TAIPEI—Taiwan will hold a presidential election this weekend that will have global and regional ramifications. The frontrunner, current Vice President Lai Ching-te, has vowed to protect Taiwan’s autonomy from Chinese aggression and strengthen ties with the United States. Beijing has intimidated Taiwan by buzzing its airspace with fighter jets and sending spy balloons and satellites over the island. But there’s another enemy vying to take Lai down, and it’s on TikTok.

The popular social platform, owned by Chinese company ByteDance, has been flooded with false or sensationalized videos by accounts exhibiting behavior consistent with organized Chinese disinformation operations, experts say. Most of the videos target Lai, who Beijing views as a supporter of Taiwan’s independence from Communist China, which claims sovereignty over Taiwan despite never having ruled it.

In one video by the account @ykcyedan, a masked woman angrily chides Lai for allegedly not paying his taxes. Others accuse Lai of conspiring to send young Taiwanese to war with China. In another, a young Taiwanese girl tells her audience how delighted she is to visit Harbin, a popular winter destination in northeast China, for the holidays. Scroll through enough of the videos and they begin to paint a picture of Lai as a warmongering tax cheat out to ruin children’s holiday dreams.

As Taiwan’s election fervor kicks into overdrive, the videos are racking up tens of thousands of views, raising concerns over whether the Chinese government can influence the app—and what voters see in the critical days before the election.

“The algorithm is deciding what you see. And that algorithm is ultimately controlled by the Chinese Communist Party,” said Tim Niven, lead researcher at Taipei-based Doublethink Lab, which tracks disinformation campaigns on social media.

As tensions between the U.S. and China have soared in recent months, Taiwan’s election has become a target for online disinformation campaigns. The winner will govern a country that’s a pivotal area of conflict between the two superpowers, playing a key role in their future relationship.

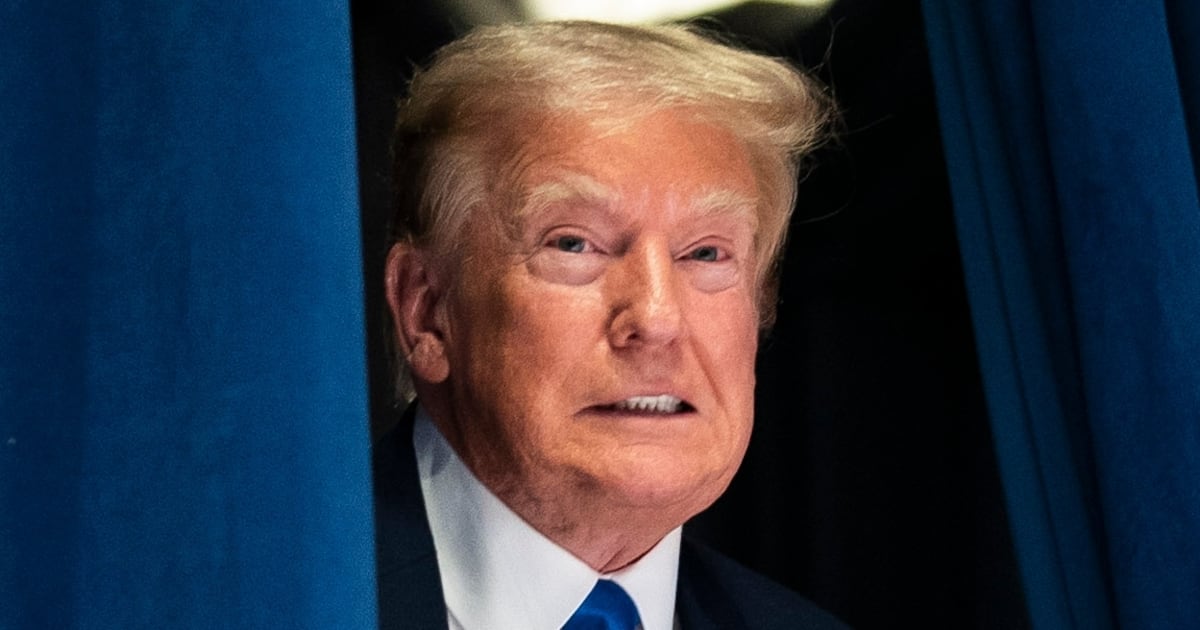

A victory by Lai, of the ruling Democratic Progressive Party, would represent a rebuke of China and the continuation of Taiwan’s informal alliance with the U.S., which supplies Taiwan with billions of dollars in military aid.

His two opponents see things differently. Hou You-yi of the opposing Kuomintang party wants deeper economic and political ties with China, which Lai said this week can only bring “fake peace.” A third party candidate, former Taipei mayor Ko Wen-je, has gained popularity among voters tired of Taiwan’s two-party politics.

Taipei is draped in the hallmarks of election season as the vote approaches. Candidates smile down from posters on buildings, buses, and trucks traversing the city streets blaring campaign slogans through megaphones.

But none of the three candidates—all men in their 60s and familiar political faces—have seized the excitement of the electorate, raising the possibility of an unexpected result driven by low turnout. And most Taiwanese feel there’s no real threat that China will imminently attack.

“I don’t think we are going to go to war with China,” said Lin Tsu-shin, an employment officer who plans to vote for Lai but is not excited by any of the candidates.

“They always bring up China issues,” she said. “They really need to focus more on how to make Taiwan a better place.”

Taiwan joined the U.S. and other countries in barring TikTok from government devices in 2022, due to concerns over data security. Lai and his fellow party members do not have TikTok accounts.

But at least one quarter—likely more—of Taiwan’s 24 million citizens use TikTok. Ko, the third-party candidate, has reached young voters by posting quirky videos on a near-daily basis to the platform.

TikTok’s popularity among young people has also given Chinese online trolls a rare, unchecked portal into reaching Taiwan’s normally China-skeptical population. Sock puppet accounts are specializing in rapid-fire edits showing Taiwanese influencers and political pundits criticizing Lai, according to Niven, but amplifying their most extreme claims and taking them out of context before feeding them into the algorithm.

“We’ve seen a lot of cutting up and reusing local content, what I would describe as putting Taiwanese polarization on steroids,” Niven said.

This strategy “limits the diplomatic risk for [China],” he added, as it appears “they’re not creating the disinformation,” but instead sharing videos showing what Taiwanese people already think.

For instance, one video from the @ykcyedan account shows Hou’s running mate, Jaw Shaw-kong, referencing a recent advert showing outgoing President Tsai Ing-wen driving a car with Lai and his vice presidential candidate. “On what road?” Jaw asks. “The road to war!” A text overlay says Lai will “take Taiwan to war, corruption and danger.”

The account is one of several posting in patterns indicative of an organized disinformation operation, Niven said, receiving likes and comments from accounts using profile photos ripped from Chinese shopping sites and generative AI companies. Some of the videos mistranslate terminology commonly used in Taiwan from that used in China.

“We’re making guesses, but based on our judgment, these patterns are far more consistent with the CCP than they are with other known threat actors,” Niven said.

Determining the actual source of disinformation can be difficult. In December, the research firm Graphika published a report documenting a widespread influence operation publishing coordinated videos attacking Lai on TikTok and YouTube, claiming the DPP is responsible for domestic political scandals such as an egg shortage and the alleged poisoning of kindergarten students. The videos were then spread by a network of more than 800 Facebook accounts.

Graphika could not determine who was behind the operations, but it observed multiple inaccuracies in the campaign’s use of Taiwanese despite making “a real effort to appear ‘local,’” Graphika analyst Libby Lange said.

After Graphika released its report, YouTube removed the Agitate Taiwan account for violating its rules against spam, deceptive practices and scams. TikTok did not, and at least 380 videos remain available, some of which have received tens of thousands of views. A TikTok spokesperson told NPR last month it had not found evidence the account was inauthentic.

TikTok also makes it difficult for researchers to analyze the source of information, Niven said, due to its reluctance to grant API access and release internal information, such as Meta’s quarterly threat reports.

Last month, TikTok announced a collaboration with Taiwanese fact-checking organization MyGoPen to correct disinformation on the platform. Election-related videos now contain information links directing users to an in-app “2024 Election Guide” that points users to official resources, such as the website of Taiwan’s Central Election Commission.

But these alerts don’t reach all election-related content. For instance, the disclaimer does not appear on the latest videos posted by the @agitate_tw TikTok account.

Inauthentic actors have progressed from posting false information—which is easy to correct—to “more conspiracy theory type of disinformation” that is harder to disprove, MyGoPen project manager Robin Lee said. Online trolls who used to post pro-China propaganda have grown into more nuanced narratives, such as saying that Lai and the DPP will lead Taiwan into war.

“Now, it’s different. They just want you to be anti-U.S., anti-Japan, anti- any country friendly to Taiwan,” Lee said. “They try to create chaos.”