May 2003. In a Tel-Aviv hospital bed hooked up to a beeping heart monitor and an IV dripping morphine into my veins, I heard my wife Franny ask me, “Do you know what you’re going to say to the reporters? The nurse said they’re on their way.”

I knew exactly what I‘d tell the press that day. I was going to quote a passage I had memorized from the Last Sermon of the Prophet Muhammad in 632 A.D. It was my reason and justification for coming to Israel to do a documentary during the Second Intifada. I believed the Prophet’s words could change the world and help solve the Middle East conflict even though I’d just been blown up in a terrorist suicide bombing while making my second documentary, Blues by the Beach.

September 1993. I was in Chicago at the Parliament of the World’s Religions centennial convened at the Palmer House hotel. I was there to get an on-camera interview with Minister Louis Farrakhan for my first documentary, Brother Minister: The Assassination of Malcolm X. The Nation of Islam leader had scheduled a press conference at the event. It was my final opportunity to interview Farrakhan about the assassination of his one-time mentor, Malcolm X.

I went downstairs where many religions had booths: Christians, Buddhists, Muslims, Hindus, Jews, Hare Krishnas, Sikhs, Wiccans, Zoroastrians, all providing literature publicizing their faith. A very tall Arab in traditional Bedouin tribal garb came up to me and said: “Do you know the Last Sermon of Prophet Muhammad, peace be upon him?” He handed me a single sheet of rolled-up parchment tied in purple ribbon. “As-salamu alaykum.”

It was a low-key press conference and Farrakhan was out the door in less than 30 minutes. I never got my interview. I read the Last Sermon of Prophet Muhammad that night. It embodies the essence of Islam and is a declaration of our common humanity. Considering I was doing a film about Malcolm X, who had rejected the doctrine and dogma of the Honorable Elijah Muhammad and the Nation of Islam, one passage in particular stood out for me: “There is no superiority of an Arab over a non-Arab or of a non-Arab over an Arab, or of a White over a Black or of a Black over a White, except by righteousness and piety.”

I was raised Irish Catholic in the Bronx, was a choirboy at St. Patrick’s Cathedral, became a long-haired Jesus freak in California in the early 1970s. And yet, for me, Prophet Muhammad’s farewell message is the true meaning and the perfection of real religion. The Last Sermon “no superiority” quote is on-screen at the beginning of Brother Minister.

That film stoked controversy and a barrage of publicity. In 1994, Malcolm X’s widow, Dr. Betty Shabazz, was shown a clip from Brother Minister, of Louis Farrakhan denouncing her husband, on a Sunday morning show. Reporter Gabe Pressman asked if she believed Farrakhan was involved in her husband’s assassination. “Of course, yes. Nobody kept it a secret. It was a badge of honor,” Dr. Shabazz said. Then, the day after the film premiered in Manhattan in 1995, one of the six daughters of Malcolm X, Qubilah Shabazz, was arrested by the FBI in an alleged plot to kill Farrakhan, whom she blamed for her father’s assassination 30 years before.

After Brother Minister closed, all the attention faded. I had no job and a mountain of debt. I continued to write freelance stories for the New York Post, but I needed a steady paycheck and health insurance. So, I got a union job as a security guard doorman across from Trump Tower on Fifth Avenue where I was employed for seven years. I was working there on Sept. 11, 2001, when the Twin Towers came down.

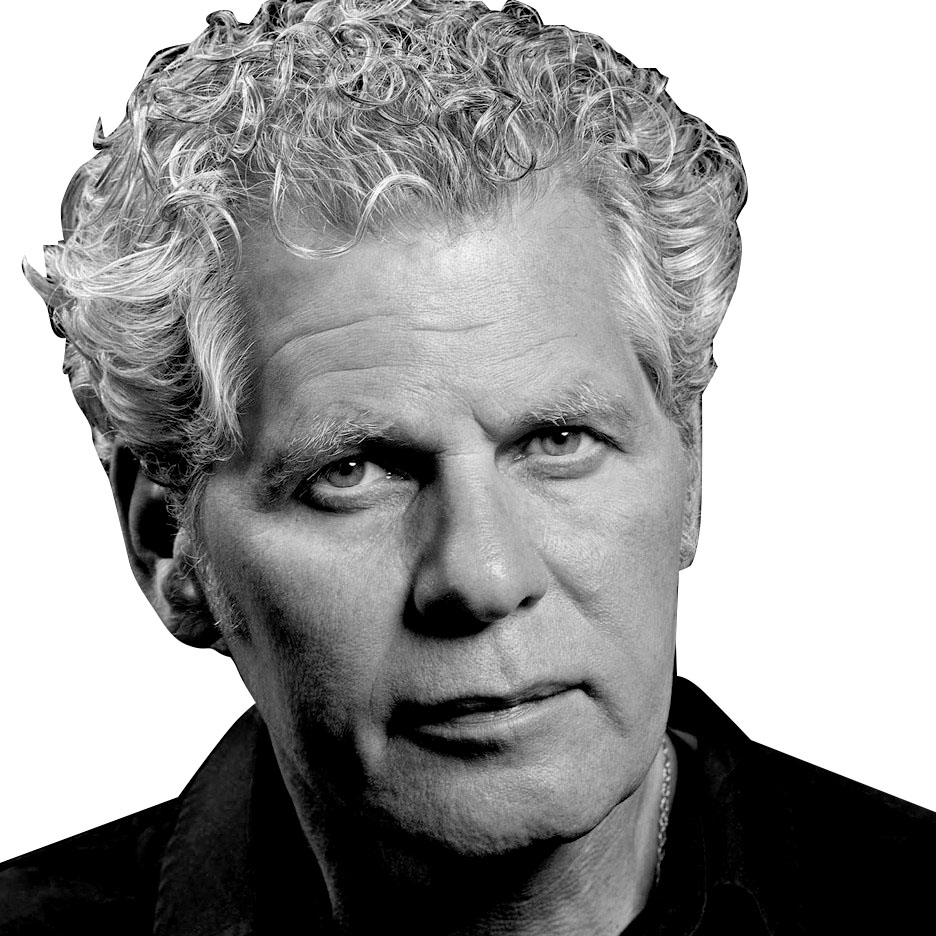

Jack Baxter and wife Franny

Gravitas VenturesIn 2002, Franny and I decided to make a film about peace. We hired a cameraman to film the Muslim Day Parade where I interviewed and got the perspective of Ghazi Khankan, New York executive director of the Council on American-Islamic Relations (CAIR). I heard terrorism experts explain that the reason America was attacked on 9/11 was because of the U.S. government’s support of Israel and Israel’s treatment of the Palestinians. I wanted to go to the Middle East and find a good story that was relevant and true.

“I don’t want you taking buses anywhere in Israel,” Franny told me lovingly. “Grab a cab to the trial. Absolutely no riding on any buses! I’m serious, Jack!”

So, in April 2003, I combined my unused sick days and vacation time and took a month off from my job. I wanted to make a documentary about Marwan Barghouti, a popular Palestinian leader going on trial in Tel Aviv for masterminding terrorism and murder conspiracy charges. Barghouti was once considered the likely successor to Yasser Arafat. Israeli groups like Peace Now said he could be the Palestinian Nelson Mandela, who could broker peace between Arabs and Israelis.

Since it was the start of the Iraq War, I figured most reporters would be covering the invasion and I’d have an inside track on the Marwan Barghouti story. But the first day of his trial, an Israeli filmmaker told me she was already doing a documentary about Barghouti.

It was beyond naiveté—a quixotic quest where I’d imagined myself in the Middle East—somehow using my experience with Brother Minister and Prophet Muhammad’s Last Sermon to help change the world after 9/11. I called Franny and said I was coming home early. Before my flight back to NYC, I took a walk on the beach. I heard live blues music coming from Mike’s Place, a bar next door to the American Embassy.

After telling my tale of woe about Barghouti to the bartender-owner, Gal Ganzman, he said I should forget about religion and politics and do a documentary about “the real Middle East—Mike’s Place.” I looked around and saw Israelis, Arabs and Europeans listening and dancing to the music. I’d found my perfect story!

Three weeks later, I was lying in that bed at Ichilov Hospital when my cameraman, Joshua Faudem, told me that Dominique Hass, a beautiful French barmaid whom we had interviewed for our doc, was dead along with two musicians, Ran Baron and Yanai Weiss. All three were killed mercilessly that night—April 30, 2003—at Mike’s Place. Avi Tabib, the bouncer, survived after fighting one of the terrorists and preventing him from getting inside the bar to kill more people.

The U.S. State Department flew Franny to Israel to be at my bedside when I awoke from my coma three days after the bombing. “The two terrorists weren’t Palestinians,” Franny said. “They were British Muslims who came from England.”

I was readmitted into NYU Hospital with a 104-degree fever when I got back home to New York City. Over the next several years, I saw 18 different doctors. I had surgeries to repair my perforated eardrums and remove “embedded organic shrapnel”—microscopic pieces of the suicide bomber’s body. Even after more than 17 years of rehab and daily exercise, I’m still partially paralyzed on my left side and I walk with a cane.

Jack Baxter

Gravitas VenturesFranny and I were determined to finish the documentary I’d started about Mike’s Place to show there is life after terrorism. We used our savings and Franny’s inheritance from her mother to produce the award-winning Blues by the Beach with Joshua Faudem as the director. For more than five years, we screened the film at festivals and spoke before audiences around the country.

In 2016, producer Avi Bohbot suggested Joshua and I do a documentary on the refugee crisis in Europe that would also be a follow-up to our earlier film. “We should go to England and try to meet with the families of the two British terrorists who attacked Mike’s Place.” Bohbot said he’d pull together the research, logistics and arrange for fixers to assist us in the European countries where we would travel. Joshua’s old Israeli Army buddy, Avi Levi, would be our cinematographer on the one-month shoot in May of 2017.

“OK, I’m in,” I said.

Franny and I would finance it ourselves on one condition: that we call it The Last Sermon.

In February, I was invited to screen the finished film in Tunisia at the 2020 International Human Rights Film Festival in Tunis where it was awarded the Prix de l’Espoir—Prize of Hope. At the 10th Queens World Film Festival, The Last Sermon won Best Documentary Feature. Franny and I were awarded the Truth Seeker Award.

Franny and I believe that the Last Sermon of Prophet Muhammad, peace be upon him, has the power to change the perceptions of Muslims and non-Muslims alike. It's a message of our common humanity, regardless of race and ethnicity, that needs to be known and understood by everyone, everywhere. Our film is a vehicle to communicate that sentiment to a worldwide audience. It’s the film we always dreamed about making.