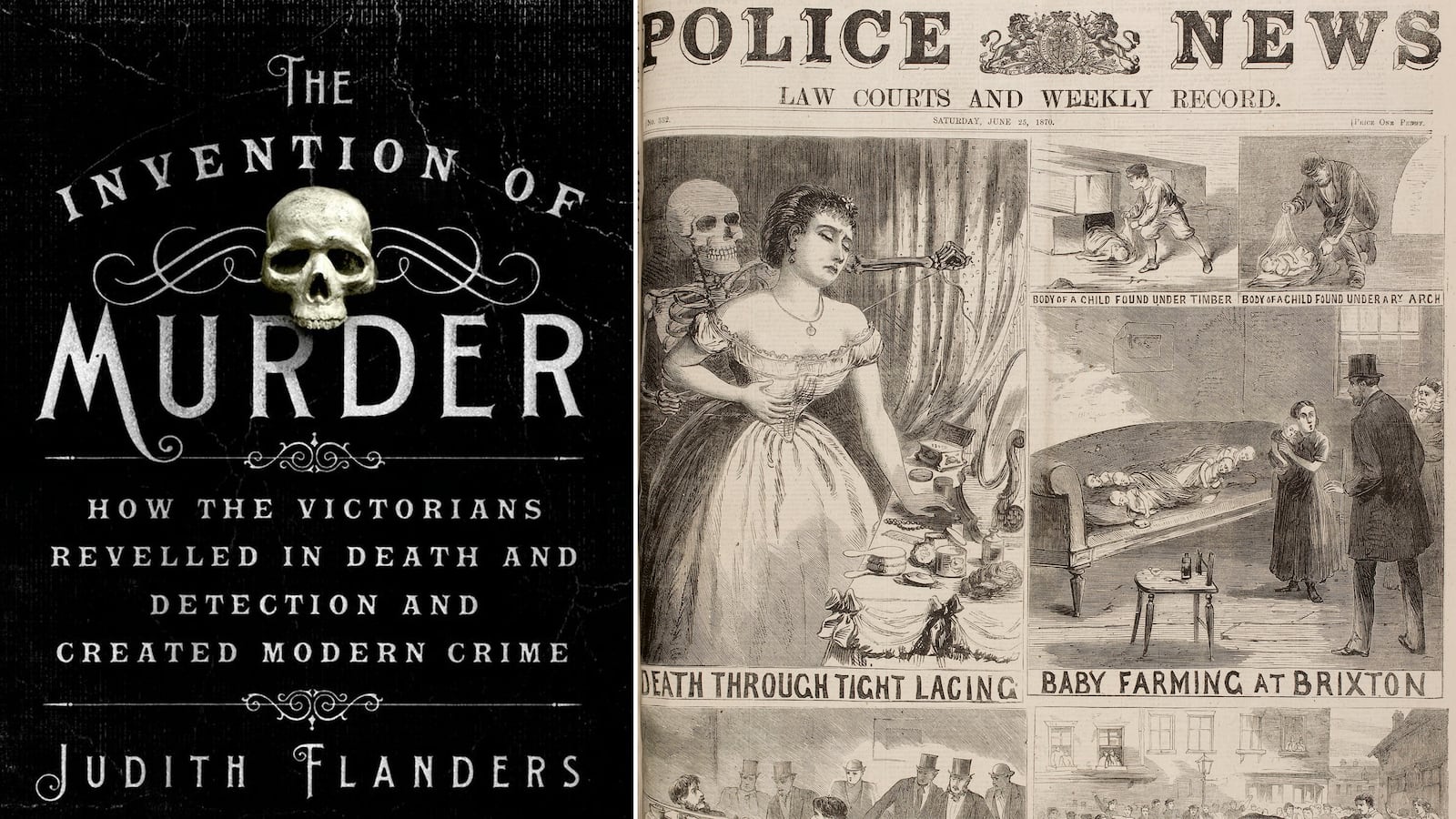

Victorian aficionado and British historian Judith Flanders begins her book on murder with some wise words from Thomas De Quincey: “Pleasant it is, no doubt, to drink tea with your sweetheart, but most disagreeable to find her bubbling in the tea-urn.” Even more enjoyable, though, he surmises, is to read about someone else’s sweetheart bubbling away. As Flanders demonstrates in her book, the Victorians loved to read about murder, and the newspapers took great pains to give the public what they wanted; even “prosperous, middle-class readers were avid for crime stories.” Indeed, murder so captured the public imagination that stories of dastardly crimes dominated popular entertainment in all its guises—from plays to poems and even the races, where greyhounds and horses were named after famous felons. Given the success of Flanders’s book in the U.K. and other recent histories like it (Kate Summerscale’s The Suspicions of Mr. Whicher, for example), it would also appear that the tastes of modern audiences are similarly inclined.

“I think what people like, in all kinds of nonfiction, including history,” Flanders explains when I meet her in London’s British Library, “is stories.” And The Invention of Murder certainly gives her reader plenty to choose from: a plethora of murder cases documented in all their gory details, from the well known, such as Burke and Hare the Edinburgh-based murderers who sold their victims’ corpses to the medical school for dissection, and the notorious Whitechapel murderer Jack the Ripper, through middle-class female poisoners, jealous husbands and wives, to wrongfully accused servants. Recalling the pathetic defense of one such unlucky teenager whose only argument was “My Lord, I didn’t do it,” sees Flanders’s eyes well up. “It’s heartbreaking,” she says.

It’s also precisely these tantalizing “little insights” that make Flanders’s work so accessible. “What I have been interested in all along is what I sometimes feel is missing from other kinds of history where you learn what, but you don’t learn what it felt like,” she explains to me. Flanders doesn’t get bogged down in attempting to prove a thesis-style argument—all you need to know about her books’ subjects are in their titles—and she’s well aware that some people criticize her for this absence, but she clearly doesn’t mind. “In a rather acid moment,” she laughs, “my publisher suggested that all my books should be called ‘Fun Stuff I’ve Found Out,’ and he’s not entirely wrong. It is kind of ‘Wow, look at this!’” He obviously doesn’t mind, either, as they all appear to great acclaim.

This is Flanders’s fourth book about the Victorian period (and she’s since written a fifth, The Victorian City: Everyday Life in Dickens’s London, already published in the U.K.). After a long career as an editor, she switched to the other side of the desk in 2001 with A Circle of Sisters, a biography of Alice Kipling, Georgiana Burne-Jones, Agnes Poynter, and Louisa Baldwin. Her longstanding interest in the period though is nothing more than “an accident,” really. The first book just happened to be set during the Victorian era, and “as I wrote it, I just became more and more interested in the social world in which these women lived.” Hence, her next book was the bestselling The Victorian House: Domestic Life From Childbirth to Deathbed (2003). Each of her works has grown organically out of its predecessor, she explains. Writing the chapter on theater in her third title, Consuming Passions: Leisure and Pleasure in Victorian Britain, “I realized so many of these plays were based on true crime, and I thought, how weird and wonderful. So that was the next book.”

The story The Invention of Murder tells about the Victorians’ obsession with crime is fascinating. Of course, in many ways the sensationalist element hasn’t changed; the plays of yesteryear are no different from the shows of the same subject that crowd today’s TV schedules. That said, “murder tourism” and “souvenir hunting” were much more socially acceptable pastimes than than they are today, and these weren’t just the activities of the uncouth working classes, for the “middle-class scavengers were every bit as avid.” Take the aftermath of Burke’s death, for example: even as his body was being taken down from the scaffold, “souvenir-hunters descended, grabbing at shavings from the coffin, or pieces of the rope.” The public dissection that followed was disrupted by a riot, as hordes of medical students tried to gain access, and when, after which, the remains were put on display for the general public, “perhaps as many as 30,000 came through the anatomy theatre.” That the courtrooms of accused female murderers were “filled with well-dressed women and girls armed with ... sherry, sandwiches and eye-glasses,” might seem unnecessarily and grotesquely vulturelike to modern readers, but musing on the subject, Flanders speculates that perhaps it’s just because “we’re much more bodily removed” today. “We’re not used to the physicality of bodies in the same way.”

Because the book is about how crime and murder was perceived by the rest of society, and not just a retelling of the various cases, Victorian novels—from Dickens, Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes, Wilkie Collins’s detective fiction, and Jack the Ripper–inspired fictional creations such as Jekyll and Hyde, Dracula, and Dorian Gray—were key source materials for her work. Bleak House, for example, uses the “trick ending, where all is revealed, soon a standard of detective literature,” for the first time: “now the reader becomes fascinated not by the crime but by its solution, by the detection of crime.”

“Realizing how every bit as much as the crime-fiction writers learnt from the police, the police learnt from the crime-fiction writers; that the development of the two was so tight and so interwoven that it’s impossible to separate them,” was, Flanders tells me, “just extraordinary.” A connection that’s made even more interesting when she informs me that her most recent work is actually a crime novel of her own (due to be published next year)—my first question is to ask whether it’s set in the Victorian era. “No,” she says with a laugh, it’s contemporary. But, she goes on to explain, since she’s always enjoyed reading crime fiction herself, what was particularly interesting while writing the murder book was working out exactly what was so attractive about the genre. “I decided that one of the things that had gone into that genre, with urbanization, with living amongst strangers, with the transitory nature of much of London particularly, was that the world became quite frightening. And what the traditional crime novel does is say, here are a bunch of strangers, but at the end only the one who has been identified as bad is removed from the group and taken away and punished. Everyone else by definition is good. It’s actually a very reassuring format.” A huge part of the entertainment factor of crime comes, she continues, from knowing that you are safe. Despite the blood-drenched pages, the actual crime rates in Victorian London were really quite low, lower than today—in 1810, for example, just 15 people were convicted for murder in the whole of England and Wales, which had a population of nearly 10 million. “You can afford to be sitting in Kensington, Bloomsbury, or Pimlico and be titillated by reports of Jack the Ripper precisely because you’re not an alcoholic prostitute in Whitechapel.” It’s the vicarious thrill. To return to De Quincey, murder “is very pleasant to think about in the abstract,” Flanders’ writes at the beginning of the book: “It is like hearing blustery rain on the windowpane when sitting indoors. It reinforces a sense of safety, even of pleasure, to know that murder is possible, just not here.”