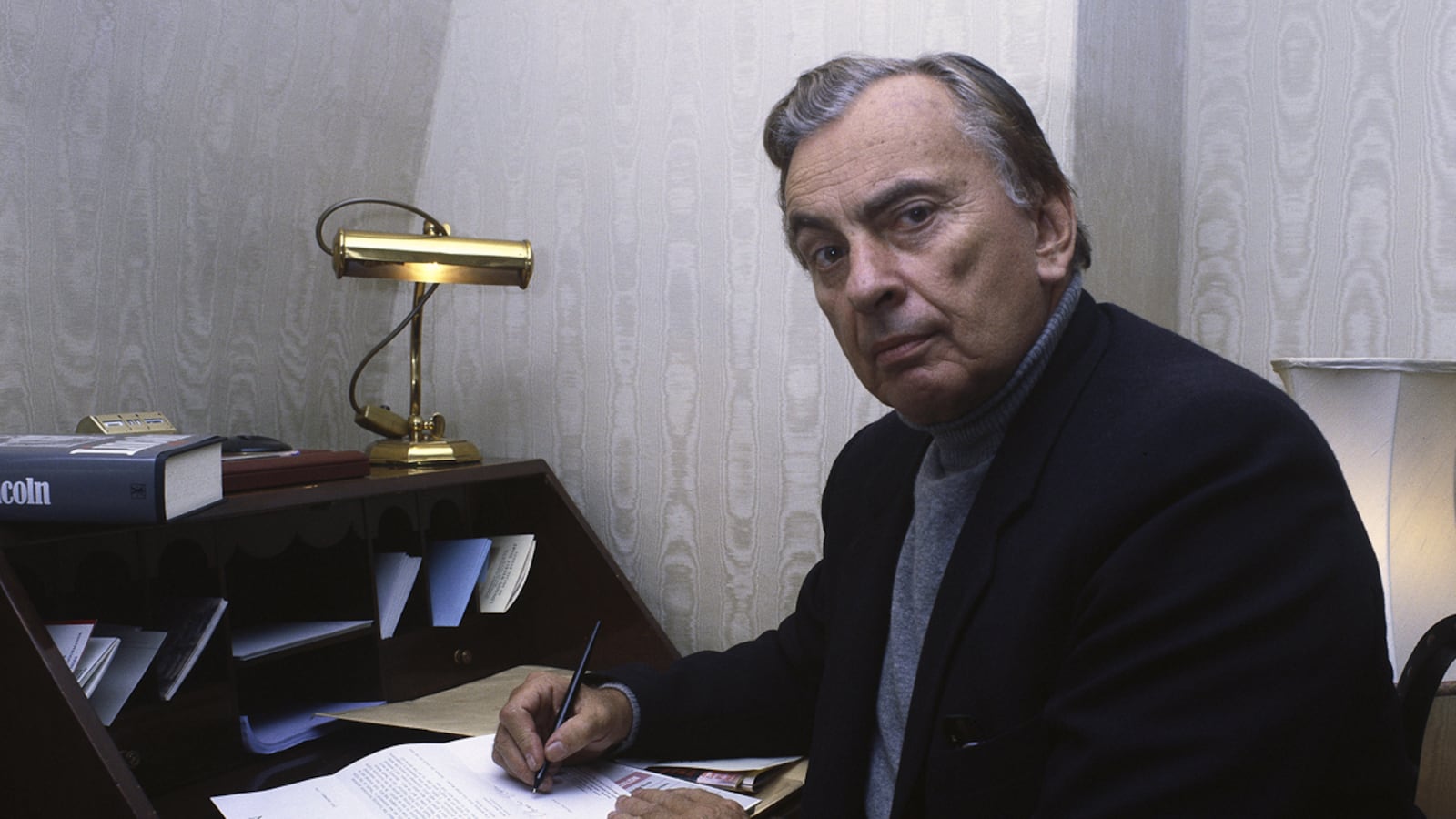

In 1982, when Gore Vidal was running in the California primary for the Democratic nomination for the U.S. Senate, he was backed by Max Palevsky, a former UCLA professor of symbolic logic and mathematics, who became a multimillionaire computer mogul, and then wealthier still after he invested some of his first fortune in a Silicon Valley startup called Intel.

But Palevsky's real passion wasn’t digital, it was political. And he wielded a goodly chunk of his fortune in support of liberal causes and candidates that included Robert Kennedy, George McGovern, and Tom Bradley.

So, when Vidal entered the California senate race two years into the reign of Reagan, for Palevsky, his considerable intellect notwithstanding, choosing Gore was a no-brainer. The opposition in this primary would be formidable--the sitting Democratic governor, Jerry Brown, coming to the end of his second term, and looking now to go national.

But, while Brown may have been "Governor Moonbeam" to the Republicans, he wasn't nearly left enough for Palevsky. Not when the laser-tongued and arsenic-inked paladin of letters, Gore Vidal, was stepping forward with both pen and sword.

What the big money in politics is mainly needed for, however, is to cover the immense expense of media. And what fills the blank pages, billboards, airwaves, and screens that media is, is advertising.

A friend of mine was friends with Max, and she recommended me to create the ad campaign for Vidal's run.

I was young, but having started my career in the mailroom of a major international ad agency at age 19, had considerable experience. Unusually wide as well—for airlines, high tech, oil companies, wine and booze, cars and motorcycles. I'd also done scores of movie campaigns like Jaws and All the President’s Men. And, relevantly, two winning campaigns for California initiatives.

What my friend apparently did not know, I was then as I am now, a conservative. Or, more accurately, as I've long described myself, a Tory anarchist. There is no party in America for that bent, so I've always been a registered Republican.

Understand that being not only an admitted conservative, but an often vocal and declarative one, in an ad agency creative department, is about as common and welcome as it would be in a Screen Actors Guild meeting.

The prospect of having Gore Vidal as a client couldn't have been more delicious. Not just for the irony, but because I'd always gotten a kick out of Vidal as a public personality. Always enjoyed his judiciously meted acid attacks on talk shows and political debates.

Hell, my own mother, who loved seeing the mighty brought low, was Vidal’s biggest fan. I couldn't imagine anything more fun than to work on his campaign.

Besides, in advertising as in criminal law, every client is entitled to a stout defense. Or offense, as in this case. I was more than happy to give it my best.

I was offered the job, accepted, and soon found myself driving to my first meeting with Vidal at his home high in the Hollywood Hills. It was all very informal. I met his longtime companion Howard Austen, an unprepossessing man who padded in and out, very quiet, with no obvious interest in the campaign.

I remember being surprised, given what I had interpreted (wrongly) as his mid-Atlantic demeanor, at the dark and heavy Italian, I guess, furniture. And the vermillion wall covering in the library that seemed very 19th-century bordello.

We sat down, talked casually about direction and strategy. This wasn't going to be over-think. I'd been brought in late in the game and now I had to get spots, which he would deliver, written and produced for him to put on air very soon.

Vidal, was, as I'd hoped, a kick, although quite serious and earnest about the race. And not the least haughty or intimidating or acerbic, but helpful, constructive, and conscientious.

And though we were nominally running against Jerry Brown, he wanted really to be running against Ronald Reagan. Or, more precisely, he wanted not a partisan run against Reagan or the Republicans. Way beyond that, Gore Vidal was running against the way America was turning out.

By his lights, not very damn well.

I'm sure he didn't intend or expect to win, of course. He just wanted a bullier pulpit than a talk show from which to sound the alarm.

And, as for me personally, in one regard, I was particularly delighted with him, and pleased for myself, that Gore Vidal delivered the copy I wrote for his spots without changing a word.

Though he had written novels, movies, plays, and essays, all with great success, he deferred to me in the peculiar haiku called the 30- and 60-second spot.

For all his reputation for hauteur, I would forever after remember this evidence of Vidal's graciousness and self-confidence. The public display of arrogance, was in some essential sense, an act.