Billions of years ago, Mars wasn’t the cold, dry hellscape we know it to be. It was warmer—and better yet, it was teeming with lakes and rivers of liquid water, flowing across the planet and carving into the surface to create peaks and valleys for our rovers to explore today. Scientists who study Mars are dead set on trying to determine what locations of the Red Planet may have been home to these former bodies of water—since it’s exactly these places that could have been home to ancient extraterrestrial life.

A new study published Thursday in Science gets us closer to pinpointing where those locations might be. Researchers led by Caltech’s Jay Dickson have found how the global network of gullies located on the slopes of Martian craters seem to have been formed by repeated periods of melting ice. The team built a new model that simulates how conditions on Mars created warmer and frozen geologic periods that fostered liquid meltwater to be produced by melting glaciers and inevitably erode the rocky terrain downslope.

The results ultimately highlight a new set of areas that could potentially be home to fossilized remains of ancient alien life that may have evolved on Mars.

That’s… quite the leap. But where there is water, there’s the potential for life—a significant reason why scientists are interested in learning more about Mars’ ancient watery past.

“We know from a lot of our research and other people's research that early on in Mars history, there was running water on the surface with valley networks and lakes,” Brown University planetary scientist and study co-author Jim Head said in a press release. “But about 3 billion years ago, all of that liquid water was lost, and Mars became what we call a hyper-arid or polar desert.”

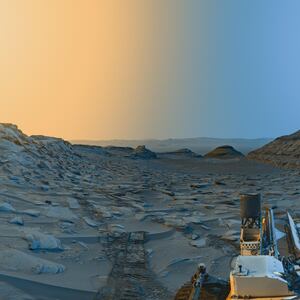

Image of the Terra Sirenum and its gullies captured by the High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE) camera on NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter.

NASA/JPL/Univ. of Arizona.He added, “We show here that even after that and in the recent past, when Mars’ axis tilts to 35 degrees, it heats up sufficiently to melt snow and ice, bringing liquid water back until temperatures drop and it freezes again.”

Some scientists previously thought that Martian gullies may have been carved out by carbon dioxide frost that evaporated from soil and allowed rubble to erode downhill. But the high elevation of the gullies caused others to speculate that meltwater had to have played a role.

The new model developed by the team shows evidence that gullies were formed by periods of melting ice alongside carbon dioxide frost evaporation during other parts of the year. This cycle occurred over and over for several million years, with the last meltwater cycle occurring roughly 630,000 years ago.

That sounds like a long time ago, but in geological terms, it’s fairly recent. And it means the gullies may, in fact, have been a prime habitat for any Martian micro-organisms to have evolved and thrived should other conditions have been met.

“Could there be a bridge, if you will, between the early warm and wet Mars and the Mars that we see today in terms of liquid water?” Head said. “Everybody's always looking for environments that could be conducive to not just the formation of life but the preservation and continuation of it. Any microorganism that might have evolved in early Mars is going to be in places where they can be comfortable in ice and then also comfortable or prosperous in liquid water.”

“In the frigid Antarctic environment, for example, the few organisms that exist often occur in stasis, waiting for water,” he added.

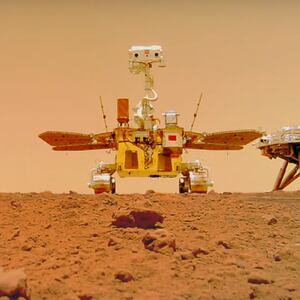

The results come at a very exciting time for Mars exploration. NASA’s Perseverance Rover has the explicit goal to look for signs of past (or present) life on Mars—and that includes collecting rock and soil samples from dried up lakes and rivers that could have been home to life. While it’s not clear whether the latest findings might actually change Perseverance’s mission (or the direction of future missions), they do add additional intrigue that there are more places on Mars worth investigating than we thought.