I’m named for my two grandmothers, Mary and Kay, and my mother trained me not to answer to “Mary,” lest I leave her mother out. Growing up, I was lucky to know all four of my grandparents, and my latest novel, American Ending, is inspired by their story: immigrants who face exploitation, discrimination, a pandemic, and the heartbreak of who gets to be an American citizen—100 years ago.

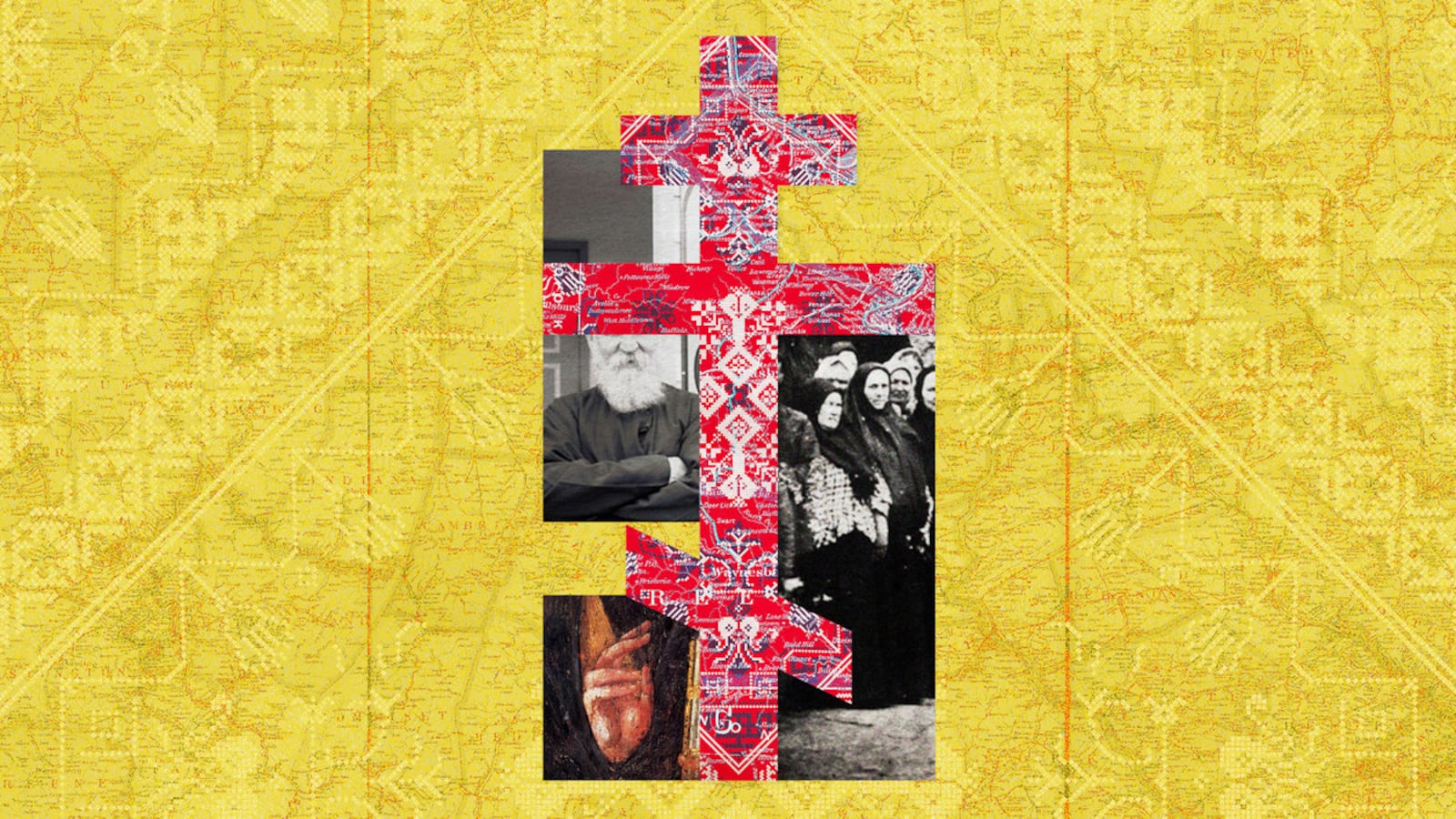

I could not find my people on the bookshelf, Old Believer Russian Orthodox who consider theirs the one true church—Catholics broke off from them. Like most fundamentalist sects, they are rich in rules, starting with food: no milk, meat, or eggs for six weeks before Easter or Christmas, on Wednesdays, Fridays, and saints’ days. During services, which are conducted in Church Slavonic, women and men stand on opposites sides of the church, and the women wear long skirts and cover their hair (which it is a sin to cut; wearing makeup is also a sin). So is smoking, because your body is a temple, but not drinking, because Christ’s first miracle was turning water into wine. They are, after all, Russian.

The two sides of my family arrived here from Suwalki, Russia (now Poland) to mine coal in the Appalachian town of Marianna, Pennsylvania. The men suffered from black lung (as did my maternal grandfather), lost a limb in explosions, or died in cave-ins. The women married at 14 (my paternal grandmother) and gave birth to a house full of children, who in turn became miners or child brides. Their story deserves to be told. Not having it on record furthers the insult that America’s industrial success was fueled by exploiting them, akin to overlooking that both the White House and the U.S. Capitol were built by enslaved people. Both sets of grandparents got themselves out of the mines to Erie, where there was another Old Believer Church—there are only five or six in America.

Toni Morrison famously said, “If there’s a book that you want to read, but it hasn’t been written yet, then you must write it.” Émigré fiction by Russian and Polish Jewish authors abounds; by my people, not so much. Old Believers kept to themselves. They didn’t exactly welcome visitors, members had to marry within the church, and Church Slavonic is not spoken outside of services (my great-grandfather copied the prayer books by hand). Old Believers stopped the clock in 1666, refusing to adopt the Gregorian calendar or any liturgical reforms. Martyrs and priests died defending the one true church rather than change a single word in the Nicene Creed or cross themselves differently, so you can imagine how questioning or spinning tales about them in a novel might go over.

Nonetheless, I was the child curious enough to ask questions. Though my father’s job took us to Oklahoma, my mother read us Russian fairy tales and taught us about the church. Summers, we drove cross country to Erie for large family reunions and church services. My mother’s mother loved the hymns and Russian folksongs. She romanticized their culture, but my Aunt Pearl would have none of it. “Russia,” she’d wave her hand in front of my grandmother, as if to break the spell. “The men drank too much, and they beat their wives.”

They both talked about life in the mines, and imagining what they went through—especially the women—got me started on a book. What made the writing urgent was understanding something my father’s family had been trying to tell me for years. My father and his many siblings, who called his parents Ma and Pa, repeated this refrain: “Ma lost her citizenship when she married Pa.” The aunts and uncles said it like a nursery rhyme, and it had as little sense as one to me. Mary Zuravleff was born in America—in Erie, Pennsylvania—and never moved out of the state. When I searched for her written records, I found her 1908 marriage license, which records her age as 18 (she was 14), as does the 1910 census (she was 16 by then and already a mother). By the 1920 census, her age is recorded as 26, finally her real age, and she has six children, the fifth and sixth being identical twins.

Remember the hoopla preceding the 2020 census surrounding citizenship—Would asking about citizenship keep people from filling it out? Would the answers be used against them? The 1920 census has a citizenship section. The first box asks for the year of immigration, if applicable. That square is blank for my grandmother, as it should be. The next asks the question “Naturalized or Alien?” which should be blank as well. But there is a mark in that square or what looks to be something scribbled out, until you magnify the tiny form. Because on closer examination, I could see that inside the square are the letters “Al.” For alien.

“Ma lost her citizenship when she married Pa.” Alien is a powerful word—a painful word—and that label introduced me to a little-known episode in American immigration law. Starting in 1907, American women who married foreign-born men lost their citizenship! The law didn’t affect American men who married foreign-born women, and when a new law was finally made, the women didn’t get their citizenship restored. If their husbands became naturalized, the Cable Act of 1922 stated, these American-born women who’d been stripped of their birthright could apply to be U.S. citizens. To see my grandmother declared an alien infuriated me, and the fact that no one I talked to had heard of this law made the novel a necessity.

I spun a tale combining both sets of grandparents into one family—telling the story through Yelena, the first American born in her family. These Old Believers leave two daughters behind to come here, which was the case on my mother’s side (they left three behind). In their Appalachian town, boys quit grade school for the mines and girls are married off as teenagers, giving birth to more babies than they can feed. When Yelena and her younger siblings ask Ma for a bedtime story, she asks them, “Russian ending or American ending?” That refrain haunts Yelena’s life, and American Ending became the book’s title.

I wrapped up the first draft during the last presidential administration, as the day’s headlines reported on parents and legislators who wanted to keep America’s unflattering history from our children. I was writing about America’s restrictive immigration laws and a deadly pandemic showing up in World War I veterans, as the America outside my studio was separating immigrant children from their parents and debating whether to include citizenship on the next census. One day, instead of typing 1919, I typed 2019, and I leapt back from my keyboard, as if it had delivered an electrical jolt. In fact, I was shocked to think that everything that was happening in America had already happened.

Right around this time, a local community group invited me to read from my work in progress, and I saw what a different experience sharing this book was going to be. My earlier novels revel in absurdity and invention. At readings, people tend to ask how on earth I made up my characters, or they talk about my humor and playfulness with language. At this event, after I shared my family’s background and read a short selection, people urgently rushed to the podium. They were compelled to tell me stories of their family’s American ending. The book was both beside the point and precisely the point as people told tales of horrific discrimination and unfairness alongside examples of random generosity or luck that turned a relative’s life around. Again and again, people wanted to share their terrible losses as well as their relatives’ heroic efforts to make a life.

Do novelists choose their subject matter or does their subject matter choose them? Writers constantly debate this, and I thought I had been weaving fairy tales and church dogma with the grit and humor of a family I’d mostly had to imagine, incorporating stories here and there that I’d heard throughout my life.

Honestly, it wasn’t until I described my novel to a potential agent that I realized how long this book had been brewing. When my mother named me for my two grandmothers—Mary, who lost her citizenship for marrying my Russian-born grandfather, and Kay, who forced the mining company to pay in cash rather than scrip and then got her husband away from the mines before black lung killed him—could she have imagined that I’d write a novel honoring their stories?