The Mueller report answers lots of questions but leaves one big one lingering: Why were so many Russians so eager to ingratiate themselves with Trump World?

The report is in one sense a story of meetings, pitches, and introductions that were entertained but ultimately unfulfilled. “In some instances, the Campaign was receptive to the offers” of Russian help, “while in other instances the Campaign officials shied away," the report says. In any case, no one broke the law with a criminal conspiracy.

Special counsel Robert Mueller reaffirmed the intelligence community’s conclusions that the Russian government directed an online campaign of hacking and trolling to help Donald Trump in 2016. What’s less clear are the intentions of the many Russians who reached out to the Trump campaign offline and whether they were well-connected covert emissaries of the Kremlin or just hucksters trying to latch onto the coattails of a potential president.

Parsing the motivations of the various Russian supplicants is difficult in part because many of them were a mirror image of their counterparts in Trump World: D-listers in their own political hierarchy for whom the line between state policy and personal gain is unclear.

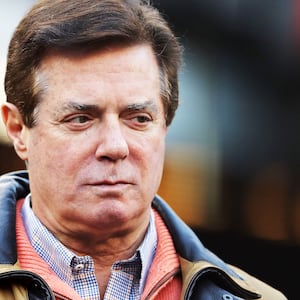

In previous court filings and in the special counsel’s final report, prosecutors wrote that the FBI believes Konstantin Kilimnik, a former partner in Paul Manafort’s consulting business in Ukraine who had worked for the Soviet army as a translator in the 1980s, has “ties to Russian intelligence.” Kilimnik held a Russian diplomatic passport as recently as 1997, and a number of his former associates relayed their belief that the dual Russian-Ukrainian national was, at least at some point, a spy.

Kilimnik, the report reveals, received not just a single briefing from Manafort on Trump campaign polling and messaging strategy in August 2016 but continuous updates via text messages from Manafort’s aide Rick Gates. In turn, Kilimnik passed along a peace plan for Ukraine that Manafort himself recognized as a “backdoor” to recognizing Russia’s de facto annexation of rebel-held parts of the country.

Prosecutors concluded they could “not reliably determine” why Manafort passed along the polling data. Viewed in one light, it certainly can appear as though Kilimnik, a former intelligence officer, was a mere cutout for Manafort to pass Trump campaign information to the Russian government. But prosecutors couldn’t determine what Kilimnik did with the information, and both Manafort and Gates suggested an alternate explanation for the exchange: money.

Manafort had run afoul of Oleg Deripaska, a wealthy Russian oligarch, when an investment fund he tanked lost Deripaska millions and prompted a lawsuit. The report says Manafort had been trying to get back in his good graces ever since he’d taken a job at the Trump campaign. At the Aug. 2, 2016, meeting where Manafort had raised polling and fielded a peace plan, he also discussed the possibility that Deripaska could drop the lawsuit filed after the collapse of the investment fund. Kilimnik, in that sense, was Manafort’s way to kiss up to Deripaska again.

Deripaska’s deep pockets and litigiousness may have drawn Manafort’s focus, but he’s more than just a money man. The Trump administration sanctioned him in 2018 for acting as a representative of the Russian government. His aide, Victor Boyarkin, who the report says ferried messages to Manafort via Kilimnik, is a former GRU officer whom the Treasury Department sanctioned for “providing Russian financial support to a Montenegrin political party ahead of Montenegro’s 2016 elections” shortly before Russia allegedly tried to pull off a coup in the country.

Deripaska’s interest in Manafort may have not been just money either. In January 2017, the report says Manafort traveled to Madrid to meet a Deripaska aide and discuss “recreating [the] old friendship” between the two men but also “global politics.” Manafort sent an email to Trump’s incoming deputy national security adviser, K.T. McFarland, when he got back to the U.S. three days later about “important information” he had picked up “on my travels over the last month.” Manafort claimed it was about Cuba; the special counsel’s office couldn’t say whether that was true. In any case, no one appears to have followed up.

Not all of the Russians pitching the Trump campaign had sinister backgrounds in the spy world.

When the special counsel’s office charged Michael Cohen with lying to Congress, it offered the tantalizing detail that he had met with someone who promised “political synergy” from the Russian government and the ability to set up a meeting with President Vladimir Putin and then candidate Trump. Stripped of his anonymity, synergy man seems a far less impressive operator. Mueller’s final report identifies him as Dmitry Klokov, the director of public relations for a Russian electrical transmission company who had once been a spokesperson for a former Russian energy minister. If he could’ve set up a Putin meeting, he didn’t try very hard—Cohen dumped him after a few phone calls.

Or Natalia Veselnitskaya, the lawyer at the center of the infamous Trump Tower meeting in 2016. The Trump side of that meeting’s intentions were obvious enough from Donald Trump Jr.’s exclamation of “I love it” when Veselnitskaya claimed that she had dirt on the Clintons compliments of the Russian government.

Her hints at government sources have since been borne out by an indictment in New York that alleges that she lied about ghostwriting correspondence for Russian officials to send to their American counterparts. And her clients—wealthy Russians who’ve had money seized on corruption charges—have interests that dovetail directly with one of Moscow’s most pressing foreign policy priorities: the removal of sanctions against Russian nationals and companies. So was she representing her clients at that meeting or the broader interests of the Kremlin? Mueller doesn’t say, but the bait she offered—unsupported allegations about money laundering she couldn’t connect to Hillary Clinton—was far short of tempting.