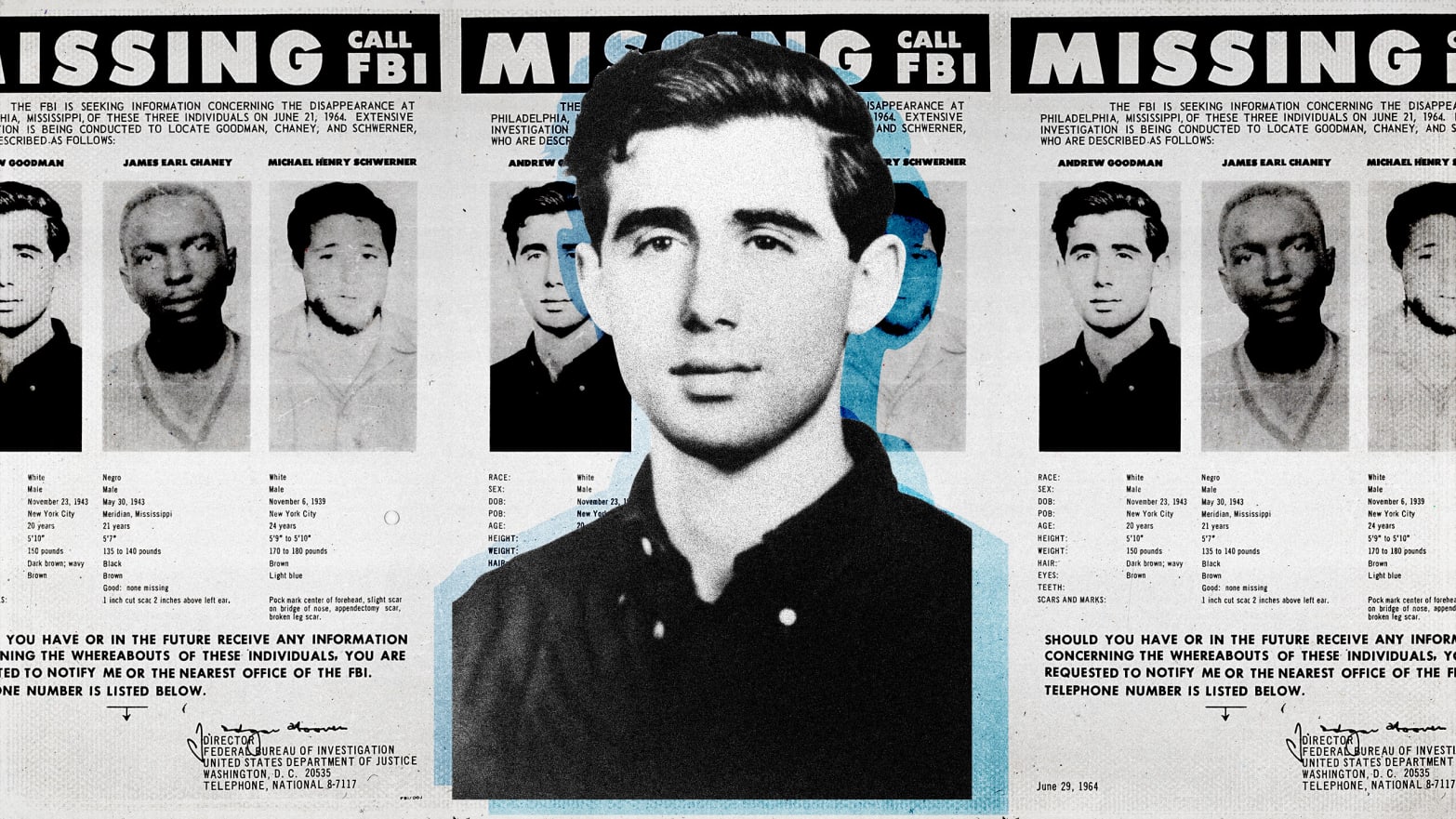

June 21 is the 54th anniversary of the 1964 murders of Andrew Goodman, James Cheney, and Michael Schwerner by a Ku Klux Klan execution squad led by the sheriff in Philadelphia, Mississippi. After the three men disappeared, the FBI and hundreds of Navy sailors hunted for six weeks to locate their corpses, which were discovered buried in an earthen dam.

I met Andy Goodman when we were 6 years old. From first to fourth grade, he and I attended Walden School—an experimental school in New York at 90th Street and Central Park West. At recess, we would play kickball, softball, and touch football in Central Park. One day, Andy tackled me against a granite rock. My lip split and I had stitches. We became friends. One day in nature class, the teacher held out a curling green snake. Andy held it for a while, talked to it, and then carefully gave it to me. I have always been afraid of snakes, but Andy calmed me. He loved Jackie Robinson. I loved Mickey Mantle. I met his mom, Caroline Goodman. We had little sense of politics then.

In the spring of 1962, I went on what was called “a Freedom Ride” to picket a segregated Woolworth’s lunch counter in Chestertown, Maryland. Chestertown was the most segregated place, along with Cambridge, Maryland, on the edge of the North.

Many of us did not know much about the violence visited upon freedom riders in Alabama the year before—one bus burned, white freedom rider Jim Zweig beaten within an inch of his life—except the name Freedom Rides.

On the bus trip down from Boston, a young white woman, a very green organizer, told us that a mob led by the sheriff had attacked the picketers the week before, and a woman had been thrown through the glass window at Woolworth’s. Until that moment, none of us had known just how dangerous our demonstration might be. But we were on the bus, speeding down. We were young. We stuck it out.

When we arrived in Chestertown, we joined a picket line—Woolworth’s new windowpane gleamed in the afternoon sun—and met local people. We heard stories of the previous Saturday (the woman was still hospitalized, recovering). We learned that blacks lived in down at the heels, wood frame houses along two central roads in town and were unable to find employment in stores or restaurants. Jews, we were told, were also despised. We learned of unionizing efforts among mainly black workers at Campbell’s Soup factory. We learned that the mayor had proclaimed, "If you're not born here, you'll always be an outsider."

By late evening, giddy with enthusiasm and relief, we headed back to Boston.

If anyone had asked me in 1964, I would have gone to Freedom Summer in Mississippi. But I had frightening memories of murderous racist rage even in Maryland and feared Mississippi.

By then I had lost touch with Andy, who had become an actor and moved to Queens. But he, like me, had been inspired by the Civil Rights movement and he did volunteer to go down to Mississippi, fearful as everyone was, but hopeful.

Voter registration was the cornerstone of the Summer Project. Although approximately 17,000 black residents of Mississippi went to register to vote that summer, registrars accepted only 1,600 (blacks who could read were dismissed by racist clerks who couldn’t). Highlighting the need for federal legislation, these efforts spurred the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

To address Mississippi’s separate and unequal education system, the Summer Project established 41 Freedom Schools attended by more than 3,000 students. My friend Staughton Lynd, then in SNCC, spoke to volunteers of an intense struggle to reach each person:

“You'll arrive in Ruleville, in the Delta. It will be 100 degrees, and you'll be sweaty and dirty. You won't be able to bathe often or sleep well or eat good food. The first day of school, there may be four teachers and three students. And the local Negro minister will phone to say you can't use his church basement after all, because his life has been threatened. And the curriculum we've drawn up—Negro history and American government—may be something you know only a little about yourself. Well, you'll knock on doors all day in the hot sun to find students. You'll meet on someone's lawn under a tree. You'll tear up the curriculum and teach what you know.”

Andy’s first day in Neshoba County was June 21. Along with two experienced workers—Mickey Schwerner, also from New York, and James Chaney, a black Mississippian—Andy headed for to the Mount Zion Methodist Church, which had been burned out by the Klan for registering people to vote. Their car broke down. The FBI, no heroes in those days, had passed their license number to the state police, which had given it to the local Sheriff, Cecil Price. For the crime of car trouble while advocating equality, they were taken to jail.

FBI/State of Mississippi Attorney General’s Office/Getty

At midnight, the Sheriff “released” them to a huge mob organized by a preacher, Edgar Ray Killen. The mob shot the three men, mutilated Chaney’s body, and buried the corpses in the dam.

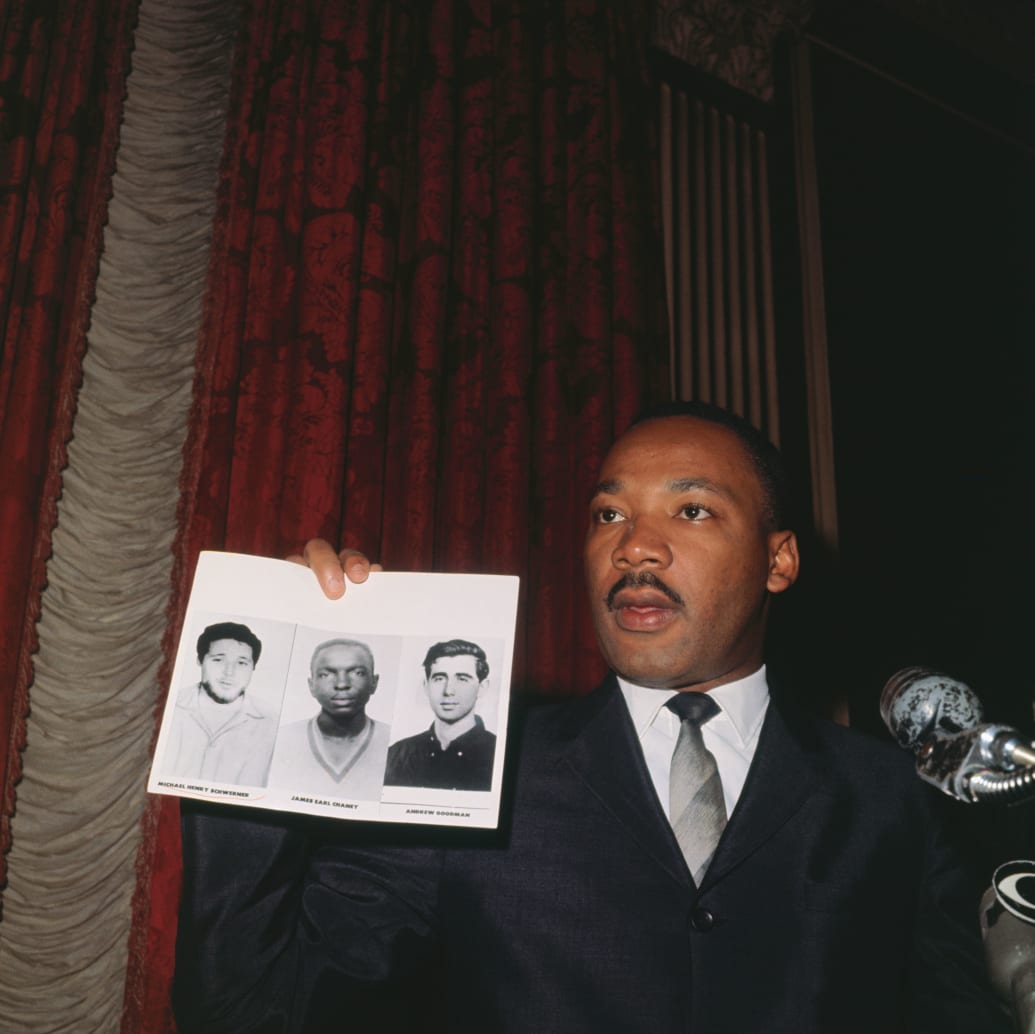

My friend Vincent Harding, who was close to Martin Luther King and wrote the first draft of his speech “Breaking the Silence” about Vietnam, told me what happened the day after the three disappeared. Vincent had known James and Mickey well; he had not yet met Andy. When the three did not make contact by curfew, the organizers knew they were dead.

Community organizer and Freedom Summer architect Bob Moses spoke to all the volunteers. “You should each call home,” he said, “and talk it over with your families. No one will hold it against you if you decide to go home.”

The volunteers spent the day talking in small groups and singing civil rights songs. In the face of sorrow and fear, singing gave them hope.

No one went home.

I read about Andy’s disappearance in The New York Times. Even though I sensed, with foreboding, that the three men had been murdered, I followed the search avidly, and was heartbroken when they were found. It was as if a piece of me were gone. I would have gone to Mississippi with Andy if he had asked me. For a long time, I could not comfort myself. And I felt rage at Sheriff Cecil Prince, at segregation, and at the people in Washington who made such crimes against humanity possible.

Their parents requested that James Chaney and Mickey Schwerner be buried next to each other. But Mississippi had Jim Crow graveyards for black and white, and they were buried separately.

Andy’s body was returned to New York where Bob, his dad, spoke heartbreakingly of equality and how people must go on fighting for it.

At James Chaney’s memorial, David Dennis, a young CORE leader, looking at little Ben Chaney, who had been waiting for his brother to come home and play with him, said, with truth and bitterness:

“I blame the people in Washington, D.C., and on down in the state of Mississippi just as much as I blame those who pulled the trigger... I'm tired of that! Another thing that makes me even tireder though, that is the fact that we as people here in the state and the country are allowing it to continue to happen... If you go back home and sit down and take what these white men in Mississippi are doing to us, if you take it and don't do something about it, then God damn your souls!”

Ben Chaney has had a tough life. So has everyone in the wide community touched by the murders: the trauma extends through the generations.

Bettmann/Getty

But sparks often leap across those generations.

Yolanda Renee King, Martin Luther King’s 9-year-old granddaughter, spoke beautifully in Washington this spring at the march sparked by Parkland students against guns: “I have a dream that enough is enough. That this should be a gun-free world. Period."

In 2005, Sarah Siegel, Allison Nichols, and Brittany Saltiel, three sophomores at Adlai Stevenson High School in Lincolnshire, Ill., took on the “Mississippi Burning” case as a history project with their teacher, Barry Bradford. They spoke with the families and the monster Killen. They worked with others to reopen the case. Caroline Goodman named them “super heroes.” “When I look at your students” she told Bradford, “I am seeing Andy. Their compassion, their drive is the same as his, and it gives me hope for the future."

In 2010, Mickey Dickhof asked me to speak about Andy at the first showing of her film, Neshoba: the Price of Freedom, in Denver. She had interviewed Killen and his words make up much of the film. I missed and conjured Andy, his vibrancy and compassion frozen that day, June 21, 1964, as if in stilled green water, no longer to go forward. Neshoba ends with the thought that no one knows how many bodies, unidentified, are still decaying, nameless, in the Mississippi. And yet, Andy’s hopes are still with me.

Convicted of murder in 2005, Edgar Ray Killen would spend the rest of his life in jail. Befriended by James Heart Stern, a black preacher and cellmate between 2010 and 2011, Killen signed over to Stern his power of attorney and his property in Mississippi. On January 5, 2016—52 years after the murders—Reverend Stern officially disbanded Killen’s Klavern.

I did not go South for Freedom Summer in Mississippi. Sometimes, it startles me that I am here and Andy is not.

But ever since I have shown up often. I dedicated my book Black Patriots and Loyalists: Fighting for Emancipation in the War of Independence to Andy, Jim, and Mickey, who stand in a great movement against so-called white supremacy, long ago and today.

Walden’s main building is named for Andy. His spirit lives on in many friends and companions who are still working for a different kind of society. In Washington and around the country, young people, black and Latin and white and native American and Arab and Jew and Asian and immigrant and citizen join together again and cry out for an end to the rule of guns, war, and militarism, for a new life. Our bloody, racist culture seems ever to exact new sacrifices. Still, as Andy, Jim and Mickey imagined, a new life is possible.