In political campaigns, we are always fighting the last war.

Donald Trump’s election in 2016 was, in no insignificant part, a reaction to the disastrous 2003 invasion of Iraq and the subsequent years of quagmire.

As an upstart GOP primary candidate, Trump said George W. Bush’s war of choice was the “worst single mistake ever made in the history of our country.” Trump took advantage of GOP voter disillusionment, then weaponized his distance from the Republican establishment to make the case for America to retreat from its global leadership role, and only consider “America First.” It was this message that helped Trump handily dispatch the “mainstream” GOP’s original consensus choice: Bush’s own brother Jeb.

That was in 2016. But that is no longer the world we live in.

Following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, there’s no going back to “America First” as it was. That’s not to say the public is clamoring for a war with Russia. But the Trumpian worldview that embraced Vladimir Putin and threatened to abandon NATO has, for now, been repudiated. Republicans with their ears closest to the ground already know this.

J.D. Vance, a Republican candidate for the U.S. Senate in Ohio, last month tried to channel Trump’s nativist populism, saying that he didn’t want U.S. troops to fight and die over Putin’s invasion of Ukraine. “I gotta be honest with you, I don’t really care what happens to Ukraine,” Vance said, to make the point perfectly clear.

But following a recent Vance campaign event, attendees told NBC News that “images of death and destruction on TV” had helped form their opinions about whether or not the U.S. should support a besieged Ukraine. “Many were also unequivocally supportive of sanctions and the oil ban, expressing a need for empathy and generosity,” NBC News reported.

To paraphrase Mike Tyson, every “America First” isolationist has a plan—until they watch some kid get hit in the mouth on TV.

Ohio’s primary is May 3, just weeks away. While it’s true that his campaign was already struggling, Vance has somewhat backtracked on his comments, a clear confirmation that he was not reading the room.

Vance isn’t alone. In North Carolina, Trump-backed candidate Rep. Ted Budd is on defense after praising Putin. “As Ukrainians bled and died,” former GOP Gov. Pat McCrory said in a video bashing his primary opponent, “Congressman Budd excused their killer.”

Budd is now trying to dig himself out of this mess by explaining that Putin is “intelligent” but “evil.” This clarification reflects a changing political reality on the right, as it pertains to Putin. As National Journal’s Josh Kraushaar colorfully put it, “Putin is less popular than syphilis.”

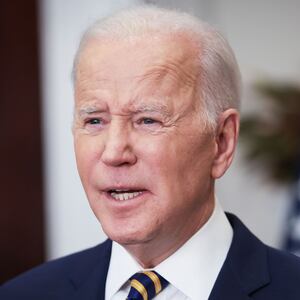

This feedback is not merely anecdotal. According to a Quinnipiac poll released last week, a majority of Americans—including 74 percent of Republicans—think Joe Biden “has not been tough enough” when it comes to punishing Russia for the invasion. Meanwhile, 64 percent of Americans—including 61 percent of Republicans—hold a favorable view of Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky.

Of course, public opinion matters most to people facing competitive races on upcoming ballots. The most loathsome Republicans—Reps. Marjorie Taylor Greene and Paul Gosar (who spoke at the white nationalist America First Political Action Conference, where the audience cheered Putin) and Madison Cawthorn (who called Zelensky a “thug”)—are ensconced in safe districts, and their national infamy hasn’t hurt them at the local level to date.

But make no mistake, the events of the last few weeks have brought implications that transcend even American politics.

“The invasion has already done huge damage to populists all over the world, who prior to the attack uniformly expressed sympathy for Putin,” wrote Francis Fukuyama. “That includes Matteo Salvini, Jair Bolsonaro, Éric Zemmour, Marine Le Pen, Viktor Orbán, and of course Donald Trump.”

Trump can never be counted out. But losing reelection, inciting a riot, and then finding himself on the wrong side of an emerging foreign policy shift hardly feels like the makings of a brilliant political comeback.

A field of anti-Trump Republicans is already lining up to run against him in 2024, according to the Associated Press. Should most of Trump’s endorsed 2022 candidates lose—a possibility even before Russia crossed Ukraine’s border—it would only chum the waters more.

Would-be primary opponents might rationalize that although Trump remains personally popular in the GOP, the greater electorate is ready to move on from the unnecessary international drama that Trump caused on an almost daily basis as president.

This is not an absurd theory. The world is dynamic. Trump could still win in 2024, but the isolationist populism he deployed in 2016 isn’t as likely to land today.

Of course, the fickle court of public opinion could swing back Trump’s way between now and 2024. Perhaps MAGA will finally settle on a consistent message (is Biden too tough or too weak on Russia?), and the horrors of the war in Ukraine will end, with Putin’s troops leaving a country they had no business attacking in the first place.

Regardless, one thing is certain: Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is one of the biggest international crises and upending of the world order in decades. This means that Trump can’t run again in 2024 by playing his greatest hits. He won’t get much mileage out of attacking George W. Bush and the GOP establishment’s “forever wars.” And praise for Putin—and suggesting that he can be managed or (even more ridiculous) turned into an ally—simply won’t resonate.

That was the last war.