Ava DuVernay on the Central Park Five Case and Why She Treated Trump as a ‘Footnote’

Roy Rochlin/Getty

The acclaimed filmmaker and activist opens up about her new Netflix miniseries ‘When They See Us,’ exploring the lives of the so-called Central Park Five, and the Trump of it all.

“It’s just disgusting,” sighs Ava DuVernay.

The Oscar-nominated filmmaker and TV showrunner is discussing the role of President Donald Trump in the Central Park Five case, wherein five teenage boys of color—Korey Wise, Antron McCray, Yusef Salaam, Kevin Richardson, and Raymond Santana—were falsely convicted of the 1989 rape and vicious assault of Trisha Meili, a white investment banker, and subsequently spent up to 14 years in prison.

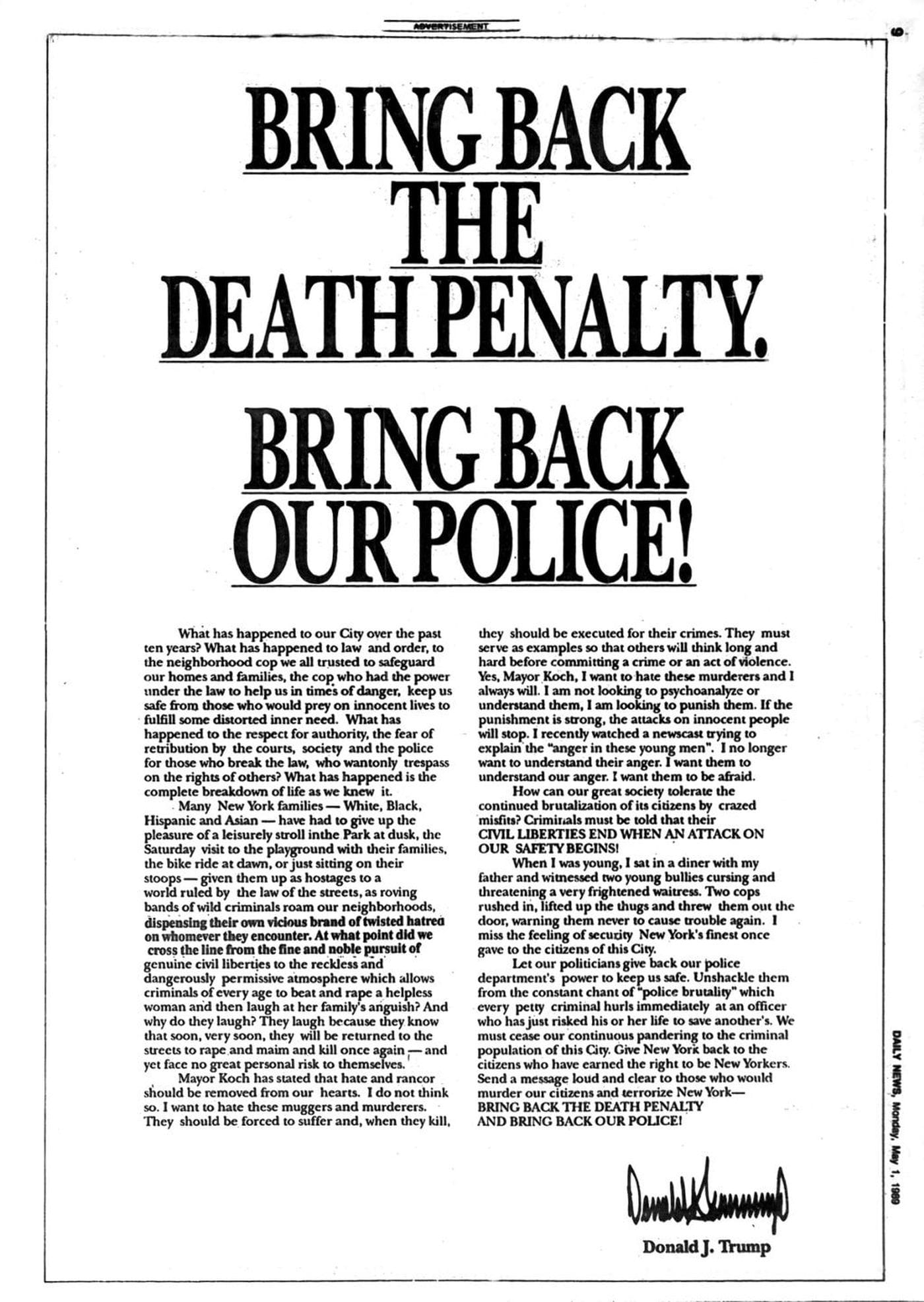

At the time Trump, then a PR-hungry NYC real estate baron who occasionally served as his own publicist, sensed an opportunity for some headlines and inserted himself into the case, inflaming racial tensions with frequent comments to news programs along with newspaper ads, purchased for $85,000, calling the boys “crazed misfits” and urging the state of New York to “bring back to the death penalty,” essentially calling for their pre-trial execution. He concluded: “Maybe hate is what we need if we’re gonna get something done.”

Of course, after having their youth snatched from them through years in prison, the five men—whose confessions were coerced by police after 30 hours of interrogation—were exonerated for the crime in 2002 when Matias Reyes, a serial rapist, confessed to it, and DNA evidence taken from the victim confirmed it was him (to a factor of 1 in 6,000,000,000 people). The charges were completely vacated and the five men were subsequently awarded $41 million from the city in 2014. The settlement prompted Trump to pen a Daily News op-ed railing against the settlement, claiming that he was still convinced of their guilt and that “these young men do not exactly have the pasts of angels.”

When They See Us, DuVernay’s four-part Netflix series on the famous case, provides a riveting—and maddening—portrait of the five boys, chronicling their lives from that fateful night in the park through their respective troubles reacclimating to society. And instead of focusing on Trump, who is relegated to a couple of news clips, it places the spotlight squarely on the boys whose lives were forever changed by an iniquitous system and a media all too ready to feed it.

The Daily Beast spoke with the prolific DuVernay, whose Martin Luther King Jr. biopic Selma helped inspire the #OscarsSoWhite movement, and documentary 13th examined the racist history of America’s criminal justice system, about her latest eye-opening work.

Before we get into your excellent new miniseries, I’m curious when you knew that you wanted to be a change agent?

I definitely never made a decision and said “I want to be a change agent,” I just was always interested in the world of justice. As a teenager, my Aunt Denise introduced me to Amnesty International when I was very young, based on things that I was hearing were happening in other parts of the world. I remember going to my first Amnesty International concert as a young teenager, 14 or 15, and seeing U2 for the first time. And I remember, I had my Amnesty International card and jacket. I felt like there was something more to be a fan of than boy bands, and that’s the earliest thing I can remember in terms of that kind of “formal” activism. But in terms of the community in which I lived, there was always a lot going on in front of me, and I think I was trying to make connections between what I was seeing and ways to remedy them.

And overpolicing must have been one of those things you witnessed in Compton growing up.

Yes, certainly.

I did read that you initially started out in journalism, which is one way of bringing about change. How did your experiences in journalism lead you to fall out of love with it?

I was an intern on the O.J. Simpson unit. As a junior at UCLA, I’d really pursued this internship that was really hard to get at CBS Evening News with Dan Rather and Connie Chung. It was a tough one, because they were one of the only networks that had real active bureaus in Los Angeles. So I got it, and was thrilled. I got it maybe two weeks before the O.J. trial began, was assigned a juror, and my job was to be outside the juror’s home all day. I was never told to dig through the trash or any of that, but it was certainly a competitive environment, because there was an intern on every juror’s house. And I just thought, is this it? Obviously it’s not—there are great journalists out there doing amazing work—but it felt to be the beginning of a tabloid era, even though I couldn’t articulate it at that point. I just knew this wasn’t what I thought it was, or wanted to do, and didn’t think it was completely ethical. So, I found other ways to engage with news and fell into publicity.

Ava DuVernay directs actor Jharrel Jerome, who plays Korey Wise, on the set of 'When They See Us'

Atsushi Nishijima/Netflix

Let’s talk When They See Us. The project was first announced in July 2017, and I’m curious if you were at least in part inspired to tackle it by Trump’s presidential run.

No, no. Trump wasn’t even thought of when we first started this—it was in early 2015 that I first started engaging with this, and engaged the men for their life rights. This started with me and Participant Media, which helped me secure the life rights, so it’s been a four-year process and I don’t even remember thinking about Trump other than his minor involvement in this case at that time. He hadn’t even said his 2016 comments about thinking that they were still guilty, and he hadn’t announced [his presidential run] yet.

This sort of began on Twitter, right?

I followed an account called ‘The Central Park 5’ after seeing the documentary, so this was maybe early 2015 or 2014. And the account had tweeted me, “What’s your next film” after Selma? CP5? So then, I direct-messaged the account and found out it was run by Raymond Santana and asked, “Does no one have your life rights?” It turns out they didn’t, and that began a conversation where I met the men one by one and became passionate about telling their story.

So the project gets rolling in early 2015, and then in June 2015 Trump announces his presidential candidacy. Did it feel like kismet at that point?

No, Trump was never the focus. When Trump announced his presidency, first, I thought it was a joke; and I never would have connected it to this, because he’s not my primary signifier, barometer, or signpost. He’s really a minor part of the story. It’s their story. It’s the story of five boys ripped out of their youth, and the story of their families, which was always my priority. He’s an interesting footnote, but from what you’ll see in the piece, we treat him that way—because that’s what he was in the eyes of the boys as they were going through this chaos and terror. And that wasn’t the chaos and terror of being called names by this guy that owns a bunch of buildings, it was the chaos and terror of having to walk into adult prisons in the moment and experience actual physical danger—and the violations to your life as a free citizen. He didn’t figure prominently in that moment, and to be honest, never really did for us.

What sort of research did you do for this project? And how did you gain the men’s trust?

I got to know them really well. Much more than dinners, I consider them all friends—I’ve been in their homes, they’ve been in mine. Over the course of the four years, I’ve developed personal relationships with each of them that are separate and apart from them as a group. I know their families, have spoken with their families, their wives, various girlfriends over the years, and really had to become immersed in their lives in order to really understand what I could expect and put into a story that best represented them; that, in addition to reading the court transcripts and all the paperwork on the case.

Did you reach out to Trisha Meili for this?

Yes, I reached out to Ms. Meili, I reached out to Ms. Fairstein, I reached out to Ms. Lederer, I reached out to Mr. Sheehan—a lot of the key figures on the other side. I informed them that I was making the film, that they would be included, and invited them to sit with me and talk with me so that they could share their point of view and their side of things so that I could have that information as I wrote the script with my co-writers. Linda Fairstein actually tried to negotiate. I don’t know if I’ve told anyone this, but she tried to negotiate conditions for her to speak with me, including approvals over the script and some other things. So you know what my answer was to that, and we didn’t talk.

And Trisha Meili also declined to talk?

Yes.

There were a lot of big creative choices to make in this film, many of which pay off. Why did you decide to almost immediately thrust viewers into the night of the alleged attack in the park?

I explored a lot of ways of how to get in. You can get in after, like, something happened in the park—let’s go back and find out. You can do it completely backwards, where the men are exonerated and then do it through the case and their redress with the city. You can do it through an investigator who’s looking at the crime, or a lawyer. But for me, it just came down to the boys—to stay with the boys, because it’s their story. When I really committed myself to that point of view it became easy to, even when tempted to follow different people, return to the mission of telling their story. We thought, no, we wouldn’t go have an actor play Trump to go see what he’s doing, because he is not them. We stay with them. And we need to deal with him and others in the way that they were, so he only figures into the story in the way that they feel him, and their parents feel him. I’m just using him as an example, but that’s the way that we addressed every kind of story point that might have taken us down another path.

Although Trump is, like you said, a bit of a “footnote” in this story, he also was one of the people who led the charge in shaping public opinion around these boys.

I have to say, you know, he actually wasn’t the hugest ringleader at the time. Right now he’s the president of the United States, so it figures in when he’s tweeting about the 1994 crime bill and his “staunch advocacy” for African-Americans—all this ridiculousness that we know to be opportunistic, contrived, and manufactured for political gain. But at the time, he wasn’t the only one. Pat Buchanan said that they should be tried, convicted, and hung in a public square; and in 1989, Pat Buchanan was a huge figure. So there were a number of them, and I wouldn’t say Trump was the ringleader. It was New York, he was a businessman, he was looking to get on the map nationally, and it was a sensationalistic thing to do. He was one of many players, he saw an opportunity—he’s an opportunist—and he went for it.

The full-page newspaper ad taken out by Donald Trump calling for the execution of the Central Park Five boys

What were your big takeaways from spending time with Korey Wise, Antron McCray, Yusef Salaam, Kevin Richardson, and Raymond Santana?

They’re broken people. Yes, they can get in on a panel and talk about their experience, but they’re not all completely well-adjusted. There are different levels of that, based on the support that they have in their lives and based on the level of trauma that they’ve experienced, all of which are different. I think the two that are having the most challenging time, even now, are Korey Wise and Antron McCray. Korey Wise lost more than his youth—it was 14 years; he goes in at 16; he was the one in there the longest; he goes straight into Rikers at 16 and never comes out; he’s still in while the others are out; and he endured great abuse and great trauma at the hands of the state of New York.

And Antron McCray’s family was fractured in those precinct interrogation rooms. He basically lost his father in that room, and the family broke apart. That family never recovered. And now that both of his parents have passed away, and his mother passed away just over a month ago—she never got to see the film, and she worked on it with me pretty closely—he’s in a state of brokenness. There’s great trauma there that $41 million from the city, split between the five, with no acknowledgement of what was done, doesn’t really fix.

The film is an indictment of many things and the media is one of them, as the media at the time played a large role in helping convict these boys in the court of public opinion—going as far as printing their names and addresses even though they were underage.

The press coverage was biased. There was a study done by Natalie Byfield, one of the journalists at the time for the New York papers who later wrote a book about covering the case, and it saw that a little more than 89 percent of the press coverage at the time didn’t use the word “alleged,” that we had irresponsibility in the press corps at the time not to ask second questions and literally take police and prosecutor talking points and turn those into articles that people read as fact, and proceeded to shape their opinions about this case that essentially spoils the jury pool, so that these boys were never given a chance.

The real-life Central Park Five, Kevin Richardson, Antron McCray, Raymond Santana Jr., Korey Wise, and Yusef Salaam, attend the premiere of 'When They See Us' at the Apollo Theater on May 20, 2019, in New York City.

Dimitrios Kambouris/Getty

Trump’s comments in his ads that he took out in 1989 were taken out just two weeks after the crime was announced—they hadn’t even gone to trial, so it was impossible for them to have an impartial jury pool. The printing of their names in the papers for minors, and where they lived, was a jaw-dropper. All of this was done by “reputable” papers in New York that we still read, so I’m curious how these papers take responsibility for their part in this, and also possibly use this to review the part they play in other cases that may not be as famous as this.

Your Oscar-nominated documentary 13th also tackled racial inequality and criminal justice reform, and I’m curious what your thoughts are on the Trump administration’s actions concerning criminal justice reform, with legislation like the First Step Act. I recently had a semi-contentious conversation with one of the subjects of 13th, Van Jones, about the Trump administration’s work in this area.

It’s been a disaster. It’s been an upsetting backslide from any of the small gains that were being made prior to him taking power, is what this is. There’s been no instance of legislation protocols, of personnel put in place, any pronounced intention that there is any goal to really create change to build a just system. And so, conversation about it seems to be silly games on a Ferris wheel, because you’ll keep going round-and-round if you take anything that’s been proposed seriously. The context with which it’s being proposed—in an administration that’s done nothing but harm to people of color, to women, to LGBTQ people, to anyone that’s outside of the dominant culture of cis white men—to have serious conversations with serious people wasting breath on debating the merits of any of it is not my focus. Not my focus. So, I leave it to you and Van to have those convos and I wish you well. But to me, it’s pointless.