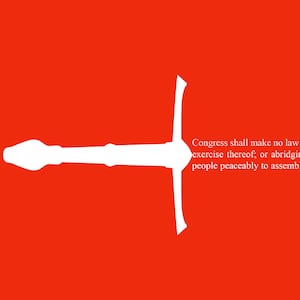

I’ve practiced First Amendment law for more than a decade—first in Washington, D.C., and now in New York. I’ve represented newspapers from New York to Australia. I teach media law at Fordham Law School and regularly publish scholarship on the history of the First Amendment.

I believe deeply in that amendment and in the historical role of newspapers as a bulwark against intrusions on the rights protected by it.

So I was surprised to see my local New Jersey newspaper, The Westfield Leader, argue that some speech with which it disagrees is not “free speech.” The editorial, “Free Speech Does Not Include Freedom to Incite Violence,” takes a familiar and unfortunate form: “I believe in free speech, but…”

This small-town controversy centers on the local school board and one member in particular, Sahar Aziz, but has its roots in the Israel-Hamas war a world away. Ms. Aziz is a law professor at Rutgers Law School where she researches the intersection of national security, religion, and civil rights. She is also an outspoken critic of Israel’s military response to the Oct. 7 Hamas attacks.

She has been criticized for employing the controversial (if disputed) phrase, “from the river to the sea,” and for her commentary on X (formerly Twitter), including writing: “People all over my town in New Jersey are posting ‘I Stand With Israel’ signs on their lawns. I read them as ‘I Stand With Israel’s #genocide of #Palestinians.’”

As a result of her speech, she has been targeted with multiple petitions (one signed by nearly 5,000 people) demanding that she resign or be removed from the school board. Last week, even The Westfield Leader joined the fight against Ms. Aziz. But rather than engage in counter speech or contest her ideas on the merits, the newspaper argued that her speech is not even free speech.

Under the First Amendment, we are to expect, in the words of the U.S. Supreme Court, that “debate on public issues should be uninhibited, robust, and wide-open, and that it may well include vehement, caustic, and sometimes unpleasantly sharp attacks.” Unsurprisingly, in a country of hundreds of millions, we’re not all going to agree with what each other says but by and large we get to say what we want.

Pro-Palestinian activists protest outside the New York Public Library for a cease-fire in Gaza, on Nov. 17, 2023 in New York City.

Eduardo Munoz Alvarez/VIEWpress/Getty ImagesFor example, the newspaper has the right to lob ad hominem attacks at Ms. Aziz, such as calling her a “supposed scholar,” and even to lean on overwrought hyperbole such as, “Ms. Aziz is a disappointment at every level.” The newspaper has the right to criticize Ms. Aziz and her speech, too, especially because Ms. Aziz is a public official.

But, in this country, while it’s cliche, we protect the right to express speech—even the varieties we hate.

At its most basic, we protect this kind of speech out of naked self-interest. While you might be the one drawing lines around others’ speech today, someone else might be drawing lines around your speech in the future. So we shouldn’t be in the business of drawing new lines to begin with.

We have seen this play out recently. The right defends its myriad bans on books by arguing that they are sexualizing children. This is, to an extent, the same moral basis that the left has also proposed banning books it viewed as racist. Both sides claim to be protecting children from dangerous ideas, but as one commentator said, “Liberals can’t rebut book bans if they are banning books themselves.”

This failure of foresight has had staggering consequences throughout history.

As scholar (and Daily Beast contributor) Jacob Mchangama pointed out, Weimar Germany once broadly protected free speech but adopted “increasingly drastic measures to combat radical agitation” throughout the 1920s. These laws were intended to save democracy from the likes of Hitler, but ultimately they were weaponized by the Nazis to ascend to and maintain power by controlling speech.

Just as many on the left have conflated offensive speech with violence, and demanded sanctions on its speakers, characterizing Ms. Aziz’s speech as “not free speech” at all ignores these lessons of history—and does so at the left’s own peril. As with book bans, by claiming the authority to police Ms. Aziz's speech, the left is ceding the moral authority to oppose its speech being policed.

Undeterred, the newspaper’s editorial board says (as most do when they are trying to justify limiting speech they do not like) that Ms. Aziz’s right to “free speech does not mean that you can yell ‘fire’ in a crowded movie theater.”

Pro-Israel supporters during the "March for Israel" held on the National Mall.

Michael Nigro/Pacific Press/LightRocket via Getty ImagesBut that is not a legal test and never has been — it is an aside made by Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes in Schenck v. United States, a case that sent two socialists to jail for months for the “crime” of trying to convince young men to resist the draft. It is also not even an accurate retelling of that aside, which spoke only of “falsely” yelling fire in a crowded theater. At any rate, there are plenty of reasons one might have for yelling “Fire!” in the first place.

Holmes also later disclaimed Schenck and admitted that he had been “simply ignorant.” He, along with Justice Louis Brandeis, began penning dissents in support of free speech. And, it was those dissents—what we now call the “Great Dissents”—that define the reaches of the First Amendment today. As Holmes wrote in one, “when men have realized that time has upset many fighting faiths, they may come to believe… that the ultimate good desired is better reached by free trade in ideas.”

Nor does the newspaper characterizing Ms. Aziz’s statements as an incitement to violence change the calculus. Ms. Aziz’s statements are not an incitement to violence as that term is understood at law. That test requires that the speech be “directed to inciting or producing imminent lawless action,” and “is likely to incite or produce such action.”

This is a remarkably high bar, the most speech-protective principle in the world. We should be proud of that distinction.

Ms. Aziz’s comments also are not transformed into incitement merely because they inflame others or inflict severe emotional harm on them. Were that the case, anyone’s offense (however deep and earnest) at another’s speech would be grounds to shut down speech we don’t like.

But in this country we reject that idea. As the Supreme Court wrote, “A function of free speech under our system of government is to invite dispute. It may indeed best serve its high purpose when it induces a condition of unrest, creates dissatisfaction with conditions as they are, or even stirs people to anger.”

Relatedly, the newspaper suggests that Ms. Aziz’s speech is not free speech because it is “hate speech” that is not “peaceable.” But once again, characterizing speech as something nefarious sounding does not render it unprotected.

In fact, “hate speech” is protected by the First Amendment. We don’t protect hate speech because we think it adds much (if anything at all) to the marketplace of ideas that Holmes wrote about. We protect it, as I said earlier, because we don’t have a choice.

Again, history holds the lesson. In the 1970s, the village of Skokie, Illinois —home to a large number of Holocaust survivors—went to court to get an injunction preventing the local Nazi party from holding a march downtown. David Goldberger, an ACLU lawyer, came to the Nazis defense and convinced the Supreme Court to stay the injunction.

Goldberger, who is Jewish, later wrote of his decision to take the case on behalf of the Nazi party: “the power to censor Nazis includes the power to censor protesters of all stripes.” In Skokie’s war on the Nazis, Goldberger saw echoes of “efforts of Southern segregationist communities to enjoin civil rights marches led by Martin Luther King during the 1960s.”

Tolerating what one might view as hate speech also serves other fundamental roles. It guards against incubated violence. Silenced speakers do not disappear. They are just pushed underground where, under more and more pressure, they might burst out into the public not with speech but violence.

As Salman Rushdie—a writer forced to live in hiding for years and who barely survived an assassination attempt by an individual that was convinced that one of Rushdie’s books constituted an act of violence on his religion—recently warned to an audience at the National Constitution Center, tolerance (not approval) of hate speech prevents the “glamor of taboo” that accompanies the criminalization of speech and ideas.

It was Hitler, Mchangama reminds us, that used attempts to silence him as “fodder for fruitful propaganda” that included posters depicting him muzzled “as a martyr unfairly singled out.”

And, finally, permitting “hate speech” serves a baser human function. As Holocaust survivors thankful for Mr. Goldberger’s defense of the Nazis’ right to march in Skokie told him, “they did not want the Nazis driven underground by speech-repressive laws… They wanted to be able to see their enemies in plain sight so they would know who they were.”

Argue against Ms. Aziz’s ideas and others like them on the merits if you disagree with them, if you find them loathsome. But don’t argue that she or others with whom you disagree have no right to express their ideas in the first place. That is a dangerous and un-American path.