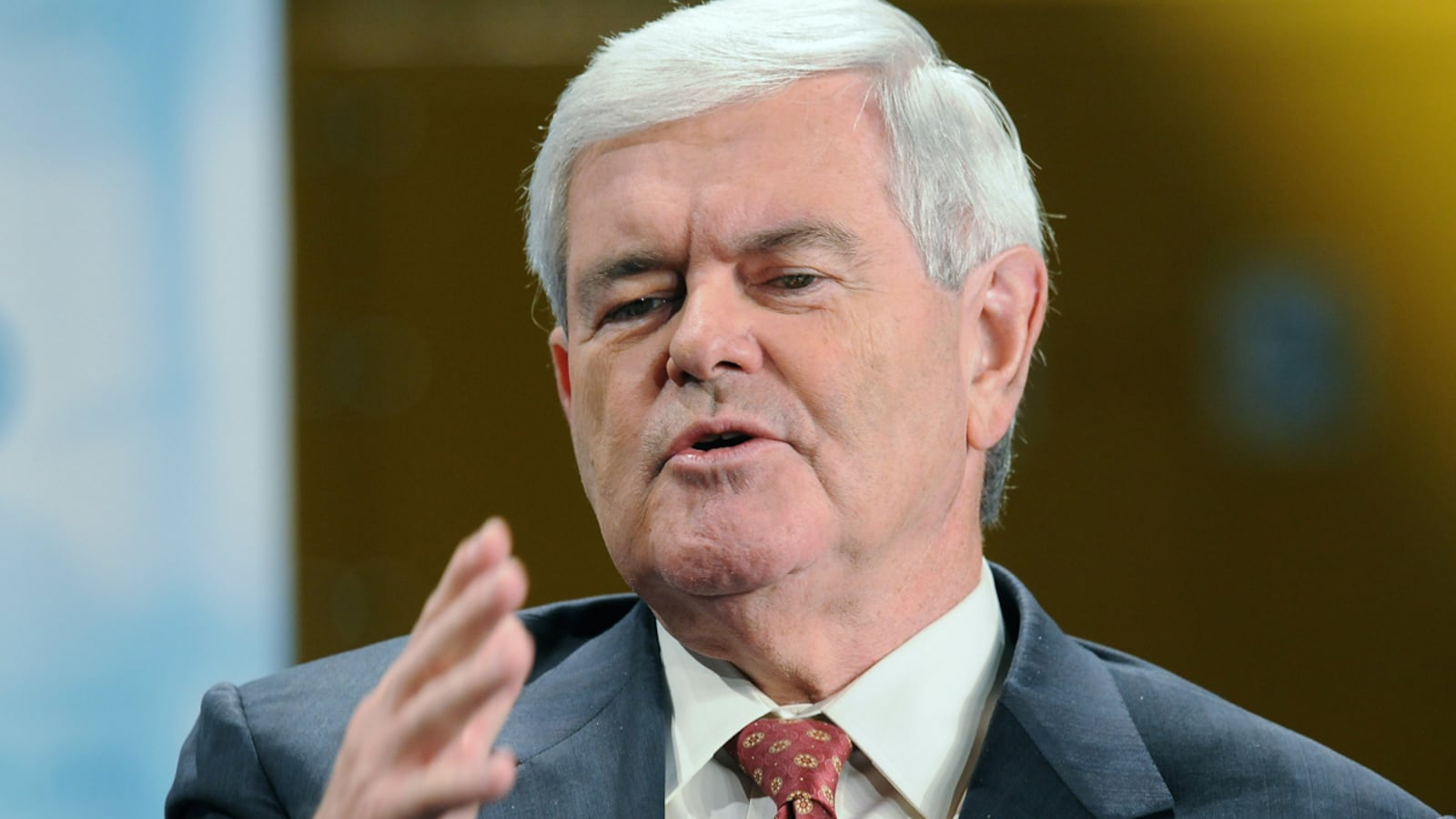

It may have looked as if Newt Gingrich stepped onto the debate stage with every intention of rolling the dice on the volatile issue of immigration.

After all, to take a stand in favor of allowing some illegal immigrants to remain in America, if they are deemed worthy, is to risk offending legions of conservative Republicans who vote in the Iowa caucuses and every contest to follow.

But Gingrich’s campaign insists that wasn’t the case at the CNN face-off on Tuesday night.

“He just answered the question,” Gingrich spokesman R.C. Hammond told me. “He’s given similar answers earlier this year.”

So what explains the explosion of media coverage? “The light is bright, and it’s shining on him,” Hammond says.

That it is. With the former House speaker climbing into first place in some GOP polls, his words carry far greater weight than when journalists dismissed him as an entertaining sideshow.

Mitt Romney’s camp is delighted with the exchange, believing the issue plants Gingrich firmly on the wrong side of the primary electorate. One adviser says he is surprised only that Gingrich didn’t take the plunge in more organized fashion, that he didn’t have statistics and experts lined up to defend his position.

Here is the “humane” approach that Newt outlined when the moderator, Wolf “Blitz” Blitzer, asked about his vote for a Reagan-era immigration-reform bill that many considered amnesty:

“If you’ve come here recently, you have no ties to this country, you ought to go home. Period. If you’ve been here 25 years and you got three kids and two grandkids, you’ve been paying taxes and obeying the law, you belong to a local church, I don’t think we’re going to separate you from your family, uproot you forcefully, and kick you out.” He went on to say that local boards would decide who is worthy and who is not.

Michele Bachmann wasted no time in branding the policy: “Well, I don’t agree that you would make 11 million workers legal, because that, in effect, is amnesty.”

Of course, Gingrich didn’t say he would legalize all 11 million, only some of them.

Romney teed off next: “Look, amnesty is a magnet. When we have had in the past programs that have said that if people who come here illegally are going to get to stay illegally for the rest of their life, that’s going to only encourage more people to come here illegally.”

The conventional wisdom is that this could sink Gingrich, just as defending tuition breaks for children of illegal immigrants was a heavy albatross for Rick Perry. But what if Gingrich was having a Sister Souljah moment, staking out unpopular turf as a way of demonstrating that he’ll stand up for a principle?

(Bill Clinton, during the 1992 campaign, used an appearance before Jesse Jackson’s Rainbow Coalition to criticize the hip-hop artist Sister Souljah, who had been quoted as saying, “If black people kill black people every day, why not have a week and kill white people?”)

Asked about the furor, Hammond says Gingrich’s view is: “People just respect me more for standing up for what I believe rather than waffling around the issue.”

Hammond denied the proposal is a candidacy killer, saying it has majority support in polls. In a May survey of likely GOP primary voters for the Latino Partnership, 56 percent agreed with this proposition: “Provide resources for border security and create a system in which illegal immigrants already in the country could come forward and register, pay a fine including back taxes owed, and be allowed to remain temporarily in this country and work.” That’s not exactly what Gingrich pitched—he said nothing about fines or temporary status—but it’s close.

The reality of the situation is that mass deportations are not practically or politically feasible, even if it’s inconvenient to admit that. “If Mitt Romney is elected president, he’s not going to frog-march 10 million people to the Mexican border,” says Hammond.

It could well be that enough conservative Republicans conclude Gingrich is a squish on immigration that his brief status as the not-Romney alternative suddenly evaporates. Perry had multiple problems beyond immigration when he began to nosedive in the polls. But so far, at least, the negative firestorm predicted by the press has not immediately materialized. If Fox News is any barometer, Gingrich has not been hammered on the channel where months ago he was a commentator. His stance has been analyzed, but there has been no parade of experts denouncing him. And Karl Rove, one of Fox’s most prominent analysts, favored a moderate approach to immigration when he was in the Bush White House.

Gingrich also scored points with the media elite that he loves to castigate. While journalists felt a duty to delineate the danger he faces, some also credited him with taking a sane position that rises above pandering. That counts for bupkis with conservative voters but could help with independents.

Gingrich loves to spout ideas—too many for his own good, even his allies admit—and other positions might hurt him more than the immigration imbroglio. His plan for a Chilean-style Social Security privatization could scare older voters who want no part of an unpredictable stock market. Then there is his demand to abolish child-labor laws, which he called “truly stupid.”

The press, which wrote Gingrich’s political obituary when his campaign imploded in June, collectively believes he did something stupid by expressing concern for illegal immigrants. The coming weeks will determine whether he can again prove the pundits wrong.