On Nantucket, the ritzy summer getaway for the rich and famous, the average house goes for $4.43 million and hotels are some of the priciest in the country. Wealthy summer residents like former Secretary of State John Kerry and Blackstone CEO Stephen Schwarzman spend summers by their pools or tanning on the beaches, while year-round residents and workers increasingly struggle to pay their rent.

In this island paradise, the solution seems to be causing even more conflict than the problem itself. The proposal of a 13-acre affordable housing development near a popular beach has sparked protests and lawsuits, and turned out record numbers of townspeople at hearings. Angry residents claim the 156-unit condo development will damage the environment and strain resources, and that the developers are using the subsidized housing angle to skirt zoning restrictions. The developers, meanwhile, claim the residents are just peeved about having a low-income housing project in their own—very large—backyards.

Tucker Holland, the town’s municipal housing director, told The Daily Beast it was “the biggest controversy that I can recall in recent years.”

Meghan Perry, another year-round resident and vocal opponent of the project, put it differently.

“I think the developers underestimated our community,” she said. “They didn’t read the room.”

Almost everyone on the island can agree that Nantucket has a major year-round housing shortage. Its popularity as a vacation destination for the luxury class—where a 5,075- square-foot home recently went for $33 million—has led to what the Massachusetts General Court described as a “housing crisis.” According to a study Holland ran last year, when prices were lower, a family would have to earn $530,000 a year to afford the median price of a home. “You have people who are earning what otherwise would be considered very good money… but still struggle to find housing here,” he explained.

The housing crunch is also putting a strain on the island’s workers, from waiters and shopkeepers to police officers and firefighters. Fire Chief Stephen Murphy told state lawmakers in February that the police department had six job openings and another three officers preparing to depart because they couldn’t afford to live there. Brooke Moore, an employee of the island’s affordable housing trust, testified that the food pantry had received requests from three families sharing a three-bedroom house. At the time of the hearing, there were no homes for sale on the island under $1 million.

Legislators have proposed multiple solutions, from instituting a tax on all real-estate transactions over $2 million to raising the town budget by $6.5 million to fund public housing. The cause has even attracted big names—and big wallets—including Wendy Schmidt, wife of former Google CEO Eric Schmidt, who started an economic revitalization project on the island. But progress is slow, and subsidized housing stock comprises less than 10 percent of the island’s total real estate.

In 2018, developers from Nantucket and Cambridge, Massachusetts, weighed in with their own solution: a 156-unit affordable housing development a few miles from the main downtown area, near popular Surfside Beach. The pair, Jamie Feeley and Josh Posner, had previously constructed an award-winning, 40-home affordable housing project on the island called Beach Plum Village. But the new proposal—Surfside Crossing—would be significantly bigger, with 60 stand-alone homes and 96 condos across 13 acres.

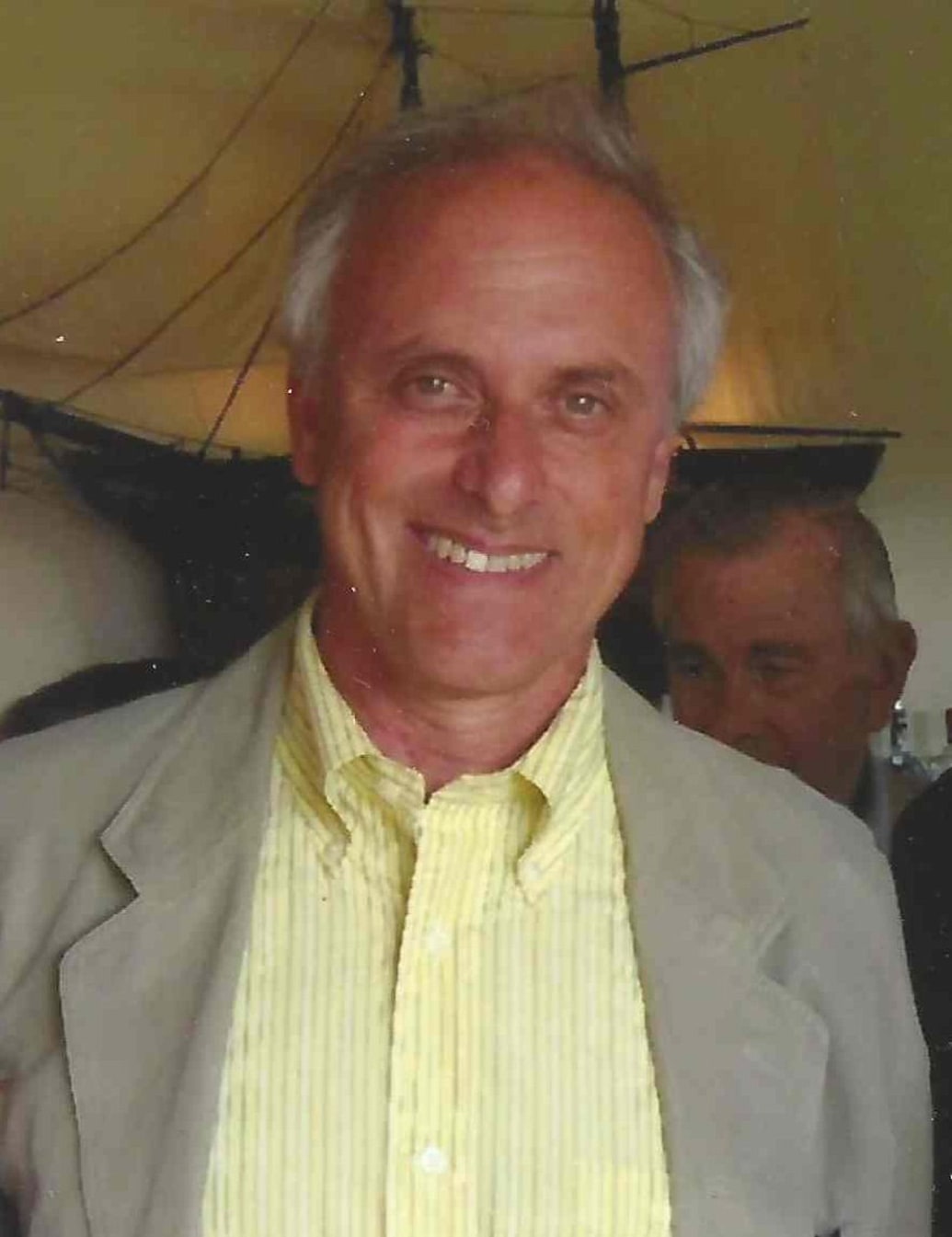

Jamie Feeley

Courtesy of Jamie Feeley

They promised that 15 of the homes and 24 of the condos would be sold for between $261,000 and $373,000, and all of the properties would be under $1 million. They also proposed to use a decades-old Massachusetts law called Chapter 40B, which allows developers to build under “flexible rules” if 20 percent to 25 percent of the units meet the definition of affordable housing. The law also allowed Feeley and Posner to appeal to the state if the Nantucket Zoning Board rejected their plans.

Fresh off their construction at Plum Beach, Feeley—who lives on the island year-round—and Posner, who has spent summers there since he was a child, knew they would face some resistance. When Feeley told the civil engineer at Plum Beach that he was thinking of starting another 40B project on the island, he says he was told to prepare for an “auditorium of 200 people with pitchforks.” (“That really stuck with me,” Feeley admitted.)

Posner, meanwhile, is a 30-year veteran of the affordable housing space, and knew that such projects were rarely popular with the neighbors—even in liberal communities like Nantucket.

Joshua Posner

Courtesy of Joshua Posner

“Most people on the island think affordable housing is the No. 1 problem facing it,” he said. “And yet these attempts to try and do something about it usually have one tragic flaw: They are next door to somebody.”

That somebody, it turns out, was Perry—one of nine residents whose property abuts the proposed development and who ultimately sued to block it. When islanders first caught wind of the plans, Perry and a group of concerned residents formed a group called Tipping Point Nantucket to oppose construction and “educate for responsible development to protect the long-term sustainability of Nantucket’s finite resources,” according to its website. The group’s board is largely composed of year-round residents, but Perry said its membership extends from waitresses and teachers to “the billionaire who just flew in on his plane.”

Perry, who responded with a 1,700-word email when asked to explain her concerns with the development, denies that this is a case of NIMBY-ism, pointing to more than five affordable housing developments that were recently erected. Instead, she says, the issue is protecting Nantucket’s infrastructure and natural resources.

Courtesy of Joshua Posner and Jamie Feeley

Perry pointed to statements from the fire chief, who testified that the development posed a “serious public safety concern,” and to concerns about the impact on the nearby school, traffic patterns, and rare species in the area. She also noted that only 25 percent of the housing development will meet state affordability guidelines.

The developers say the project is about affordable housing, she said, “but in reality it’s not—it’s to spin a profit for the developers that isn't going to benefit us.”

She added: “It’s going to weaken our infrastructure, it’s going to put our first responders at risk, it’s going to put the community at risk.”

Oher islanders agreed. Less than a month after the proposal surfaced, the island’s Select Board penned a letter to the state public housing agency calling the project “entirely inappropriate.” (The board was forced to rewrite the letter several times after residents derided the language as too weak, according to the local Inquirer and Mirror.). In July 2018, the Zoning Board of Appeals was forced to halt a public hearing on the proposal after 150 residents swarmed the meeting room. In August, more than 700 crowded into the high school auditorium for the rescheduled hearing. “If there were a dozen people there in support of the project out of the 700 or 800, I would be surprised,” Holland said.

A community hearing on the Surfside Crossing development, where an attorney asked for a show of hands of who was opposed to the project.

Courtesy of Susan Carey

In response, the developers offered to downsize their project, reducing it to 40 houses and 60 condos, with more open space between buildings and larger, landscaped buffer zones along the property line. When that didn’t fly, they offered to restrict occupancy to year-round residents and employees of local nonprofits, and later, to reduce the number of condos to 40. None of it worked. In April 2019, the zoning board received more than 100 letters in opposition to the project, many of them mirroring the language suggested by Nantucket Tipping Point, according to the Inquirer and Mirror.

That summer, after the local zoning board approved a project just half the size of the original proposal, the developers appealed to the state. When members of the state Housing Appeals Committee arrived to inspect the proposed development area, they were greeted by nearly 100 angry Nantucketers carrying signs reading “Unsafe” and “A threat to Nantucket’s Aquifer.” According to an article in Nantucket Magazine, one of the protesters heckled Feeley, pointing at a nearby, smaller development and yelling, “Jamie, this is a nice development. Why don’t you do that, then we can all go home?”

“[This] is not a neighborhood issue, it's a Nantucket issue,” another, Mary Beth Splaine, told the magazine. “We’ve reached a tipping point where our island cannot bear the infrastructure to go with this.”

“I live next door in what I’d hoped would be my forever home, but I don’t know,” she added. “The neighborhood’s changing.”

The Housing Appeals Committee gave Surfside Crossing its final seal of approval in September 2022, but the fight didn’t stop there. Less than a month later, the developers were hit with three lawsuits challenging the decision, including a filing from the nonprofit Nantucket Land Council that claimed the construction would threaten its work on behalf of public lands. The group of nine neighbors, including Perry, claimed the Housing Appeals Committee had “effectively depriv[ed] them of all opportunities to challenge the massive project to be constructed next to their homes,” while the Nantucket Zoning Board claims the appeals committee “erroneously overturned the Board’s approval.”

“Nantucket should decide for itself how to balance its own resources and priorities,” the land council’s complaint read, “not a state agency in Boston.”

Courtesy of Joshua Posner and Jamie Feeley

While both sides appear to have dug in for a prolonged fight, Holland said he thinks there is middle ground to be found. The developers have floated the idea of setting aside another 25 percent of the development for year-round residents, which Holland said could “bring down the temperature” on the debate significantly. Even Perry said she thought there was an “agreeable outcome” to be had, though she added of the developers: “I don’t think they’ve seen it yet.”

Feely and Posner seem confident that their vision will emerge victorious. Posner said they faced similar legal troubles when getting Beach Plum off the ground, but wound up being permitted to build. They are already doing pre-permitting work for Surfside Crossing, with an eye toward starting construction in the spring or early summer.

“We do hope that as the reality of this and the overwhelmingly positive impact this is going to have on the island sinks in, we won't have to go through the whole legal process,” Posner said. “But if we have to go the whole route, we’ll go the whole route.”