As WikiLeaks prepares a new dump of secret war documents, the feds’ intel SWAT team races to do damage control. Philip Shenon reports on its leader and its inner workings.

In a nondescript suite of government offices not far from the Pentagon, nearly 120 intelligence analysts, FBI agents, and others are at work—24 hours a day, seven days a week—on the frontlines of the government’s secret war against WikiLeaks.

Dubbed the WikiLeaks War Room by some of its occupants, the round-the-clock operation is on high alert this month as WikiLeaks and its elusive leader, Julian Assange, threaten to release a second batch of thousands of classified American war logs from Afghanstan. Thousands more leaked documents from another American war zone—Iraq—are also reportedly slated for release by WikiLeaks this fall.

“I do not have time to correct all the lies and distortions that are issued each day by the tabloid press and others who should know better,” Assange said in an email.

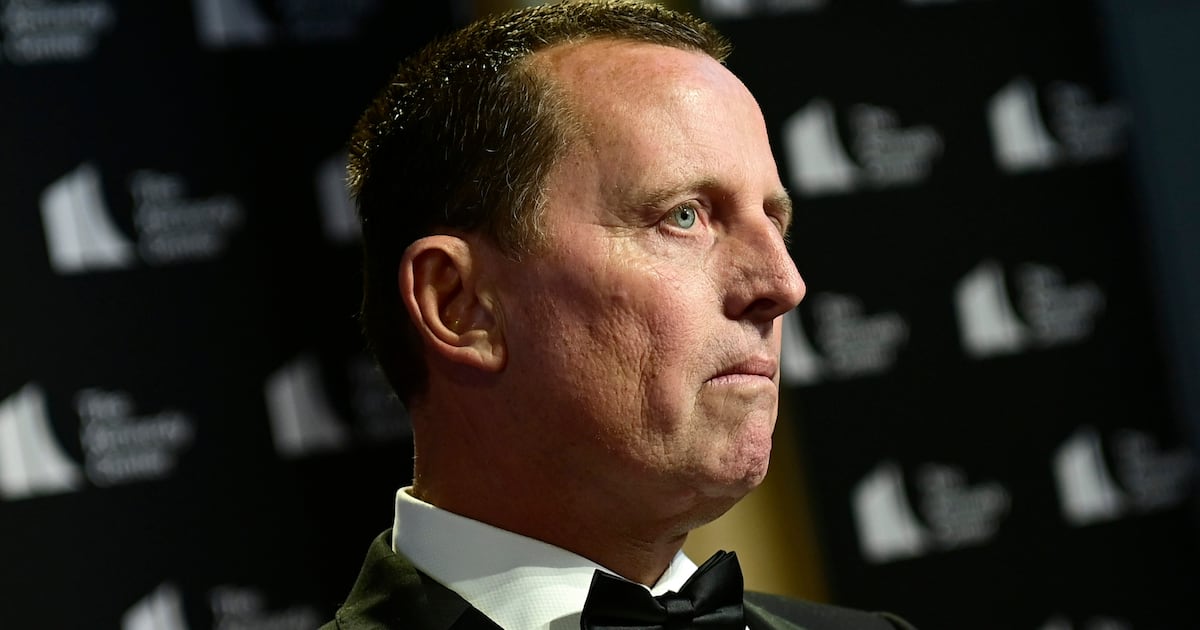

Although outsiders have not been allowed to inspect the “war room” in suburban Virginia and see its staff at work, national-security officials offered details of the operation to The Daily Beast, including the identity of the counterintelligence expert who has been put in charge: Brig. General Robert A. Carr of the Defense Intelligence Agency.

Officials say Carr, handpicked for the assignment by Defense Secretary Robert Gates, is highly respected among his colleagues at DIA, the Pentagon’s equivalent of the CIA, and a fitting adversary to Assange, the nomadic Australian-born computer hacker who founded WikiLeaks and is now believed to be in Sweden.

“I wouldn’t want to go up against General Carr,” a Pentagon official said. “Very smart guy.” Carr served in Afghanistan for much of last year before his transfer to the DIA in Washington, where he runs the Defense Counterintelligence and Human Intelligence Center. In his battle against Assange, officials say, Carr’s central assignment is to try to determine exactly what classified information might have been leaked to WikiLeaks, and then to predict whether its disclosure could endanger American troops in the battlefield, as well as what larger risk it might pose to American foreign policy.

The team has another distinct responsibility: to gather evidence about the workings of WikiLeaks that might someday be used by the Justice Department to prosecute Assange and others on espionage charges.

Carr’s team was given an important head start with the arrest in June of a 23-year-old Army intelligence specialist in Iraq, Bradley Manning of Potomac, Maryland, who is suspected of leaking the Afghan war logs to WikiLeaks and whose computers have been seized.

Lawyers for Manning have suggested that he will plead not guilty when he is formally arraigned.

Assange has not responded in weeks to detailed questions from The Daily Beast, including questions about the sexual-assault allegations he faces in Sweden and reports of internal strife within WikiLeaks.

In an email last week, Assange said, without elaboration, that “I do not have time to correct all the lies and distortions that are issued each day by the tabloid press and others who should know better.”

Officials say that in a sign of the anxiety WikiLeaks has created within the Obama administration, the staff of Carr’s operation, known formally as the Information Review Task Force, has grown by nearly 50 percent since its existence was first revealed by the Pentagon last month.

They said that it includes senior intelligence analysts drawn from throughout the Defense Department, as well as agents and analysts from the FBI.

Marine Colonel David Lapan, a senior Pentagon spokesman, said the leaders of the task force believed they had a strong sense of what is contained in the 15,000 documents that Assange is threatening to release shortly.

“We believe we probably know what’s in those,” he said. “And we believe, again, that they will pose some risk to our forces in Afghanistan and to others.”

Assange has offered few details about what is in the 15,000 documents, except to say that he held them back from release in July because they needed a detailed “harm minimization” review to avoid endangering individuals who might be identified in them.

Lapan said that Carr’s team turned its attention to the 15,000 documents over the last month as it continued to analyze the nearly 76,000 Afghan war logs that WikiLeaks released in late July in a collaboration with The New York Times, The Guardian newspaper of Britain, and the German magazine Der Spiegel.

“It was their task to go through that initial release of the 76,000 documents and determine what information in each of them might put either lives—or sources and methods, or operational security—at risk,” Lapan said of Carr’s operation.

The team’s assessments, he said, are passed to the United States Central Command, the military command that oversees American troops in Afghanistan, “so they can get it out to folks in the field to take whatever steps are necessary” to protect American troops and Afghan civilians whose identities are revealed by the logs.

Defense Department officials suggest that if there was ever any consideration of negotiating with Assange or participating in vetting classified documents before they were released on the site, that time has passed.

The Pentagon has demanded repeatedly that Assange post no additional leaked military documents and return whatever else he has—a demand that WikiLeaks has rebuffed. Officials say there is no aggressive Pentagon search for Assange, because he has been living openly in Europe for much of the summer and his newfound global celebrity means that he can be easily tracked.

The release of war logs in July outraged the Obama administration, which suggested that the information in the logs would leave WikiLeaks with “blood on its hands”—a phrase used by several administration officials.

Many Afghan informants were identified, by name and home village, in the documents posted in July, and Taliban leaders warned that they would use the logs to track down and kill the informants.

Lapan said that, so far, the Pentagon has no evidence to suggest that any Afghan civilians have been harmed by the Taliban as a result of the release of the 76,000 logs this summer—a bit of good news that, he suggested, might be attributed to the efforts of Carr’s team and Central Command to try to protect them.

Philip Shenon is an investigative reporter based in Washington D.C. He was a reporter at The New York Times from 1981 until 2008. He left the paper in May 2008, a few weeks after his first book, The Commission: The Uncensored History of the 9/11 Investigation , hit the bestsellers lists of both The New York Times and The Washington Post. He has reported from several war zones and was one of two reporters from the Times embedded with American ground troops during the invasion of Iraq in the 1991 Gulf War.