When the El Paso shooter took up arms against defenseless Walmart shoppers this week, he was doing so to stop a mythical "cultural and ethnic replacement brought on by an invasion." The “invasion” rhetoric was straight out of a white nationalist fever swamp and President Donald Trump’s own rhetoric on immigration.

But Trump is hardly the only elected Republican to characterize immigration as a menacing “invasion” by a hostile foreign enemy. Since Trump first took office, Republican congressman have used the same language to demonize immigrants in public debates and in Facebook ads. Sometimes, they do it directly on the House floor.

As recently as June, Rep. Louie Gohmert (R-TX) took to the floor of Congress to use the 75th anniversary of the D-Day landings as an occasion to compare immigrants to an invading army.

“Having done so much contemplation about the 150,000 or so who invaded Nazi-occupied France in 1944, heck, we had virtually that in 1 month,” the Texas Republican said. “They didn't all come to shore with weapons, but it is an invasion when that many people are trying successfully to come into your country."

The invasion framework is attributable in part to President Trump’s 2016 and 2018 midterm election strategy to demonize migrants, particularly after a caravan of Central Americans announced their intention to travel to the U.S. border to seek asylum in the U.S. It’s not against the law for migrants to apply for asylum at ports of entry, but Trump used the occasion to paint the caravan as a menacing army set to break into and occupy America.

“No nation can allow its borders to be overrun. And that's an invasion. I don't care what they say. I don't care what the fake media says. That's an invasion of our country,” Trump said of the caravan at a midterm rally in Tennessee.

Republicans took the “invasion” language and ran with it. In Senate debates in Ohio, West Virginia, Pennsylvania, and New York, moderators pressed Republicans challenging Democratic incumbents on whether they agreed with Trump’s immigration focus and his language characterizing the caravan. Some punted on the question. But others, like now former Pennsylvania Congressman Lou Barletta, leaned into the framing and described the caravan as an “invasion” that’s “growing every day.”

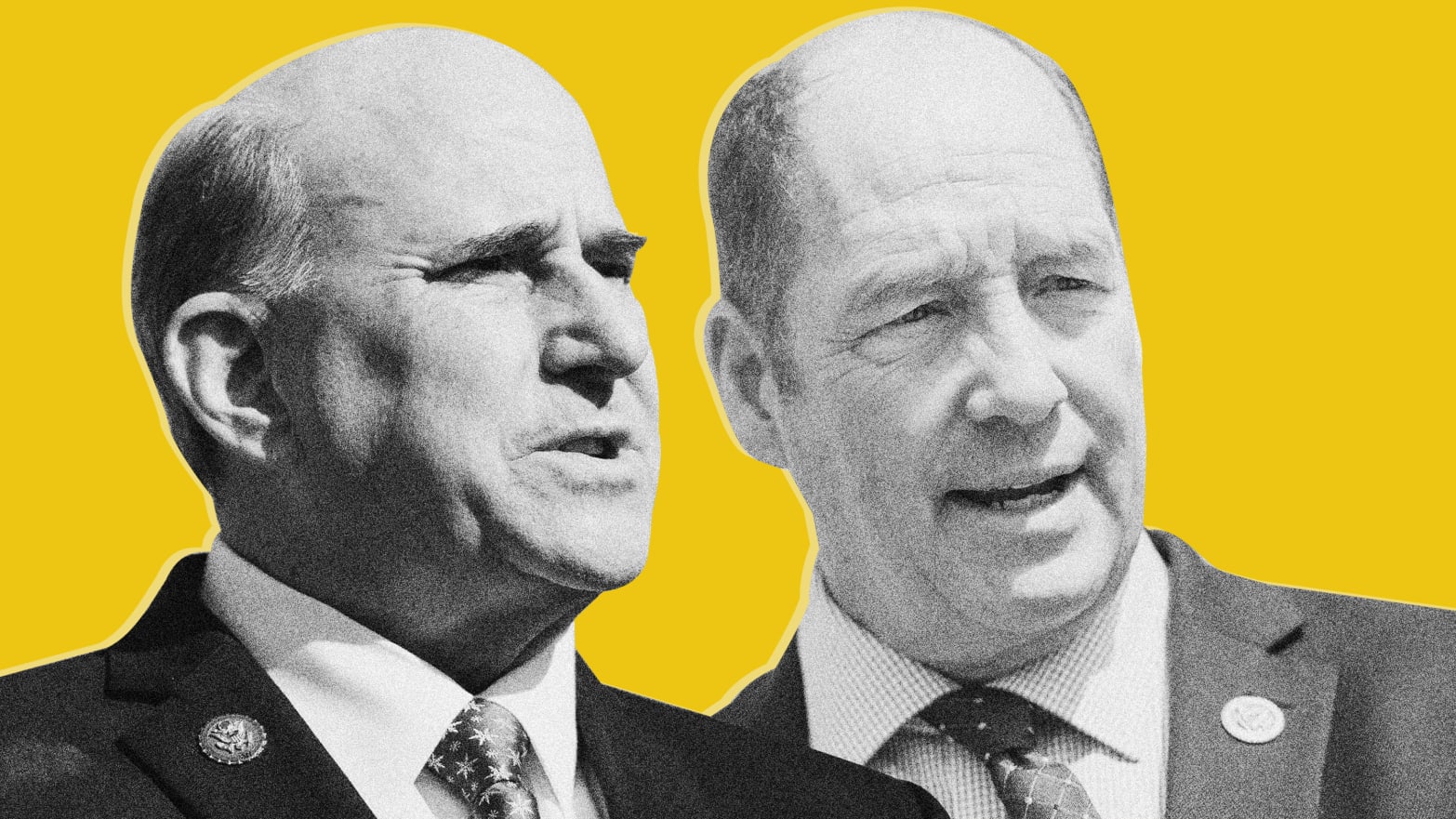

Rep. Pete Sessions (R-TX) even used the talking point in campaign ads. Sessions’ campaign committee paid for Facebook ads highlighting a Daily Caller article in which a Customs and Border Protection union official called the caravan an invasion. “If you agree we need to stop these lawless acts against our nation…go vote EARLY and go vote TODAY!” The ad, targeted primarily at men over the age of 55, ran on Facebook in the week before the election and was seen by under a thousand viewers.

The martial language wasn’t only a byproduct of a midterm strategy but one with deeper roots in Republican rhetoric. Trump himself used the term “invasion” to describe immigration from Latin American countries before he took office. As early as 2015, he quote-tweeted a follower who complained about the "invasion of millions of illegals tking [sic] over America!" and his embrace of the term continued up until weeks before the El Paso attack, when he demanded in early June that Mexico “stop the invasion of our Country by Drug Dealers, Cartels, Human Traffickers…Coyotes and Illegal Immigrants.”

When Rep. Ted Yoho (R-FL) proclaimed that “Immigration without assimilation is an invasion” on the House floor in February 2018, it sounded like just another pivot off of the president’s talking points. But the line—and the idea that even legal immigration is an existential threat to the U.S.—predated Trump’s own presidency. Bobby Jindal used the talking point verbatim in a 2015 presidential debate to contrast his conservative bona fides with former Florida governor Jeb Bush’s relative moderation on immigration.

“We must insist on assimilation. Immigration without assimilation is an invasion. We need to tell folks who want to come here to come here legally,” said Jindal. “Learn English, adopt our values, roll up your sleeves, and get to work.”

Republican congressmen have continued to riff off of the “invasion” language even long after the caravans passed. In December 2018 floor speech, “Why Our Borders Matter,” Rep. Tom McClintock of California harped that the caravan wasn’t really a caravan but a military threat.

“An invasion is a group of people attempting to violate a nation's border by force, whether by military or mob action,” he said. “The vast majority camped on our southern border are military-aged males.”

Trump’s declaration of an “emergency” at the border offered Republican congressmen like Texas’ Jodey Arrington another chance to cast immigrants as an enemy army. As Trump prepared to divert resources from the military to the border, Arrington said in a House speech that the primary constitutional responsibility of the government was to “protect every State in the Union against invasion” and that the U.S. had “abdicated” that responsibility on immigration.

President Trump appears to view the “invasion” framework as a political winner, as well. The New York Times reported that his reelection campaign has run 2,000 Facebook ads since January using the word “invasion” to describe immigration to the United States.

What’s less clear is whether Trump will drop the word from his rhetoric in future public appearances. In a speech on Monday about the shooting in El Paso and a separate mass shooting in Dayton, Ohio, the president referenced mental health, violent video games, and the internet as potential radicalizing forces for domestic terrorists like the El Paso shooter. What he did not mention was inflammatory political rhetoric or a signal that he might reconsider his own.