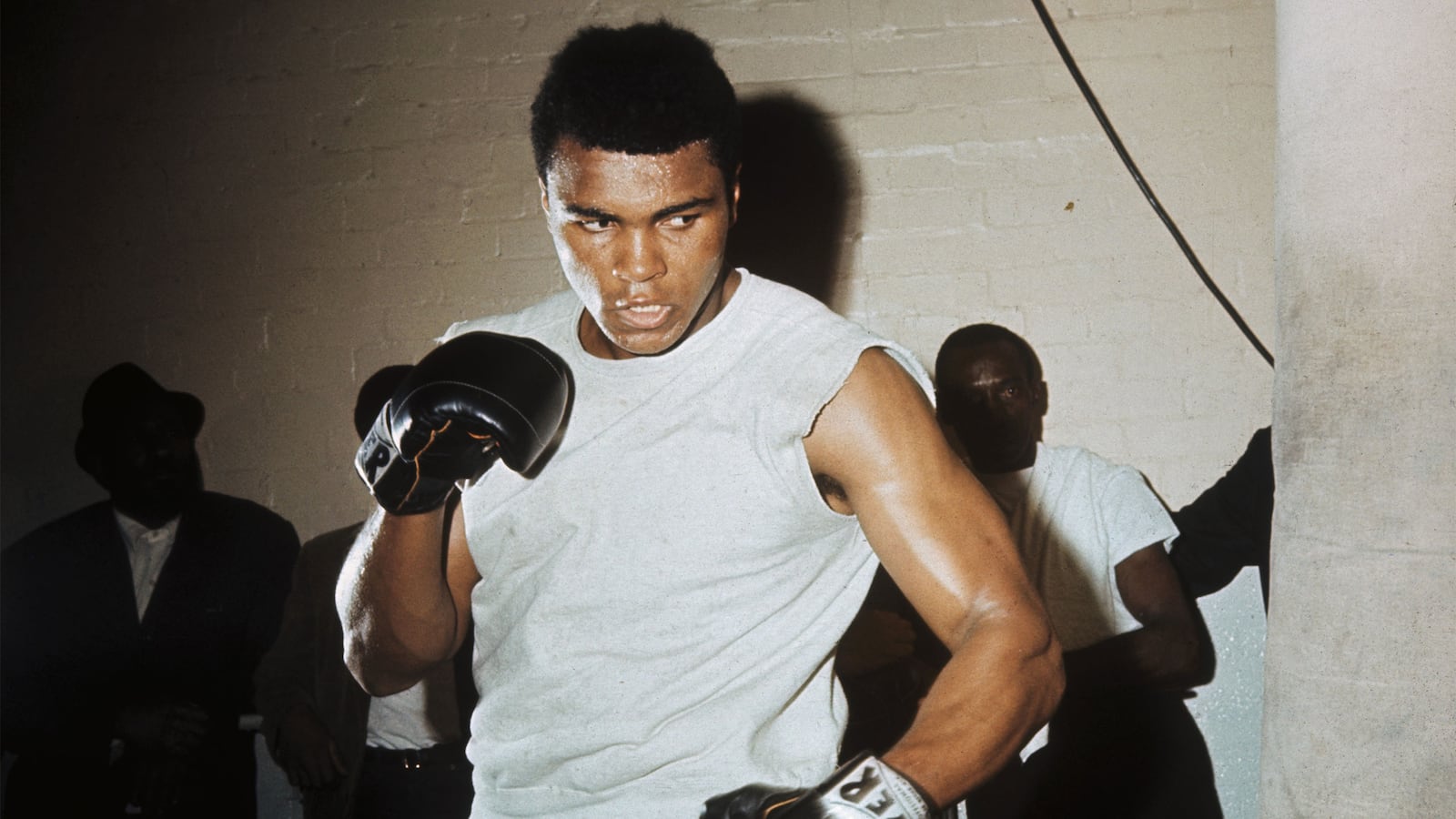

I had thought I knew everything about Muhammad Ali from writing a boxing book of my own and obsessively—and I don’t use that word lightly—following his career. But many of the revelations in Jonathan Eig’s just published, compulsively readable Muhammad Ali: A Life came as news to me.

For example:

- Hours after Ali “shocked the world”—as he aptly put it—by defeating Sonny Liston to become heavyweight champion in 1964, Ali and his new friend Malcolm X celebrated by downing scoops of ice cream at a soda fountain.

- Ali divorced his first wife, Sonji, because of pressure from the Nation of Islam.

- Jesse Jackson believes that Ali never left the Nation of Islam for fear that he would suffer the same fate as Malcolm X, who was assassinated in New York City in 1965.

- Hours before Ali’s “Fight of the Century” with Joe Frazier in 1971, Ali’s second wife Khalila found him in bed with a prostitute. And the day of Ali’s upset loss to Ken Norton in 1973, Ali had been in bed with two prostitutes.

Eig, a former Wall Street Journal reporter who has written biographies of Lou Gehrig, Jackie Robinson, and Al Capone, as well as a history of the birth control pill, conducted over 400 interviews during the four years he spent on his book. The result now stands as the definitive life of Ali: a fair-minded corrective to accounts that paint Ali as something of a saint. At the same time, Eig gives full weight to Ali’s immense pugilistic, political, and social achievements.

“I tried to be really balanced because I do love the guy,” Eig told me during our nearly hour-long conversation. “And I didn’t feel like I was in this to take Ali down. But I want people to understand him and appreciate him for who he really was. We don’t do anyone any favors by creating marble statues.”

So what exactly is the essence of Ali’s achievement other than being the only man to win the heavyweight title three times? Ali himself put it best in what serves as the thesis statement of his life: “I had to prove you could be a new kind of black man. I had to show that to the world.”

Put another way, Ali’s life story could easily be titled, “I Am Not Your Negro.”

Eig, a disarmingly polite and agreeable white guy with a shaved head and welterweight physique, is the physical opposite of Ali. I began our conversation by citing an observation made by the black film maker Melvin Van Peebles—director of Sweet Sweetback’s Badass Song—that America didn’t like Ali until he had been “teddy beared up,” i.e., when Ali was greatly diminished by all the punishment he’d taken in the ring.

“That’s what Stanley Crouch said,” Eig responded. “He said Ali was a grizzly bear and everyone was scared of him. Then he was a circus bear, he was entertaining but still dangerous. Then he became a teddy bear, and he was safe. They loved him. It’s wrong. It’s unfortunate. It’s racist, that’s what it is.”

Ali was born one year after Emmett Till, the black teenager who was lynched in Mississippi in 1955 after a white woman falsely accused him of flirting with her. Ali’s father showed the young Ali a photo of Till’s open coffin to the send the message: “This is what the white man will do.”

“I don’t think we’d be sitting here talking about Ali today if he wasn’t black—and if he didn’t consider race the biggest struggle of his life,” Eig said. “It changed in the second half of his life. He stopped talking about it as much. But the reason he becomes Ali, and the reason that he becomes a thorn in the side of America—and then a hero to America—was as a black person who was doing things he wasn’t supposed to do. He’s challenging white authority.”

Ali absorbed his father’s lessons about race, and when he heard a preacher from Elijah Muhammad’s Nation of Islam advocating a distrust of the white man and black separatism, the message stuck.

Yet Ali’s “itch to rebel,” as Eig puts it, was balanced by his lust for fame and fortune.

“That’s what I love about Ali. He seems like he’s ready to destroy America. There’s no hope for white people. But he also wants to be loved so badly… that he can’t say these things without winking and smiling—putting his arm around Johnny Carson.”

Ali, of course, again stood up to white America in 1967 when he refused to be inducted into the U.S. Army saying, famously, “I ain’t got no quarrel with the Viet Cong.”

The largest misconception about Ali’s opposition to the war, according to Eig, is that Ali “knew what he was doing all along, that he had a core philosophy.” But the facts, Eig said, suggest something quite different: that Ali was improving and adjusting his stance toward the war in much the same way that he improvised in the ring.

“At the first mention of being drafted, Ali says, ‘I don’t want to go over there. I’ll get my head blown off.’ Then he says, ‘Send somebody else, I’ll pay for it. I’ll pay for the bomber jets.’ So he’s not objecting to anything about the war. And then he says, ‘Now wait a second, why should I go when black people in this country are never going to have equal rights? Why should I fight for this country? Go kill some brown-skinned people, that’s not right. Black people are dying over there. Black soldiers are dying in these ridiculous numbers. That’s not fair.’ And then he starts to say, ‘Also it’s against my religion by the way. And I’m a pacifist, a conscientious objector.’”

Ali’s refusal to be inducted into the army, of course, caused him to be stripped of his title as heavyweight champion—and denied the freedom to make his living as a boxer. It was a huge sacrifice that made him something of a martyr to the American left. Ali ultimately triumphed when the Supreme Court, in what Eig describes as largely a political decision, recognized Ali as a conscientious objector based on his religious beliefs, adding a bit of luster to his status as the hero of a very American journey.

“Most men and women don’t know they’re making history until after they’ve made it,” Eig writes, “but Ali worked on the simple and liberating assumption that he was always making history.”

Politics aside, no one would have heard of Ali if he wasn’t extremely good at beating people up.

Eig separates Ali’s boxing career into three phases: the early years during his first championship run when Ali displayed astonishing speed for a heavyweight and a genius for hitting without being hit; the second phase, beginning with his comeback from his three-plus year layoff for evading the draft, when he proved that he could take a punch and survive brutal shots from the likes of Joe Frazier and George Foreman; and the final heart-breaking phase when Ali invited his opponents to pound away on him, taking a perverse—and self-destructive—pride in getting pummeled without falling down. Eig persuasively argues that during this last phase, Ali was awarded several unearned decisions by ring judges who gave Ali more than the benefit of the doubt.

And then there’s the price Ali paid for pursuing his brutal profession.

Eig commissioned Compubox—a firm that counts punches during televised fights—to watch films of all of Ali’s fights. The result: Ali was punched more than 200,000 times during the course of his career. And the number of punches he took increased dramatically as Ali’s career dragged on. Eig also commissioned a study of Ali’s speech patterns to show that Ali’s speech slowed and his neurological decline began as early as 1971, after the first of three brutal bouts with Joe Frazier. Yet Ali continued boxing until his heartrending beating at the hands of champion Larry Holmes in 1980, a fight that, Eig shows, never should have been allowed to take place given Ali’s deteriorating physical condition and his growing experimentation with a drawer full of drugs. Yet the Ali bandwagon kept rolling along because, “there was just so much money to be made.”

So why didn’t Ali quit? Was Ali, something like President Trump, a celebrity surrounded by an entourage afraid to confront him with the truth?

“I do see some parallels in personality with President Trump. He is completely unpredictable,”

Eig said. “He’s flying by the seat of his pants. He thinks whatever he does is right just by the fact that he chose it. And that everything’s going to work out. And a lot of stuff does work out. He gets pretty lucky in a lot of ways.”

Then there’s the Trump-like womanizing—Big Time.

“It’s really interesting to try to play arm chair psychologist and figure out why Ali felt like he could simply sleep with as many women as he wanted,” Eig said. “His second wife said he didn’t really like sex that much, that he was doing it just because he liked people and he wanted to please people. He wanted people to be able to say for the rest of their lives that they had made love to Muhammad Ali. It kind of fits his personality.”

But Ali’s betrayals were not limited to his wives. He turned his back on his friend Malcolm X when Malcolm split from the Nation of Islam. In one devastating scene, Ali cruelly ignores Malcolm X’s wife when she asks Ali to intervene on her husband’s behalf to save his life.

“Ali had to choose between Malcolm and Elijah Muhammad,” Eig said. “And Malcolm was his brother and Elijah was his spiritual father.”

Eig argues that Ali might have prevented Malcolm X’s assassination.

“I think that he had enough clout that he could have gone to Elijah Mohammad and said humbly, ‘I will always be with you, but let Malcolm go do his own thing. You know he’s not a threat to you.’ He could have at least stood up for him and made a plea and made it clear, but instead he said, yeah, he deserves to die.”

Also on the list of Ali’s betrayals is his disgraceful taunting of Joe Frazier, labeling Frazier an Uncle Tom and, prior to their third fight in Manila, comparing Frazier to a gorilla.

“Joe was really a decent guy who went out of his way to try to help Ali, and Ali just repaid him with nothing but cruelty. You can say he was trying to get under Frazier’s skin; he was trying to psyche him out. You can say he was just doing it for PR, trying to get people excited about the fight, but there was a true meanness there. A real viciousness.”

And Ali’s treatment of Frazier was evidence of a double standard, according to Eig.

“I think it appealed to white fans, actually because he was sassing these other black guys,” Eig said. “He’s giving license to whites. And he never treated his white opponents that way. He treated his white opponents way better than he treated his black opponents. Maybe he figured that’s what played to his crowd.”

Yet this man who was capable of great cruelty—as well as great courage—was sentimentalized later in life as a man of peace.

“We turned him into this saint. And it was because we wanted a safe hero who wasn’t threatening to us,” Eig said. “Ali was great. He was a warrior. He loved us. He loved people. And was great with kids and loved the public. And we all wanted to be a part of that. You forget that he was mean. That he was a fighter. That he fought in good ways and bad. For black power, for black pride. He fought against the government. He fought cruelly against people like Frazier.”

It’s a measure of Eig’s achievement that Ali emerges from these 600 exhaustively researched pages as the flawed great man he truly was, an exhilarating figure who seemed to never be overwhelmed by circumstances either in the ring or out.

“I hope this will scrape away some of the barnacles for the people who mythologize him,” Eig said. “But I also hope it will show people why he’s important. Fifty years after his Vietnam protest, you can see why it mattered. Why it was so bold for an African American athlete to say, ‘I don’t have to be what you want me to be. I don’t have to do what you want me to do.’ We’re still arguing that.”