A few years ago, while ushering a reporter around Beaufort, S.C., the lovely coastal town where he grew up and anchored much of his fiction, Pat Conroy capped the tour with a stop at the town’s military graveyard.

Walking down the rows of uniform tombstones standing at eternal attention, he lingered at two of the markers: his mother’s grave and his father’s. He talked about each of them with almost equal affection, which left a visitor puzzled for a moment. Conroy, after all, had written about both of his parents in his novels and memoirs, and while he always portrayed his mother as long-suffering if not downright saintly, his depictions of his overbearing, brutal, impossibly demanding father verged on the satanic. But the hate with which the son wrote of the father was clearly balanced with an equally fierce, albeit frustrated love, and the fusing of those two emotions was suddenly so obvious in the son as he stood there talking in that graveyard. His quarrel with his father had not ended simply because his father was dead. It was too deep and complicated to be derailed by anything so trivial as death, and the love and hate in the heart of the son were so intertwined as to ensure that the quarreling—with his father but also with himself—would go on as long as Pat Conroy was still breathing. The conflict was what breathed life into his writing, and what kept him going, too.

Being a writer, though, gave Conroy one edge over his old man: the son controlled the narrative, in his books and even here in the sun baked cemetery. For there on Donald Conroy’s headstone were the words “Great Santini,” the nickname Pat Conroy had given the fictional version of his father in the novel of the same name.

It was a nickname—and a portrayal—that the father had first violently rejected and then come to embrace. Near the end of his life, the father had joined the son on book tours where they’d both signed Pat Conroy books for the fans, the father always being sure to remind book buyers that his son wrote fiction, a word he’d underline above his signature.

Still, the name was the son’s creation, and seeing it chiseled there in stone reminded the reporter of a fact ignored at one’s peril: A writer always has the last word.

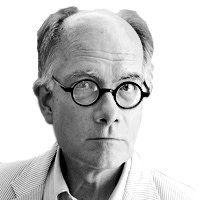

Conroy, who died Friday of pancreatic cancer at 70, was not a vengeful man. But he had a hard time turning loose of hurt. He gnawed it like dog with a bone he’s dug up and buried a dozen times. If there was good fortune in this, it lay in his ability to transmute that hurt, that sense of a scarred past, into words that enchanted millions of readers. And if some of the words in such books as The Great Santini and The Prince of Tides were entirely too purple, that didn’t matter because enough of them had the ring of truth to make the reading worth the trouble.

A military brat, Conroy moved 23 times in his childhood. As an adult, he stayed more or less put, settling finally on Fripp Island, near Hilton Head, where he could walk and swim in the landscape that was the closest he ever had to a permanent home.

The South Carolina coast and particularly the low country around Charleston were both the source of his hurt and his inspiration, and when those two things melded, as they did in his indelible portraits of his violent father—a character who seems even more monstrous in the son’s memoir, A Losing Season, than in Santini—the result was unforgettable.

Traveling up and down that coast with Conroy (a man so bighearted that, when he discovered that the reporter had never seen Mt. Pleasant, the island where the reporter’s mother had taught school after graduating from college, wrenched the car around and detoured just to include a tour of the town and a search for the school), one understood that he needed the past, as embodied in live oaks and sloughs and the pole-axing intoxicant of low tide, the way the rest of us need oxygen. He needed it all, good and bad all jammed together.

It gave him inspiration, along with a sublime sense of satisfaction. Touring the Citadel, South Carolina’s military school where he had attended college, he detoured again to check out the water tower.

"Somebody put my name up there and then painted one of those circles with a slash over it," he said. "I just wanted to see if it was still up there." Conroy had most recently run afoul of the college in the late '90s when he supported the admission of female cadets. The rift was smoothed over so successfully that ex-cadet Conroy was asked to give the 2001 commencement address, and he loved hearing from cadets who told him that reading The Lords of Discipline, his 1980 novel about the Citadel, persuaded them to apply. So why did he care if his name was still defamed on the water tower? "Hey, you got your name on a water tower," he said with a big grin, "you know you're still in the game."

Conroy played basketball for the Citadel, joining as a walk on his freshman year and finishing four years later on the starting five. If the Citadel has any sense, they’ll retire his number. They’ll never see his like again.