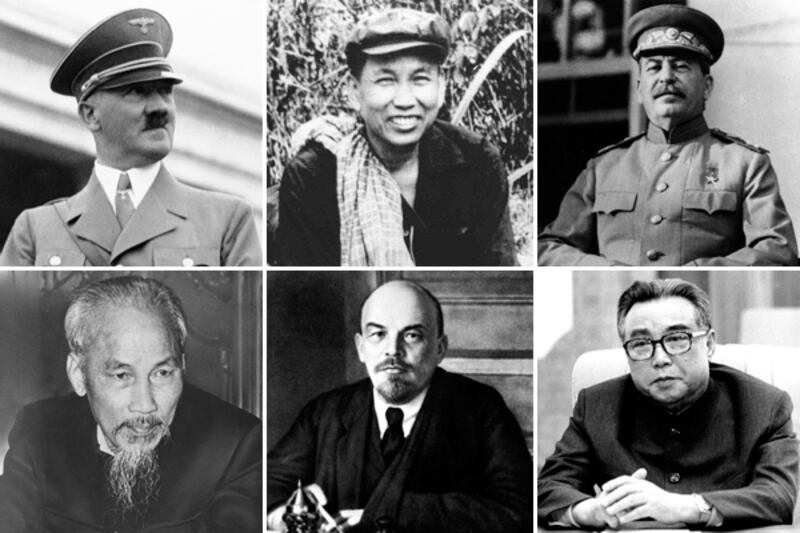

The list of monstrous dictators to die in power is a depressingly long one, and includes Josef Stalin, Gen. Francisco Franco, Mao Zedong, Ho Chi Minh, Marshal Tito, Papa Doc Duvalier, and Vladimir Lenin, the last of whom had survived an assassination attempt. Robert Mugabe, Fidel Castro, and possibly Hugo Chávez all look set to die in power, too, although there must be high hopes that Bashar al-Assad may be overthrown by the brave protesters in Syria, who have already suffered more than 3,500 deaths since the uprising began. Assad is far more likely to flee than to fight to the death, however. Like Gaddafi, Saddam Hussein stayed in his country when the results of his genocidal policies finally caught up with him, but was pulled, hairy and blinking, out of a hole in the ground in Tikrit, although his sons did fight bravely to the death. (At the time of writing it is thought that Gaddafi’s son Mutassim died fighting as well.)

The genocidal Rafael Trujillo of the Dominican Republic paid for his crimes with his life when he was assassinated in 1961. Whereas the case of Antonio Salazar of Portugal was a curious one, in that he slipped in his bath in 1968, giving him a brain hemorrhage, and was replaced in office. But when he regained his lucidity he wasn’t told he was no longer premier, and he died two years later under the impression that he still was.

Many dictators get off scot-free. After his overthrow as dictator of Uganda in 1979, Idi Amin fled first to Libya and then to Saudi Arabia, taking the top two floors of the Novotel Hotel in Jidda, where he lived until his death in August 2003. Similarly, Ferdinand Marcos managed to get himself, his billions of dollars, and his wife Imelda’s shoe collection out of the Philippines in February 1986, winding up in Hawaii until his death three years later. Alfred Stroessner fled from a 1989 coup in Paraguay and lived in Brazil for the next 18 years. Meanwhile, Mobuto Sese Seko escaped Zaire in May 1997 and died in Rabat, Morocco, that September, yet another successful fugitive from justice. Almost alone among dictators, Gen. Augusto Pinochet of Chile actually returned his country to democracy during his lifetime.

Plenty of dictators escape execution even once caught. Pol Pot of Cambodia died under house arrest in 1998, and Slobodan Milosevic of Serbia died of a heart attack in his cell before his verdict was handed down in 2006. Charles Taylor of Liberia is currently on trial in The Hague, where there is no death penalty. Similarly, Emperor Jean-Bedel Bokassa of the Central African Republic was imprisoned for only seven years. He was released in 1993, died three years later among the population he had ravaged, and is suspected even on occasion to have cannibalized. Jan Kambanda of Rwanda has been serving a life sentence in Mali since 2000, considerably more comfortable than the horrific death sentences his henchmen meted out during the 1994 genocides there. Meanwhile, Mullah Omar, the leader of the Taliban since 2002, is still at large.

The moral of the Gaddafi story is that it is very rare for dictators to meet their end bravely, still inside the country they are fighting to recapture. It was fortunate that he chose to stay and fight, rather than destabilizing Libya from abroad, perhaps for decades to come. As he was never going to go quietly, the manner of his demise at long last gives Libyans something for which they can thank Colonel Gaddafi.