Robert Jeffress, Southern Baptist Convention leader and pastor of the 10,000-member First Baptist Church of Dallas, has never endorsed a political candidate, but at the Values Voters Summit on Friday, he announced that he was throwing his support behind Rick Perry. “I don’t think Michele Bachmann is going to win the nomination. I don’t believe that Herman Cain is going to win the nomination. I think it’s going to come down to a Perry-Romney fight,” he told me shortly before taking the stage to introduce Perry to the crowd. “And I felt like at this time, it was critical for a pastor to tell other Christians why it is imperative to vote for a Christian rather than a non-Christian.”

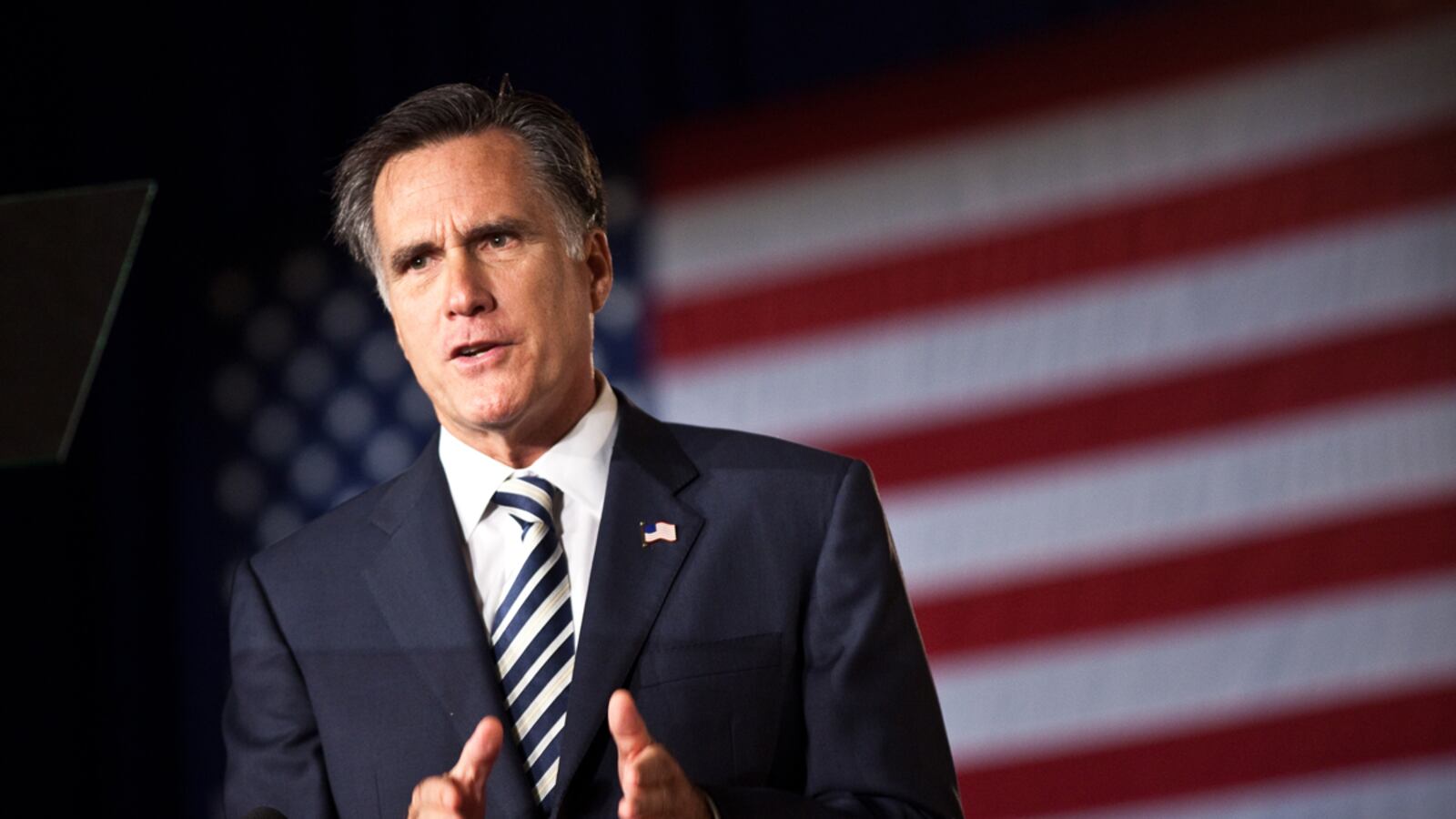

In other words, Jeffress, one of the first major religious right figures to choose sides in the GOP primary, wants to make sure that the Republican Party doesn’t nominate a Mormon. Romney’s religion, he says, “is going to play a huge role. It’s a role that many people are unwilling to speak about.” He, however, is more than willing. “Quite frankly, part of my hesitancy in supporting Governor Romney is I do not want to give credibility to a cult like Mormonism, which I believe having a Mormon president would do,” he says.

After Perry’s speech—a fairly underwhelming iteration of his standard stump address—Jeffress expressed similar sentiments to reporters gathered at Washington’s Omni Shoreham hotel for the religious right confab. Soon, the story of Perry’s anti-Mormon ally was all over the place. This creates a challenge for the Texas governor, but it also gives him an opportunity to capitalize on some evangelicals’ antipathy to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

By Friday afternoon, Perry was coming under pressure to distance himself from Jeffress. His campaign insisted he didn’t share Jeffress’s view, and that the organizers of the Values Voters Summit, not the Perry camp, had invited the preacher to introduce to the candidate. Nevertheless, Perry didn’t renounce Jeffress, which means he’s likely to continue fielding questions about Mormonism.

In the end, though, all this might work in Perry’s favor. After all, as Jeffress points out, he’s hardly alone in his views. The belief that Mormonism is a cult is the official position of the Southern Baptist Convention, the country’s largest Protestant denomination. In a June Pew Poll, 34 percent of white evangelicals said they’d be less likely to support a presidential candidate if he or she were Mormon. (Liberal Democrats were even more anti-Mormon, with 41 percent expressing reluctance to back an LDS candidate.)

It wasn’t hard to find people at the Values Voters Summit who either said they were uncomfortable with Romney’s faith, or claimed that people they know are uncomfortable with it, often a useful gauge of opinions that people hold but don’t like admitting to. “I can see where some people would be very uncomfortable about having a Mormon missionary knock on their door and say, ‘I want to show you what our president believes,’” says William Murray, chairman of the Religious Freedom Coalition, which promotes the rights of Christians in Islamic and communist countries.

William Estrada, director of Generation Joshua, which mobilizes young home-schooled evangelicals, says he has Mormon friends, and that he would consider supporting a Mormon with the right values. Still, he adds, “at the end of the day, I would strongly prefer to vote for a born-again Christian.” And his wife, he says, “wouldn’t vote for Romney because he’s a Mormon.”

Meanwhile, Estrada says that Jeffress’s decision to back Perry is significant. “I think that’s huge,” he says. “It’s a prominent evangelical Christian leader who is coming out and picking a side.” Indeed, among conservative Christians, Jeffress is an important figure. His television show, Pathway to Victory, reaches 1,200 stations. In January, he has a new book about the apocalypse coming out, jauntily titled Twilight’s Last Gleaming: How America’s Last Days Can Be Your Best Days. Mike Huckabee penned the foreward, writing of Jeffress, “I stand in awe of the clarity of his convictions and the clarion call for believers to come out of hiding and act like they serve a King!

Perry, then, can hardly afford to spurn Jeffress’s support. Given his lackluster performance in the Republican debates and conservative discomfort over his record on immigration, he needs help reinvigorating the base that once had such high hopes for him. Indeed, that’s partly why Jeffress decided to get involved. “There’s no doubt that Governor Perry stumbled in the debate. We all understand that,” he says. “And the truth is he will never become a cool, smooth, silver-tongued orator.” But what the country needs, says Jeffress, isn’t a skilled rhetorician, but “one who’s a conservative out of conviction, not out of convenience like Mitt Romney.”

Later on Friday night, Jeffress professed surprise that his comments about Mormonism had become such a big national story. “I’ve been shocked by it,” he says, pointing out that he said the exact same thing about Romney’s religion in 2007. A woman standing nearby interjected that all the uproar was simply because “the libs are afraid of Perry. They’re trying to run him down. They’re trying to attack him.” This impression, of course, can only help the Texas governor. Maybe Jeffress only contributed to it by accident. Or maybe he understands his audience.