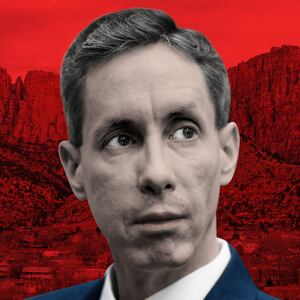

Mormonism has taken a severe beating as of late—at least on the small screen, courtesy of Jared Hess’ 2021 Murder Among the Mormons and Andrew Garfield and Dustin Lance Black’s recent Under the Banner of Heaven, and it suffers another brutal blow with Keep Sweet: Pray and Obey, director Rachel Dretzin’s outrage-inducing four-part Netflix docuseries (June 8) about Warren Jeffs, the prophet of the Fundamentalist Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints (FLDS). Like so many cultists before him, Jeffs fancied himself the mouthpiece for God, and he used his supposedly divine status to create and control an insular polygamous community predicated on the subjugation, enslavement, and abuse of women. That wasn’t enough for Jeffs, however, whose most heinous crime had to do with children—specifically, the countless underage girls whom he married off to adults, or tied the knot with himself, so they could be repeatedly raped and impregnated.

Jeffs is a monster who’s presently serving life in prison for the sexual assault of two young girls, ages 12 and 15, who at the time of his crimes were both his wives. Keep Sweet: Pray and Obey thus boasts at least some semblance of justice. Still, there’s little about this tale that will leave one feeling upbeat. Dretzin’s four-part affair is a history lesson about the modern FLDS movement, which was spearheaded by Jeffs’ father, Rulon, the original prophet, who even in his eighties was continuing to marry as many young women as he could get his wrinkled hands on, including Rebecca Wall, who speaks in detail about the nightmare of having to share a house—and bed—with this elderly creep. Rulon’s word was law in their Salt Lake City community, and while there was shock and confusion when he passed away in 2002—since he’d proclaimed himself the eternal vessel of the Almighty, and yet wasn’t rising from the grave a rejuvenated young man—his followers went along with his devoted son’s elevation to prophet status, as well as his subsequent order that the FLDS flock relocate to the more remote environs of Short Creek, Utah.

Keep Sweet: Pray and Obey is a blow-by-blow account of the past 25 years of FLDS insanity, but its actual subject is religious brainwashing, and the way in which it can take all-consuming hold of receptive (or naïve young) minds. For proof of that, one need look no further than the fact that FLDS members accepted not only Jeffs as their new leader, but his decision to marry some of his father’s sister-wives—who were, in effect, his stepmothers. Such grossness was part and parcel of the FLDS, which indoctrinated members to believe that the end times were coming, and that adhering to the prophet’s commands was the sole route to the celestial kingdom hereafter. Another prerequisite was to have a stable of wives, because that led to babies, and God demanded an army of pious devotees. Consequently, the rules were clear: men required docile and subservient women who would have constant sex with them.

From there, it was only a short leap into systemic pedophilia. As Keep Sweet: Pray and Obey elucidates, Jeffs knew that this particular practice would be frowned upon by law enforcement, and that no amount of demonizing the outside world to his acolytes would change that. In response, he began doubling down on his control over his FLDS clan, replete with building a new compound in Eldorado, Texas, known as the Yearning for Zion Ranch that was supposed to function as the here-on-Earth version of the afterlife kingdom (i.e. Zion) that he kept promising them. In effect, it was just a more self-sufficient fiefdom for him to run—one where he owned all the property, hired and employed everyone (including cops and firemen), and outfitted it with surveillance cameras. He was this enclave’s God, fit to do as he pleased.

Keep Sweet: Pray and Obey is a snapshot of the fear, intimidation, broken families, and sinister misconduct begat by this situation. Mercifully, director Dretzin crafts her portrait with virtually no dramatic recreations, instead relying on a haunting collection of archival photos, home videos, courtroom footage, and recorded evidence to convey the unnerving strangeness of FLDS life, in which women dressed (as one speaker pointedly puts it) like Laura Ingalls, and men preached in holier-than-thou tones that belied their baser designs. That material culminates with clandestine photographs and audio tapes made by Jeffs of his sexual encounters with his victims, which are so predictably disgusting that it’s no surprise they landed him behind bars, where he continues to create “revelations” that are disseminated to his followers.

As is so often the case with true-crime efforts like this, Keep Sweet: Pray and Obey hinges on its interviews with survivors, and in the figures of Rebecca, Ruby Jessop, Alicia Rohbock, and Elissa Wall—whose testimony earned Jeffs an initial conviction for being an accomplice to rape—it captures an intimate sense of the grip that FLDS theology has on adherents, and the means by which the church used faith as the foundation for creating and maintaining a misogynistic paradigm designed to keep women docile and in their place—a state of being that Rulon referred to as “keep sweet.” Their process of learning to see the light and escape their miserable existences turned out to be an arduous one, rendering them ostracized, vilified and cut off from friends and loved ones, and in that respect, Dretzin’s series functions as a celebration of the strength and self-confidence necessary to achieve genuine liberation.

Most of all, though, Keep Sweet: Pray and Obey comes across as a story intent on providing FLDS disciples—and cultists in general—with verifiable proof regarding both the ugly ulterior motives of their leaders, and the possibility of leaving such nastiness behind. Of course, considering that fundamentalist Mormons aren’t allowed access to Netflix (or TV, or the internet), the likelihood of this series changing hearts and minds is probably scant. Nonetheless, at its best, it plays like an exposé designed less for viewers who would never find themselves in these circumstances than for those whose eyes have yet to be fully opened.