Out of the squalid greed of the Madoff mess emerges a Wall Street whiz of actual noble spirit whose testimony is forcing the owners of the Mets baseball team to relinquish as much as $83 million they received from the mega-crook.

The noble whiz’s name is Noreen Harrington, and she learned the ethics of Main Street while being raised by the suddenly widowed mother of four young daughters. Years before she contemplated taking a witness stand, she occupied a lifeguard stand on Long Island.

“In those days when I blew my whistle, it was to save somebody’s life,” Noreen Harrington once observed.

She had gone on to become another kind of whistle-blower on Wall Street, alerting then–New York Attorney General Eliot Spitzer in 2003 to what became a widely publicized mutual-fund scandal. She later said she had been spurred to say something after she witnessed her Main Street sister’s anguish over her dwindling 401(k) savings. She was quoted saying that losing a cousin and 13 close friends on 9/11 had further sharpened her sense that “life is short and you’d better live it right.”

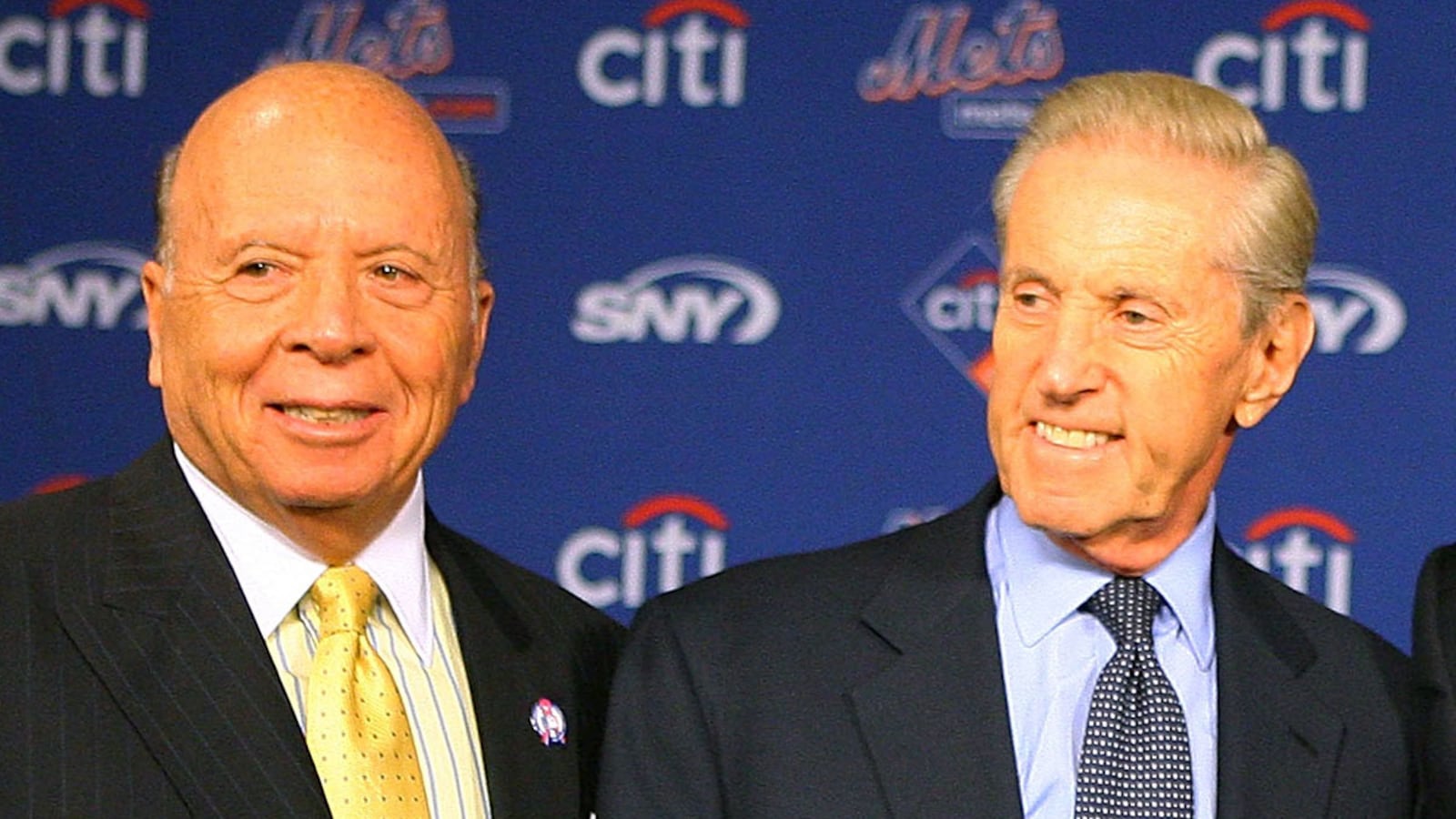

But the mutual-fund tip-off was unrelated to the testimony that proved so expensive to Mets owners Fred Wilpon and Saul Katz on Monday. This more recent case is a civil lawsuit in which the trustee in the Bernie Madoff case is seeking to recoup millions in bogus profits that the Mets owners raked in, in the upper regions of the pyramid scheme.

The trustee is maintaining that Wilpon and Katz should have known that Madoff was a crook. Manhattan Federal Judge Jed Rakoff ruled that the trustee needed to prove the Mets owners had demonstrated “willful blindness.” Rakoff seemed poised to throw out the case.

Then the judge read the deposition the 54-year-old Harrington gave on Dec. 30, 2011 regarding her brief time as chief investment officer of SP Capital, a hedge fund connected to Wilpon and Katz. Harrington testified about a meeting in the summer of 2003 during which she offered Katz her expert opinion of the unvaryingly positive returns reported by Madoff and a crony named Ezra Merkin.

“They were too good,” Harrington recalled saying more than five years before Madoff’s arrest. “They were too good to be true.”

She had started her career at Goldman Sachs, and in her 11 years there her mentors had included world-class financial geniuses such as Fischer Black, whose results never equaled Madoff’s. She testified that she told Katz that Madoff’s improbable results could be explained by illegal trading.

“I said, if it wasn’t that, I believed it was fiction,” Harrington testified. “He said, ‘What do you mean by fiction?’ And I said, ‘I don’t believe the numbers are worth the paper they’re written on.’”

She recalled that Katz was “visibly angry” and said something biting about her “having all the answers.”

“And I said to him, you know, quite to the contrary, I don’t have enough answers,” she testified.

She remembered telling Katz that she had been wrong before and was willing to consider she might be wrong again. She suggested they meet with Madoff and go over the numbers.

“You know, one of the things that I’ve relied on in my past, in my career, is numbers don’t often lie,” she testified. “ People can. And so I’m generally more comfortable with math.”

Wall Street did not sound so different from Main Street, as she added, “We have an obligation to our investors to do the work. We charge a pretty hefty fee.”

And she said that besides going over Madoff’s numbers, doing the work meant, “I know that we would want to meet with his traders, that we would want to actually maybe even sit with them, see them, see them trading.”

The lawyer for the plaintiff inquired, “Did Saul Katz respond in any way when you asked for the meeting with Madoff.”

“He did not,” Harrington replied.

“And did you get a meeting with Bernie Madoff’” the lawyer asked.

“I did not,” Harrington said.

She testified that not long afterwards, her immediate boss had informed her that the fund was going to invest in Madoff-Merkin without performing what she considered “due diligence.” She recounted her response.

“Then you will have to go ahead without me.”

She immediately resigned.

“If we forgo the process, then we have lied to your investors and we haven’t done the work we were hired to do and I will not do that,” she explained in the deposition.

Her prior experience as a Wall Street whistle-blower had not left her desirous of more tumultuous press attention. But had she ever been able to do the math and confirmed her suspicions about Madoff, she remains enough of a lifeguard that she certainly would have blown the whistle again rather than let people continue being hurt.

Her 2011 deposition did become part of the record of Picard v. Mets Ltd. Partnership, which grew so voluminous that Judge Raskoff began a Feb. 23 hearing by telling the lawyers, “Although my law clerk is well over six foot tall and weighs nearly 200 pounds, he was not able to bring up to the courtroom the immense amount of briefing and summary judgment materials that you have favored the court with.”

The one document the judge asked his clerk to retrieve was the Harrington deposition. Raskoff read aloud the pages in which she described her meeting about Madoff. Raskoff then asked the lawyer for the Mets partners to explain why Katz had grown immediately angry at Harrington’s suggestion that the returns were “fiction.”

“I think he trusted Mr. Madoff and he did not like what she was saying and didn’t believe what she was saying and got angry about it,” the lawyer said.

“Could not a reasonable juror say [Katz] was concerned that she was onto what deep in his heart he feared might be the situation and he, having chosen to blind himself to it, wasn’t happy when she raised it?” the judge asked. “He gets angry immediately, even before he asks her for an explanation.”

The judge then inquired if Katz was asked about the matter in his deposition.

“He was asked about the conversation and he does not remember it,” the defendant’s lawyer said.

The judge noted that in Harrington’s testimony, Katz did not even respond when she asked for a meeting with Madoff.

“This is significant,” the judge noted.

The judge promised to rule by March 5 whether the case could go ahead or be dismissed, as the Mets owners asked. He ended by saying he had a meeting of his own.

“My actually very sweet, long-suffering wife wants me to take her dancing, and I think that’s a good idea,” the judge said.

Nobody should be surprised that a judge of such sentiment paid close attention to the testimony of a witness such as Harrington. He did not mention her directly in the four-page decision he issued on Monday as promised, but the impact was clear as he ruled that the Mets owners would have to pay back as much as $83 million to the victims at the bottom of Madoff’s pyramid. The precise number will depend on how much in “fictitious profits” the trustee can demonstrate Wilpon and Katz pocketed as “net winners” in their dealings with Madoff.

The judge set a March 19 trial date on the issue of whether the Mets partner should fork over an additional $303 million for being “willfully blind” to Madoff’s crimes. The judge said, “The Court remains skeptical that the trustee can ultimately rebut the defendants’ show of good faith, let alone impute bad faith to all the defendants.”

Then the judge went on to say, “Nevertheless, there remains a residue of factual assertions from which a jury could infer either good or bad faith depending on which assertions are credited.”

The most damning and credible of those assertions are the ones made by the former lifeguard who used to blow her whistle to save somebody’s life. Harrington also was once a nationally ranked swimmer, which must have given special meaning to her encounter with Michael Phelps at her alma mater, Adelphi University, in 2008. She stood next to Phelps for a photo as a champion of another kind, one of the 1 percent who never lost the values of the 99 percent.

This manifestly decent woman who says in her deposition, “I rather like numbers,” seems sure to add up to 100 percent convincing later this month, as she goes from lifeguard stand to witness stand.