To read Wole Soyinka’s memoirs is to encounter many delights. His humor, by turns playful and biting, ranges over the stories he tells. Then there are the stories themselves. Perhaps because he has an unwavering faith in ideas—democracy, progressive politics—or because he does not merely dream of a better world but is eager to roll up his sleeves and lay its building blocks, his life is unusually filled with dramatic incident.

In 1965, amid political tensions, regional elections were rigged by the ruling party in Western Nigeria. The main radio station was scheduled to announce, and thereby legitimize, the fraudulent results. If the announcement could be stopped, then the opposition might have some time to challenge the fraud. Soyinka, 31 years old, a gun in his pocket, slipped into the radio station, and stopped the announcement. Of his action, which has taken on a near-mythical status, Soyinka quips in You Must Set Forth At Dawn, “The Western region was boiling and frankly, I felt deprived of my rightful share of action.”

He was arrested, tried and, thanks to a technicality, acquitted. Two years later, Nigeria’s fissures had widened. The central government was unpopular, and a group of young Army officers carried out a coup. They were unsuccessful, but because most of them were ethnically Igbo and most of the politicians killed were Northern, the coup itself was perceived in the North as an “Igbo coup.” There, thousands of Igbo people were massacred; in other parts of Nigeria, they were attacked, arrested, harassed. Most fled to the east. Soyinka, already a well-known writer, spoke up against the federal government for doing little to stop the carnage, and against some non-Igbo for their complicit silence.

When the easterners seceded and became the independent state of Biafra, Soyinka was sympathetic to their grievances but did not support secession. A true confederation, he believed, was the answer. Nigeria declared war and Soyinka threw himself into efforts to prevent it. He lobbied to ban the sale of arms to both sides. Then he decided to sneak into Biafra and persuade its leader of his position. The meeting, unsurprisingly, did not go as Soyinka had hoped. Back in Nigeria, he was promptly arrested. He spent two years in prison, often in solitary confinement. Much of The Man Died: Prison Notes of Wole Soyinka was written on scraps of paper and tissue during his humiliating imprisonment, and his language sometimes takes on the terse poetry of a man grasping on to his sanity. He would have been imprisoned again—or worse, perhaps—in the 1990s, if he had not escaped Nigeria. The country was choking under a murderous military dictatorship and Soyinka was an outspoken, unapologetic campaigner for a return to democratic rule.

Some of his political actions can, in retrospect, seem quixotic, but they speak to an admirable courage of conviction. He complains about the cost of his politics on his creativity, the obligations that numb his ability to write for long stretches of time, but only half-heartedly; he does not seem to think that he truly has a choice. There is no pause to interrogate his own immersive activism. Even his instincts seem aligned with his ideology. He is, in the accounting of his own life, an actor more often and more completely in a political space than in any other.

In You Must Set Forth At Dawn, he writes that his constituency “was always wide – in the creative industry, in home politics and those of the continent, in issues of human rights—which for me includes the right to life, a commitment that led to my creation of a national road safety corps and the unglamorous labor of hounding homicidal maniacs off the Nigerian highways and educating them the hard way.” Writing of this sort can easily become arid, but undergirding—and redeeming—Soyinka’s account is a purity of purpose. Between a secular moralist and an ideologue, there is a softer, more human middle that Soyinka occupies.

The first time I met Wole Soyinka, at an American literary event dinner, he offered me a small vial of hot pepper.

“You know their food is tasteless. So I always carry pepper with me,” he said. Surprised and utterly charmed, I said, “Thank you sir.”

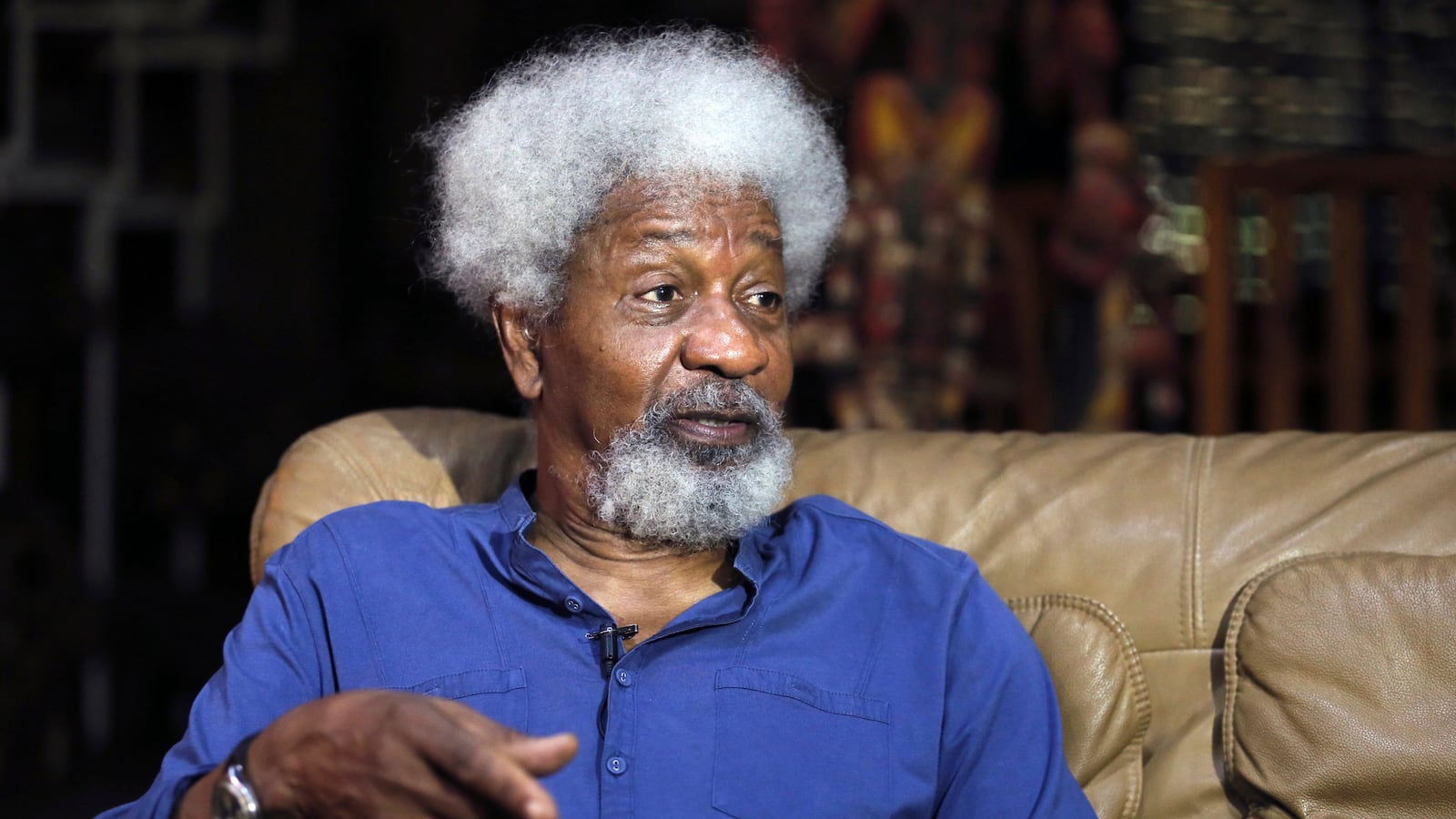

Soyinka has just turned 80. He is a striking man, slender, sprightly, supple-skinned. He has a lean, crackling energy about him, a sense of dramatic flourish, a resonant voice that is not unaware of its own music. In Lagos, street artists display sketches of him. He is recognizable to the average Nigerian, mostly because of his glorious hair, a big effervescent halo, which in his own words is “a landmark of luxuriant moss that passes for a head of hair.”

That description is from his account of his complete loss of anonymity after winning the Nobel Prize in 1986. (“I was set up in a luxurious hotel where if I chanced to sneeze, the management came running. I was provided with an escort who was extremely pleasant and charming but talked my head into a coma.”)

Nigerians stopped him on the streets. They invited him to their events. They assumed he was now a close friend of Bill Gates.

More Nigerians are prouder of Wole Soyinka than have read his large body of work—plays, essays, poems, fiction. He is known to be difficult, because of his love of the Latinate, and his non-linear, digressive, even symphonic, narrative style. In his language, formerly imprisoned people are not “free,” they are “at liberty.” His sentence choices echo not only certain mainstays of his generation of educated Africans—the King James Bible, Shakespeare—but also his personality. He is a man who bristles and chafes at restraint. As does his language, with its maximalist exuberance. But his reputation for being difficult is exaggerated.

Sometimes his style—the mechanical density of his sentences—seem intended to form a protective shield, to keep emotion at a remove, not only for the reader but for Soyinka’s own interiority. Lamenting his incarceration, inThe Man Died, he writes, “I must dig into my being and understand why at this moment you have the power to affect me. Why, even when I have rationally rejected the tragic snare, I am still overcome by depressive fumes in my capsule of individualist totality.”

But, often, he cracks open. About an Igbo woman who was mistakenly brought into his cell after the Biafran secession, part of the stream of those unfairly arrested in Lagos, he writes:

“She came forward, her hand patting the table as if to engage some reassurance of concrete things. I watched her silently. She needed no further comforting from me; the sight of my chains had done more than words could have done for her, calmed her.” The woman recognizes him and bursts into tears, just as guards come into the prison.

“They led the woman away, calmer, stronger. She turned around at the door, looked at me in a way to ensure that I saw it, that I knew she was no longer cowed, that nothing ever again would terrorize her. I acknowledged the gesture. I wondered if she knew what strength I drew from the encounter.”

He gestures to such emotions, grapples with them, but a direct engagement—an open admission such as this—is rare. His is a particularly taciturn manifestation of masculinity. He writes with affection about his male friends—the poet Christopher Okigbo consistently visits him in prison—but of other parts of his personal life, little is said. There is a fleeting mention of his wife, and only because half her wardrobe is given up to his Igbo friends who dressed as women to escape Western Nigeria.

Soyinka is a food and wine enthusiast, but he also sinks easily into a kind of ascetic mode and fasts regularly. He is irreligious in the conventional sense, but his world teems with beliefs. On the day his mother dies, he is at an airport check-in counter when he is overcome with an intense feeling that something is about to happen. He cancels his trip, returns home, shuts all his windows and waits. Soon, someone comes with the news that his mother is gone. The scene is written with a matter-of-fact restraint that lends it great power.

There are other delights in Soyinka’s memoirs: his sharp impatience for platitudes, his generosity, his acute sense of the absurd, perhaps most baldly-drawn in Ibadan: The Penkelemes Years and his (often-disguised) collectivist yearning. In the early 1960s he drives through Nigeria, nurturing a spiritual connection to the road, and learning about his newly-independent country.

“Another trajectory took me through Oyo, city of the fiery god Sango, leathercraft and decorated guords; Oshogbo, watched by her river goddess, Osun, Ilorin, Bida of glass beads and hennaed women, then Minna, scattering hordes of monkeys and apes; plump mouth watering guinea fowl all the way to Kaduna, Kano and Maiduguri of dry dust, turbaned horsemen and minarets … the confluence of the great rivers, Gboko and Abakaliki – pounded yam and roadside venison, Awka of furnaces and roadside Smithies, calabar of fiery ogogoro and light-skinned pulchritude, the sweep of the Niger through Port Harcourt, gathering towards its assignation with the sea”

To read this lovely passage, especially in today’s terrorism-scarred Nigeria, is to imagine what could have been, and what still could be. The romance of Soyinka’s adventure becomes, also, a symbol of Nigerian possibility.

In You Must Set Forth At Dawn, his friend Femi Johnson visits him in detention, a day before the verdict of his trial. His friend stares in astonishment at Soyinka, who seems unperturbed.

“Tomorrow is the day isn’t it?”

“You mean, the verdict?” Soyinka replies.

“What else is there tomorrow?” His friend, exasperated, then adds, “Wole, eda ni e.”

Soyinka translates this as “You are not normal.” “Not normal” might as well also mean “remarkable.”