Pop quiz: Whose website laments that in the United States today we have “more than one million nonviolent offenders fill[ing] the nation’s prisons,” and sings the praises of “community supervision alternatives such as probation and parole, which cost less and could have better reduced recidivism among non-violent offenders”?

Guess before you click.

It’s not some bleeding-heart think tank, but Right On Crime, a prominent group of conservatives who have aggressively championed criminal-justice reform efforts over the last two years by stressing that a true conservative needs to be not merely tough on crime but also “tough on criminal justice spending.”

The group’s very existence spotlights a new reality in the politics of crime and punishment in America. The conventional wisdom is that if you want to see our bloated, dysfunctional, unprecedentedly large criminal-justice system fixed, come November you should vote for Barack Obama. But given policy and practical developments of recent years, there’s a good argument to be made that a President Romney could prove to be more likely to make real and long-term reforms to American criminal justice.

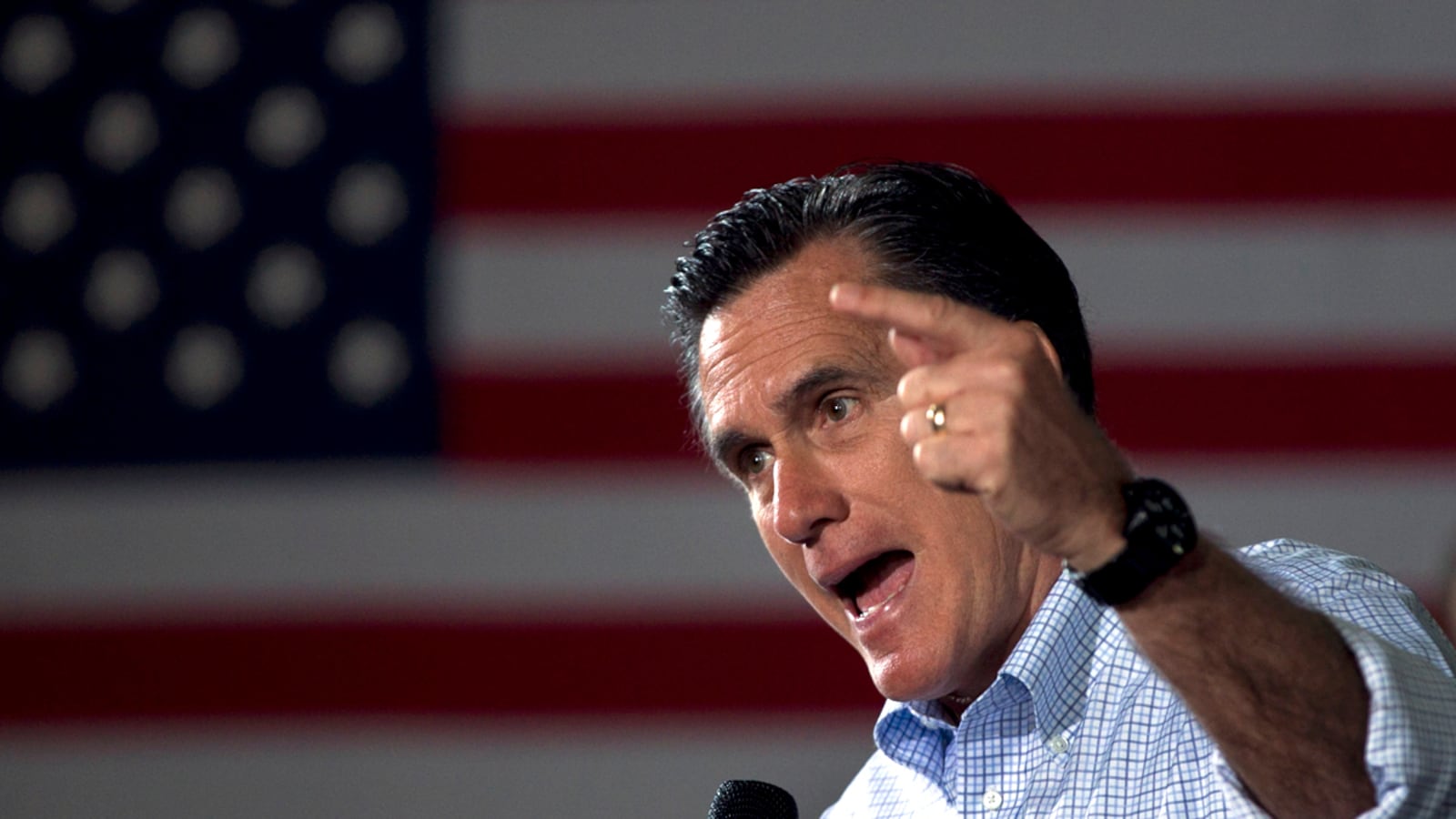

Romney—now all but certain to secure the GOP presidential nomination—steps onto the national stage at a dynamic time for conservatives and crime.

For decades, it has been an article of faith on both sides of the aisle that winning candidates are the ones who promote the most punitive criminal laws possible. Especially since the 1988 presidential campaign, when George H.W. Bush successfully damaged Michael Dukakis by portraying him as “soft on crime,” national and local politicians have consistently aspired to appear tougher on criminals than their rivals.

Predictably, as political rhetoric becomes legislative reality, the size and reach of our criminal-justice system has grown exponentially over the last three decades, and America’s prison population has increased to levels unmatched in human history. Because prison costs are substantial, this epic growth has had a profound fiscal impact: state and federal spending on corrections has spiked nearly 500 percent over the past quarter century; one of every eight full-time state-government employees now works in corrections.

As state budgets buckle under these costs, Republican governors in traditionally red states, from Alabama to South Carolina to Texas to Ohio, have engineered major criminal-justice reforms designed to reduce prison populations and associated expenses.

Right On Crime fully supports these developments. The group’s statement of principles—which have been embraced by GOP stalwarts from Jeb Bush to Newt Gingrich to Grover Norquist to Ralph Reed—stress that excessive reliance on incarceration is not a cost-effective approach to public safety.

But Right On Crime’s themes should also sound familiar to anyone who was following a longshot candidate named Barack Obama back in 2007. In a major policy speech at Howard University’s Convocation in September of that year, then-senator Obama proclaimed that it was “time to seek a new dawn of justice in America,” and that our society needed to be “smarter on crime and reduce the blind and counterproductive warehousing of non-violent offenders.”

That speech—along with pre-campaign comments by Obama opposing mandatory-minimum sentences and suggesting that the so-called “war on drugs” was not a winning strategy—prompted many who work on criminal-justice issues (myself included) to hope that a President Obama might be an effective advocate for needed reforms.

But criminal-justice reform advocates have been consistently disappointed by the Obama administration’s failure of leadership and vision in this critical area. On nearly every major criminal-justice issue, ranging from federal marijuana policy to criminal discovery reform to mandatory-minimum sentencing to “drug war” funding priorities to clemency practices, even the most ardent Obama supporters have to view his first term as, at best, a missed opportunity to pioneer long-needed reforms.

Even its one arguable success—helping prod Congress to finally reduce the extreme disparities between sentences for crack and powder cocaine—was far more limited than it could have been, mainly due to the administration’s relatively tepid advocacy.

Perhaps those hoping for a lot more hope and change on this front were naive. At least since Dukakis, Democrats have been obsessively concerned about appearing soft on crime. And given the social and racial reverberations surrounding the nation’s first African-American president, one can readily understand why President Obama in particular has fallen so far short of the vision of Candidate Obama.

But this very reality suggests there may be a real opening for Romney on this issue. Without having to do any major Etch a Sketching, Romney could embrace what Right On Crime calls the “conservative case” for criminal-justice reform, and in doing so appeal to groups of independent and minority voters (especially young ones) while demonstrating a true commitment to some core conservative values about the evils of big government.

For starters, there’s ROC’s general assertion that the conservative commitment to “constitutionally limited government, transparency, individual liberty, personal responsibility, and free enterprise” needs to be applied to America’s criminal-justice systems.

A conservative politician with true conviction on these issues could further argue that federal and state governments ought to rely far less on incarceration as a response to less serious crimes, or that the long-running “war or drugs” (which surely restricts individual liberty, personal responsibility, and free enterprise as much as alcohol prohibition did a century ago) suffers from many of the same big-government flaws as other top-down efforts to improve society.

Of course, it may be not only naive but even foolish to expect Romney to pioneer change in this arena. After all, he has not yet shown much boldness in his campaign strategies so far, and I wonder if he has either the political courage or the personal convictions needed to reshape the GOP message on crime and punishment for the better. Indeed, when Romney was governor of Massachusetts, he took heat from both the left and the right when he tried to develop a “foolproof” death-penalty system for the state. That experience, together with the knee-jerk tough-on-crime stance most politicians still readily embrace, may ensure that Romney will see more political risks than rewards on this path.

But there’s a “toe in the water” opportunity here, provided last summer by none other than Ron Paul. Together with outgoing Massachusetts Democrat Barney Frank, Paul introduced a bill that, while allowing the federal government to continue enforcing interstate marijuana smuggling, would let states develop and apply their own distinct laws on marijuana production and use so that individuals could grow and sell it in places that choose to make it legal.

If Romney were to express his support for this bill, he might not only pull in libertarian-leaning independents who have helped fuel the Paul campaign, but he would signal to minority groups—who rightly lament the disparate impact of the drug war on people of color—that he understands and respects their concerns. Further, if Romney adopted this sort of “states’ rights” approach to marijuana laws and regulations, he could reinforce and reiterate the nuanced principles behind his claims in the health-care-reform debate that there are some areas where the federal government ought to butt out.

But Romney’s apparent lack of conviction isn’t his only obstacle. In the last few election cycles, traditional criminal-justice issues have not been a topic of much discussion, perhaps because of recent declines in the crime rate and because, post-September 11, voters seem to care more about how candidates view the war on terror than how they view the war on drugs. Tellingly, Romney’s official campaign website has an Issues page with detailed positions on two dozen topics, none of which address traditional crime and punishment concerns. Yet that same page asserts that the “foundations of our nation’s strength are a love of liberty and a pioneering spirit of innovation and creativity,” and another page champions a “simpler, smaller, smarter government” and asserts that “as president, Mitt Romney will ask a simple question about every federal program: is it so important, so critical, that it is worth borrowing money from China to pay for it?”

The important recent work of many Republican governors on sentencing reform, as well as the existence of prominent conservatives supporting the Right On Crime movement, indicate that many on the right would support and even help champion a commitment to reconsider the efficacy of drug war and to question which parts of the massive federal criminal-justice system are not worth the cost. Perhaps with prodding from those on both sides of the aisle, this election could bring us more real talk about criminal-justice reform from candidate Romney than from President Obama.