On the corner of Yonge Street and Asquith Avenue in Toronto is a rust-colored brick ziggurat. Each window-covered floor is terraced, receding further backwards as it moves upwards. It’s also a pattern that repeats from the back of the building. This is the Toronto Reference Library (TRL) and it is the latest selection for our monthly series, The World’s Most Beautiful Libraries.

I was in the city to visit the TRL, a building I’d only seen in photos, but always thought was stunning. While I found that perception to be justified, I also encountered something else on the inside: a democratization of space. Behind the library, as I later learned, is the philosophy of its architect, Raymond Moriyama—whose perspective on design was forged when he was a child living in one of Canada’s Japanese internment camps.

Toronto Reference Library, exterior.

Toronto Public LibraryThe Toronto Reference Library was commissioned in 1971 to replace the original and limited Metropolitan Toronto Library. Moriyama’s original plans in 1973 were considered too expensive ($30 million CAD) and the footprint of a new building too big. The shape was also square and all glass, which many didn’t like. A new design, as it appears today, was approved in 1974 and used the terraced feature to reduce its presence while still bringing in the light.

The library’s atrium is spacious. While the outside of the building recesses inward, the inside of the building flows outward, with each floor above smaller than the one below. Every level of the library has a line of sight to the others. Floors are only divided by white, half-walls, which flow and curve through the building, avoiding any hard corners. Those receding windows I saw outside—and a large skylight above—light up the atrium.

The library also features round-windowed elevators that overlook the atrium. To my eyes, at least, they are reminiscent of the old pneumatic tubes found in a post office. In this case, people instead of mail are delivered to the library’s five floors.

The building was opened in 1977. In a pamphlet written for the library opening, Moriyama acknowledges that the project was a group effort and informed by input from stakeholders. It is also, he says, based on his life experience during World War II. He wanted to create a place of “personal peace,” that fostered “thinking.” Social institutions, he argues, are blind to “the real need of the individual for personal growth.”

“Canada’s aspiration to achieve unity and a unique identity through its policy of multi-culturalism,” wrote Moriyama, “lies not only in mere tolerance and acceptance of diverse ethnic and community groups. It is rooted in positively encouraging self-fulfillment of each individual. To know oneself is to be self-possessed, to be at home in the world. National confidence starts with the individual.”

Moriyama is a phenomenologist, concerned about the direct experience and perspective of the visitor. In this way, the medium of the library becomes the message.

Moriyama was born and raised in Vancouver. In 1942, during World War II, his father—a pacifist—was taken to an internment camp in Ontario for resisting compulsory service: 22,000 Japanese Canadians, 90 percent of them living in British Columbia, were in camps. He and his sisters were left with their mother to run the family business. One Canadian Mountie told him he would be shot if he was found outside. He, his mother, and sisters eventually lost everything, including the family business, and also ended up in an internment camp in British Columbia.

Asian hate spread fast in Canada in the early 20th century, especially due to the influence of the Asiatic Exclusion League, an import from the United States. The League pushed for the exclusion of Asian immigrants, eventually leading to the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1923—also a U.S. import. In a documentary on his life, Magical Imperfection, Moriyama recalls being called “an enemy alien,” adding that “the treatment by the Canadian government during the war will never leave me.”

While in those camps, Moriyama had a life changing experience.

When he was 4, he was severely burned due to an accident in the kitchen. In the camps at 12, he found himself mocked in the showers by his own people due to his significant scarring. He decided to take a risky step and began sneaking out to bathe in the Slocan River. To make sure he wasn’t spotted, he built a platform in the trees from lumberyard scraps he found, and tools he scrounged together.

Moriyama recalls finding peace up there. “This is when I first learned to listen to the Earth,” he wrote for University of Toronto Magazine. “I began to understand that I could not hate my community and my country, or my hate could crush my own heart and imagination. I replaced the despair with ideas about what I could do as an architect to help my community and Canada.”

He then crafted his own guiding principles.

“Architecture,” wrote Moriyama, needs “to be more than nicely proportioned surface treatment. If it is to be truly ‘golden,’ architecture has to be humane and its intent the pursuit of true ideals, of true democracy, of equality and of inclusion of all people.”

As I see it, it is the library’s open floor plan that enables everyone to have their place—and a reference library is the epitome of the democratization of knowledge.

It is easy to see how Moriyama’s design attempts to bring in that peace he found in nature around the river. The original design included a water feature, which was a type of soundscape to block out the street noise. Recently, however, those features were shut down while they work to make them more sustainable.

Toronto Reference Library living wall.

Courtesy of Brandon WithrowSimilarly, the original library came with hanging plants off of each level, which provided a green element and were meant to reflect the hanging gardens of Babylon. They became difficult to manage and the water system wasn’t great for preventing mold, so for a while they were removed. Today, however, there is now a new hydroponics system and the plants have returned. That original nature-scaping of the library is now also clearly alive in a study area that is home to a living wall, whose plants act as a biofilter in the library.

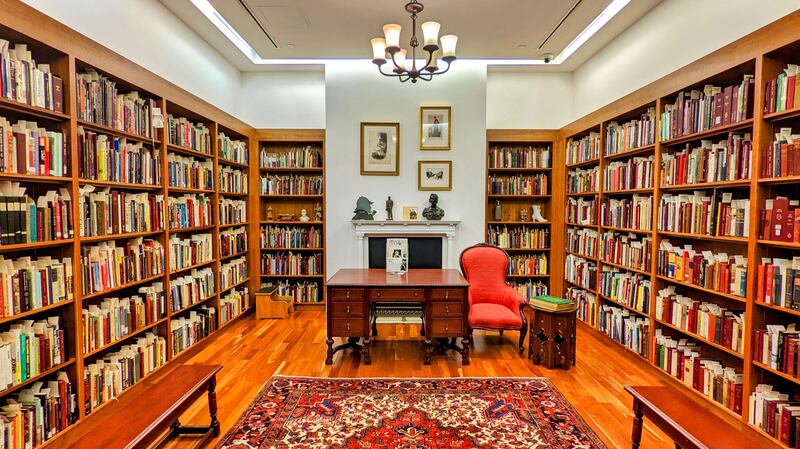

Toronto Reference Library. Arthur Conan Doyle Room.

Courtesy of Brandon WithrowWhen you visit today, there are a lot of new elements to experience at the library, like the inclusion of a fascinating Arthur Conan Doyle Collection, for example. Part of the Marilyn & Charles Baillie Special Collections Centre, the Doyle collection has over 25,000 items related to Sherlock Holmes in a room designed to look like a Holmesian library. The rest of the Baillie Special Collections of rare books and archives is found in a connected clean, white futuristic, glassed-walled room.

Choral collections and newspaper collections ensure that the library is a space for preserving the rare and hard to find pieces from the past, while the glass-walled Digital Innovation Hub and Asquith Press provide maker spaces that empower anyone to create and publish their own work. There are also glass-enclosed study pods. Additions like these are built with glass walls, and, I was told, were designed in concert with Moriyama’s firm.

But the TRL isn’t the only library I came to see.

North York Central Library, the TRL sister library.

Courtesy of Brandon WithrowNot too far away to the north of the Toronto Reference Library is another product of Moriyama’s democratic imagination in the form of the North York Central Library. Designed in 1987 by Moriyama & Teshima Architects, the building itself has no real street presence. One of its entrances is indoors and unassuming, off of what could pass as a mall that is connected to Hotel Novotel and the subway. Once inside, however, it is a different picture and definitely a Moriyama creation, as its floors also have those white half-walls that flow energetically through the building like a river.

The library underwent a renovation and update that was completed in 2019 by the firm Diamond Schmitt. The entrance is marked by a multicultural “frieze from the façade of the former 1959 building on the site by artist Harold Town,” which “depicts six alphabetic symbols from Runic, Roman, Cree, Chinese, Indian, and Semitic languages.” A warm-wide wooden staircase of the atrium leads to more of that democratization—a digital innovation lab, a room for sewing, a recording studio, and a learning space for children.

It is the clear sister to the TRL and the message that Moriyama began there.

The Toronto Reference Library is a building of light meeting metaphorical light. It provides a place for visitors to come and find themselves. They may not know it, but they are benefiting from a tragic part of history that Raymond Moriyama turned into an opportunity for equality—to create both buildings that, as he puts it, gives “dignity to the mind and imagination.”