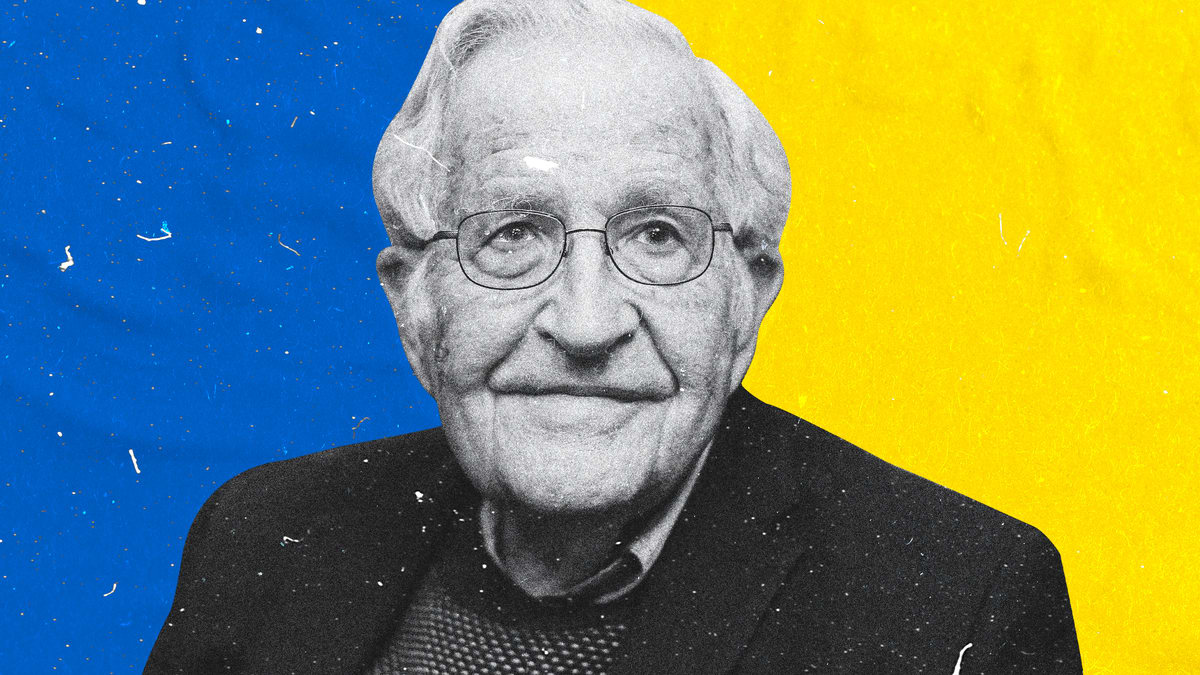

Noam Chomsky, the esteemed linguistics professor, prolific author, and radical activist, was trending on Twitter this past weekend over comments he made about Ukraine and Russia.

In an interview with Nathan Robinson at the left-wing magazine Current Affairs, Chomsky accused the United States of being willing to “fight to the last Ukrainian” rather than pursue a negotiated settlement that, however imperfect, would at least stop the bloodshed in Ukraine. A mutually agreed-upon detente would have the added benefit of slamming the brakes on a dangerous escalation in tensions between the U.S. and Russia.

The dominant tone of the Twitter responses was angry and dismissive. More than a few people made analogies to Chamberlain capitulating to Hitler at Munich. Others called Chomsky a Putin puppet or even claimed that the linguist wanted Russia’s “war of genocide” to succeed more quickly. Even far more level-headed critics suggested that what he said was inconsistent with the general right of people facing foreign aggression to defend themselves—and with Chomsky’s own support, for example, for Palestinians resisting Israeli occupation.

A closer look at the interview, though, shows that nothing Chomsky said merits these criticisms. In fact, in an atmosphere less charged with war fervor it would be easy to imagine The New York Times editorial board saying many of the same things. And there’s no inconsistency in Chomsky’s approach to Russian and western imperialism.

Nowhere in the interview did he suggest that Ukrainians should simply lay down their arms, asking nothing in return. Nor did Chomsky blame Ukraine for Russia’s invasion or deny that the Ukrainian government had any agency in determining its own course of action.

In fact, he repeatedly praised Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky for being “an honorable person” who has shown “great courage” and “great integrity.” Even those of Zelensky’s requests that could have truly catastrophic consequences for the world, like his call for Western powers to establish a No-Fly Zone, are, Chomsky said, understandable from the Ukrainian perspective.

In other interviews Chomsky has also said that Zelensky was right to reject Russia’s immediate demands and that the Ukrainian president’s public response to Putin back in March was “judicious and appropriate.” None of this means that Chomsky and his critics don’t have real and deep disagreements about American policy toward the war in Ukraine. It’s just that the source of that disagreement lies elsewhere.

Chomsky’s analysis is that the options are, on the one hand, a serious push for Russia, Ukraine, the U.S., and other powers to sit down and hammer out a negotiated settlement to end the fighting or, on the other, continued escalation in which, at best, countless additional Ukrainian lives will be lost. At worst, the regional war could escalate into a broader conflict that could lead to World War III.

A common objection to this kind of argument is that worrying about World War III leaves the U.S. and its allies open to “nuclear blackmail” from Putin and other nuclear-armed bad actors. But it’s ahistorical to treat this as a new precedent.

Concerns about proxy wars between a nuclear-armed power and a peripheral country supported by a rival power escalating into direct conflicts between the superpowers have been a staple of great power politics for many decades. It’s one of the reasons that LBJ held back from a full-scale invasion of North Vietnam. And it’s a concern that certainly would have weighed heavily with then-Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev and his advisers if they’d ever seriously contemplated getting more directly involved in the war.

Even if we assume for the sake of argument that there’s only one half of one percent chance that tensions between the United States and Russia over Ukraine could escalate into World War III, that should be more than enough to keep decision-makers up at night. Think about how excited you would be if the odds against your winning a multimillion-dollar lottery jackpot were only 200-1.

And, even if we put aside the slim but terrifying chance of World III, Chomsky still has a point.

The line about “fighting Russia to the last Ukrainian” was borrowed by Chomsky from Chas Freeman, Bill Clinton’s assistant secretary of defense in the early 1990s. The point made by both Chomsky in the interview, and Freeman before him, is that even as the Biden administration has been lavish in its military aid to Ukraine and eager to inflict maximum economic pain on Russia through sanctions, it has shown little interest in direct American involvement in peace talks. That suggests that right now the U.S. is holding out hope for complete Ukrainian victory and isn’t ready to accept a messy process of negotiated de-escalation.

Perhaps pushing hard for outright Russian defeat, no matter how long it takes or how many lives are lost, is the right course of action. A common refrain from Chomsky’s less vitriolic critics is that the U.S. shouldn’t be involved in peace negotiations because, as national security commentator Nicholas Grossman puts it, when and whether the Ukrainians accept a peace deal should be “their call.” Others have suggested that there’s an inconsistency here. Pundit Zaid Jilani asks if Chomsky would advise “the Palestinians or the Kurds” to “give up their national aspirations” simply to avoid bloodshed.

As a matter of fact, Chomsky has endorsed much deeper compromises in the Palestinian case than the Ukrainian one. He’s been a supporter for decades of a two-state solution. He’s also been a critic of the BDS (“Boycott Divestment and Sanctions”) movement.

In his discussion with Robinson, Chomsky suggested that a peace deal in Ukraine might involve a diplomatic commitment to Ukrainian neutrality as well as “some level of accommodation for the Donbas region, with a high level of autonomy, maybe within some federal structure in Ukraine and recognizing that, like it or not, Crimea is not on the table.”

Recovering Crimea and joining NATO were aspirations Ukraine was never likely to fulfill, and it’s hard to see how a negotiated compromise between the parties wouldn’t involve some level of accommodation for the breakaway Russian client states in the Donbas region. The fact is that any such settlement would involve sacrificing Ukrainian “national aspirations” to a much lesser degree than a two-state solution in Israel/Palestine would compromise historic Palestinian aspirations.

Even in the best version of such a solution, where Israel retreated to its pre-1967 borders to allow the formation of a Palestinian state in all of the West Bank, Gaza, and East Jerusalem, the vast majority of the total territory of Israel/Palestine would end up in Israeli hands. And given Israel’s settlement policy over the course of the last several decades, it’s likely that any two-state settlement would leave the Palestinians with even less territory than that.

Moreover, for a good analogy to hold, the U.S. would have to first switch sides and then funnel vast amounts of weaponry to Hamas and Fatah to fight the Israeli army—all the while showing little interest in pursuing a negotiated settlement that, however imperfect, would at least create a Palestinian state.

Would many of Chomsky’s critics really support such a policy?

The complaint that Chomsky and Freeman are denying Ukrainian agency when they accuse the U.S. of being willing to “fight Russia to the last Ukrainian,” or that American involvement in peace talks would deprive the Ukrainians of the right to make such decisions, misses the point on multiple levels.

First, there are reports of Zelensky himself urging “the West” to be “more involved in negotiations to end the war.” U.K. Defense Secretary Ben Wallace has let it slip that he “knows” that the Ukrainians want the U.K. and other powers at the table. And it’s a matter of public record that Zelensky has said that “the world” and not just Ukraine “needs to talk to Putin.” So there’s at least some evidence that the U.S. and other western powers taking a less standoff-ish approach to negotiations would itself respect Ukrainian wishes.

Second, even if Zelensky didn’t want the U.S. at the table, the U.S. has a long history of both working to entice both sides of conflicts to engage in peace talks and taking a direct role in the negotiations. Was it illegitimate, for example, for the U.S. to pressure both the U.K. and the Irish Republican Army (IRA) to make peace in the 1990s? Here it’s not Chomsky, but his critics, who want to apply strange new standards to global diplomacy.

It’s one thing to argue that the U.S. should scale back its role in the world to the point where it would no longer make sense for it to be involved in negotiations about conflicts in distant parts of the world. A great many Americans would reject this suggestion out of hand as “isolationism.” I’m not one of them.

But whatever you think about that question, we can’t have it both ways—if the U.S. can get involved by flooding the conflict zone with weapons to help the side we favor win, then it’s surely not too much meddling for us to promote peace negotiations.

A final point about this: American-led international sanctions have inflicted deep pain on the Russian economy. Surely, American diplomats directly participating in the talks and offering to lift those sanctions would be a major enticement for Russia to agree to the sort of peace deal Professor Chomsky outlines—one which would involve Russia giving up most of its original war aims.

Remember Putin’s outrageous claim that he was out to “demilitarize and denazify” Ukraine? It’s hard to see what would count as achieving that short of outright regime change in Kyiv.

Many Americans are convinced that Putin will never accept anything short of such a total victory and that, as such, there’s no point in pushing for a diplomatic solution. All I can say to that is that we won’t know if we don’t try.

Diplomacy can be messy and demoralizing. Peace negotiations rarely result in anything close to perfect justice. But the alternative is—at best—an enormous amount of avoidable human suffering and at worst the end of human civilization. Let’s give peace a chance.