A lot of video games have a character problem, mostly in that they don’t really have characters as such. The first season of the Paramount+ Halo show tried to overcome this (pretty substantial) obstacle in adapting the long-running Xbox shooter series by taking the mask off of its protagonist, Master Chief—a supersoldier best known to players for the iconic green slab of a helmet that eternally hides his face.

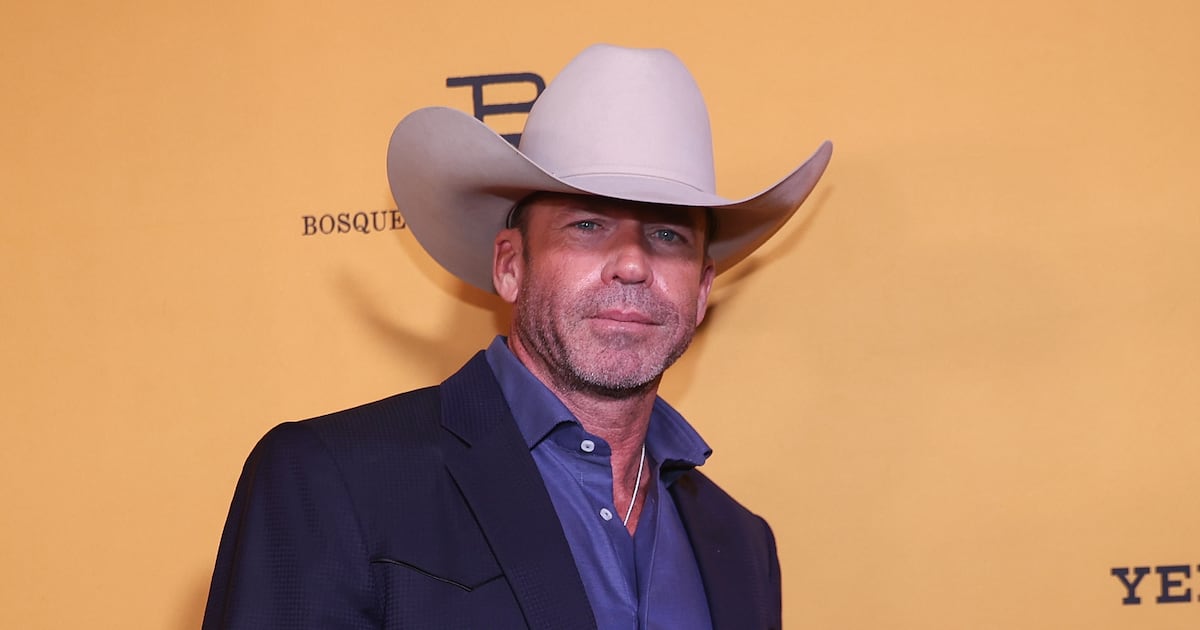

The result was a depiction of the character, buoyed by a committed performance by Pablo Schreiber, that turned out to be more captivating than the plot around him. Schreiber’s version of Master Chief was, at times, as stern and stoic as his digital counterpart and, at others, animated by a trembling arc of self-discovery whose emotional force seemed to unnerve and exhilarate him by turns.

Still, as successful as Halo’s first season was at turning Master Chief into a compelling, distinctly human character, it was also surprisingly talky and sober, and a bit too abashed of its hyperactive video game origins to ever feel like a total success as either a science fiction drama or an action series. Halo’s second season (premiering Feb. 8) initially seems to have solved this problem by leaning into spectacle. Its first episode, “Sanctuary,” kicks off with a straightforward and tense sequence: Master Chief and his fellow Spartans evacuating a planet’s population before a malevolent alien force called the Covenant blow the whole place up.

Rather than try to capture the freneticism of a video game firefight in the chaos that follows, Halo tinges its first several action scenes with horror. Hulking Covenant aliens spring out of clouds of noxious fog or emerge from the darkness of shadowy tunnels with monster-movie menace, ripping hapless marines and civilians limb from limb. As in the first season, it’s the violence that gives these potentially weightless CGI creatures heft. Master Chief snaps an alien’s neck with a branch-breaking crack. Gouts of blood splatter from gunshots and plunged knives. The sound of thudding boots and bodies smacking against the ground is suitably impactful, grounding the digital effects with earthy muck and generous gore.

These action scenes possess a visual flair borrowed, in part, from the source material. Halo can be, at times, a very good-looking show, its establishing shots of invented planets and futuristic megacities capturing the alternately grim and inspiring future envisioned by a franchise where space marines traipse across technicolor galaxies. In one scene, alien warships rise from a sea of clouds like breaching whales. In another, we’re shown what “plasma burns” look like on a body shot dead by Covenant guns.

Unfortunately, as in the first season, these kinds of scenes often take a backseat to inert, meandering small-scale drama. The first four episodes made available for review include a B-plot surrounding revenge-seeking orphan Kwan Ha (Yerin Ha) that doesn’t really cohere with Master Chief’s story. The dialogue can be dull and expository, though it’s sometimes elevated by the actors, including Bokeem Woodbine, reprising his role as former super-soldier- turned-outlaw-leader Soren-066.

Too often, Halo pulls focus from the immediate stakes of the human/alien war to dwell instead on rote melodrama. Schreiber’s Master Chief is as interesting as before. So is Natascha McElhone’s Dr. Halsey, a Frankenstein figure who can’t help but appear delighted with the ethically dubious results of her mad science projects. But other major characters, like the wormy bureaucrat James Ackerson (Joseph Morgan), don’t earn their screen time.

Beyond the disjointed plotting, Halo possesses a hard-to-ignore militarist subtext that comes into clarity as Master Chief continues to search for selfhood. In the second season, we’re shown duplicitous bureaucrats who override the first-hand knowledge of heroic military figures to disastrous effect, the Spartans hampered by red tape in their efforts to save lives and counter a vicious enemy. As Master Chief and his genetically engineered squad struggle to experience new emotions, like joy and empathy, the show points out that these feelings lessen their effectiveness in battle. The soldier, Halo suggests, is the figure best suited to lead society in times of peril.

The show may motion toward a general anti-war sentiment—a captain hopes aloud for a future where humanity will be free of war’s horrors; civilians caught up in battle are depicted as tragic figures—but these small moments are overshadowed by a larger tribute to heroic soldiering free of government oversight and the transformative power of individual might.

Halo works well when it’s willing to be goofy, and stumbles when it gets serious. At its best, the show strikes a balance between colorful, fantastical action spectacle and smaller-scale character work; there are moments in the first half of the new season that successfully draw stray plot threads into the main thrust of the story and more enthusiastically lean into silliness. For now, though, Halo, like its identity-seeking protagonist, is still trying to find itself.