Yusuf Mingazov met his father Ravil—a former Russian ballet dancer—for the first time through a video call between a Red Cross office in Britain and the Guantánamo Bay detention camp in Cuba, where he had been imprisoned for more than 14 years.

“It was kind of difficult to explain the emotions and everything, but it was nice to see him because it was the first time,” said Yusuf, 22, who was born in Russia.

He was just three years old when his father was arrested in Pakistan in 2002 and accused of being associated with al Qaeda and the Taliban. The U.S. concluded that he was a “low level fighter”—which he denies—before clearing him for release in 2017, but he was not granted freedom. Instead, Ravil Mingazov was sent to the United Arab Emirates, where he languishes in another jail cell, in arguably even worse conditions.

Now, he faces the threat of being forcibly sent back to Russia, where his family fears he could be detained, tortured, or killed.

Mingazov’s family maintains that fleeing persecution in Russia was the reason he was in Pakistan and Afghanistan in the first place. “He wanted to raise me in an Islamic country because he wanted the best for me and to live in peace,” Yusuf said.

As a child, Yusuf traced an image of his father through photographs and stories about his life as a soldier and a Red Army ballet dancer in the 1980s and ’90s, told by friends and family in his homeland of Tatarstan, in eastern Russia.

Yusuf now lives with his mother and siblings in London, where they were granted political asylum. He has built a relationship with his father through a series of intermittent phone calls from Guantánamo and during his father’s resettlement in the UAE, where rather than being reintegrated into normal life, he has been imprisoned. The scheduled one-hour video exchanges between father and son in the U.S. prison soon became sporadic five-minute calls at random hours.

“Even in Guantánamo, at least I could see a smile on his face,” Yusuf said. In the UAE, he said his father, who is 57, sounded “broken,” and the line would be cut when he complained of the prison conditions and solitary confinement. Soon the calls stopped.

“He liked Guantánamo more than the UAE,” Yusuf said.

Earlier this month, UN human-rights experts raised an alarm about the possibility of Mingazov, a Muslim of Tatar ethnicity, being forcibly repatriated to Russia.

“We are seriously concerned that instead of releasing him in accordance with the alleged resettlement agreement between the U.S. and the UAE, Mr. Mingazov has been subjected to continuous arbitrary detention at an undisclosed location in the UAE, which amounts to enforced disappearance,” the experts said.

“Now he risks being forcibly repatriated to Russia despite the reported risk of torture and arbitrary detention based on his religious beliefs.”

The statement follows similar concerns about 18 Yemenis who were feared to be on the verge of forced repatriation last year. Four Afghans were already forcibly sent back home with one of them dying “due to illness resulting from years of torture, mistreatment and medical neglect at both Guantanamo and in the UAE,” according to an earlier statement by the experts.

“It is not acceptable that detainees who did not return home, after years of arbitrary detention at Guantánamo Bay, from fear of persecution are now being repatriated with no judicial oversight or possibility to challenge this decision,” the experts added.

The Last Days in Guantánamo Bay

Mingazov was one of three former Guantánamo detainees who were cleared for release and put on the last plane out two days before former President Donald Trump was sworn into office on Jan. 20, 2017. During Trump’s election campaign, he vowed to keep the prison open and “load it up with bad dudes.” Once he was in the White House, he signed an executive order to keep the prison open, reversing President Barack Obama’s order to close it.

When in Guantánamo, Mingazov told his U.S.-based lawyer, Gary Thompson, that he felt unsafe returning to Russia, where seven former Guantánamo detainees were imprisoned and tortured when they were forcibly sent back in 2004. Mingazov was resettled with 22 other former detainees in the UAE instead. All the men came from countries shaken by conflict, where the risk of violence and persecution is reportedly high.

UN experts looking into Mingazov’s case were informed of possible plans to repatriate him through Thompson, his lawyer, and the British-based human-rights legal organization Reprieve; both remain in regular contact with Mingazov’s family in Britain and Russia. His family had informed Thompson and Reprieve that Mingazov’s mother, in Russia, had been visited by government authorities in late June to verify his identity for a passport, as had been the case with the Afghans who were forcibly repatriated to their country.

“It followed a pattern we had seen, and it was deeply concerning,” said Katie Taylor, the deputy director of Reprieve and coordinator for the Life After Guantánamo project at the organization, which was established more than a decade ago with money from the UN Voluntary Fund for Victims of Torture.

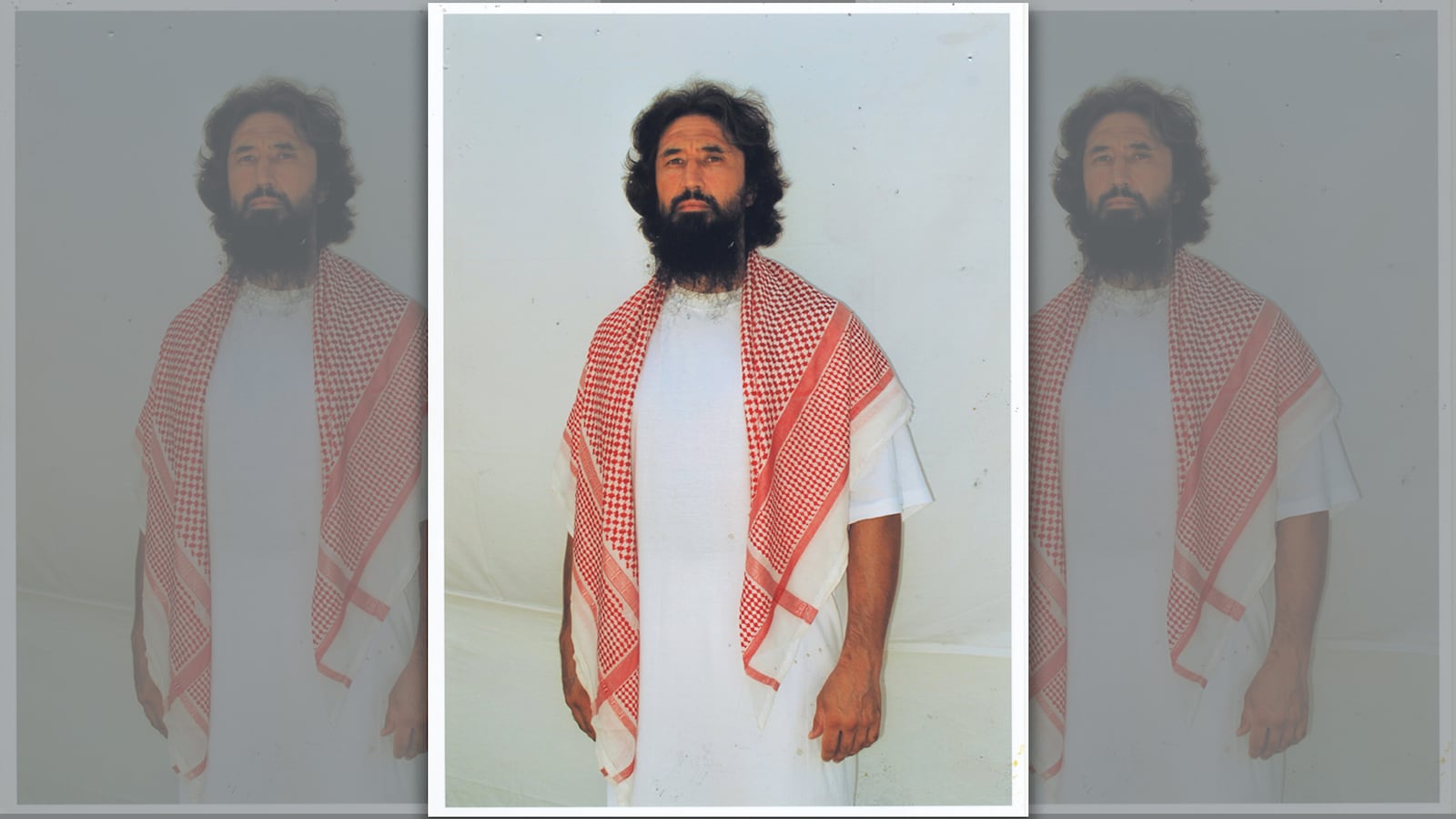

Ravil Mingazov was in the Russian army before quitting the country.

Daily Beast/Photo HandoutImprisoned Without Charge, Resettled Without Rights

As the Biden administration renews efforts to close the prison that Obama unsuccessfully attempted to shut down, advocates for current and former Guantánamo detainees are arguing that more needs to be done to ensure their rights are protected after their release, particularly those who need to be resettled in third countries.

Currently, 39 prisoners remain in the detention camp at an estimated cost of $13 million per inmate each year, according to one report. Eleven have been approved for release, with five of them from conflict-affected countries such as Yemen. They may have to be resettled in third countries. Since 2002, around 780 detainees have been held as prisoners of war, according to The Guantànamo Docket, a database on detainees compiled by The New York Times. Among them were 140 detainees who were approved for release and resettled in 30 host countries because it was too unsafe for them to return to their own.

According to data collated by Reprieve, detainees resettled in 19 of those now 29 host countries have precarious legal status, ranging from temporary renewable residency to completely lacking documents. The organization said it would not disclose the status of particular detainees in particular countries to protect its clients.

But Taylor at Reprieve said that a lack of secure legal status remains a big problem facing resettled detainees. “It’s really difficult for people to rebuild their lives and take steps to successfully reintegrate back into society if they feel they can be chucked out at any given moment,” she said.

The UAE and Senegal are among the countries that accepted detainees but then sent them back to their original countries, against their will, to conflict zones in recent years. In 2018, Senegal forcibly repatriated two Libyans to their war-shattered country after a two-year stay in Senegal. Former members of the Office of the Special Envoy for Guantánamo Closure, set up by President Obama to oversee resettlements and repatriations of detainees and the closing of the prison, have said that these transfers to third countries were made with humanitarian assurances and an understanding that the men would be helped with rebuilding their lives and reintegrating into society. But that oversight stopped under the Trump administration, which immediately closed the office.

In a 2013 communiqué over a UN special rapporteur’s letter to the office regarding concerns about the repatriation of an Algerian detainee, the U.S. mission to the UN in Geneva said, “The U.S. Government seeks assurances of human treatment, including treatment in accordance with the international obligations of the destination country, in particular under the Convention Against Torture.” However, families of both the Yemeni detainees and Mingazov have complained of reports of abuse and prolonged periods of solitary confinement in prison in their resettled countries.

All agreements between the U.S. and countries where former detainees have been resettled are confidential. Yet a recent statement raises questions about how the U.S. sees its legal and diplomatic responsibility after resettlement. A letter written by Daniel A. Kronenfeld, a human-rights counselor who still works at the U.S. mission in Geneva, responded to the special rapporteurs’ concerns that Yemeni detainees in the UAE would be forcibly repatriated. In it, he asserts the individuals were transferred “in a manner consistent with the United States’ legal obligations and following agreed-upon assurances between the United States and the UAE regarding the terms of their resettlement in the UAE.”

He adds: “Following the transfer of detainees out of Guantánamo, former detainees are no longer in the control or custody of the United States. Host countries are in the best position to provide information on the current situation of Guantánamo transferees.” The response was dated Jan. 15, 2021—five days before Biden was sworn in.

PassBlue, an independent public-service journalism organization that covers the UN, contacted the U.S. ambassador to the UN, Linda Thomas-Greenfield, and Lana Nusseibeh, the UN ambassador for the UAE, for comment about the statement by the special rapporteurs on Mingazov’s case, but received no response by deadline. The press office of the Russian ambassador to the UN, Vassily Nebenzia, did not respond to questions sent via email asking whether Russia was planning on having Mingazov repatriated and whether he would be safe from persecution if he were returned home.

In June, the UAE won an elected seat in the UN Security Council for the 2022-23 term, and two years ago, the country reportedly paid $400,000 for a four-month contract with a Washington public-relations firm to help manage the UAE’s international image, given its major role in the Saudi-led coalition bombing of Yemen. The PR account was headed by an ex-staffer of Samantha Power, the former U.S. ambassador to the UN under the Obama-Biden administration. (Power now leads the U.S. Agency for International Development, or USAID.) The special rapporteurs have also expressed concern about the UAE’s jailing and alleged disappearing of prominent activists and the use of counterterrorism laws to justify its actions.

In January 2017, Thompson, who represented Mingazov for more than a decade and was with him through his hearings with the U.S. Periodic Review Board, an interagency entity that determines whether a detainee can be safely released, was uncertain as to whether his client would be freed. His being Russian made him a “political hot potato” at the time, Thompson said. Latvia had been floated as an option for resettlement, but Mingazov feared it was too close to his homeland.

When the UAE came up as an option, Mingazov expressed excitement about being settled in an Arab country, and it was understood that he and other detainees would take part in a rehabilitation program that would last a maximum of one year, according to Thompson and Reprieve.

“It felt like such a tremendous victory at the time. I remembered calculating the flight time on the plane, and I wanted the wheels to touch down in the UAE before Trump’s inauguration,” Thompson said, adding that he feared Trump “would order the plane to turn around midair.”

Thompson and Reprieve have said that they have no confirmation of where Mingazov is being held in the UAE and that his family has been given limited access to him over the years, with his mother having seen him once on a trip to the country in 2018 at a prison named Al-Razeen, located in the desert outside Abu Dhabi. Some human-rights groups have called the prison “the Guantánamo of the UAE” because of its alleged use of torture, loud music, and prolonged solitary confinement, for which the U.S. base became notorious.

A ruling earlier this year by the European Court of Human Rights stating that Russia tortured and forced confessions from men accused of terrorism has also raised concern among human-rights groups working on issues related to Guantánamo detainees. At the summit meeting with Biden and President Vladimir Putin in Geneva last month, Putin publicly criticized Biden for U.S.’ black-site CIA interrogations and the continuing existence of Guantánamo.

“The Biden administration needs to hold the UAE government accountable,” said Thompson. “Whatever diplomatic assurances the UAE gave have all turned out to be lies… The UAE took these men and made promises to the U.S. government, our government, as to how they will be treated and they have ended up putting these men through something worse than Guantánamo.”

Insiders connected to past and present detainee cases have said that Biden has assembled a small team of people looking into issues surrounding the closing of Guantánamo and that there is hope there might be discussions about how to deal with unsuccessful resettlements. The Biden administration just released a Moroccan detainee to his homeland, bringing the total population of Guantánamo down to 39 men, with 10 recommended for transfer to their homeland or to third countries with security arrangements.

U.S. Accountability For Guantánamo

The recent statements from the UN special rapporteurs have been part of a longstanding campaign to pressure the U.S. to shut the prison and hold key figures accountable for alleged torture and illegal detention of detainees in both Guantánamo and former black sites around the world. Special rapporteurs on torture and counterterrorism over the years have tried to access the camp but were refused visits because of restrictions set by the U.S. government that would prohibit the UN experts from meeting with and having private discussions with detainees, according to two former special rapporteurs on torture.

The human-rights specialists have also called for the defense counsels of detainees accused of involvement in the Sept. 11 attacks to gain access to classified records of their interrogations and other evidence used to charge and prosecute them, so that they can receive due process. Additionally, they called for access to medical records for detainees who have been allegedly tortured, including Ammar al-Baluchi, the nephew of Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, accused of transferring money to the Sept. 11 hijackers. Moreover, the experts have criticized the use of testimony that has been obtained through torture in the continuing military commissions for the few Guantánamo detainees who have been officially charged with crimes.

Manfred Nowak, a human-rights expert and former special rapporteur on torture, led a 2010 report into “secret detention in the context of countering terrorism” that was released four years before the Senate report in 2014. He interviewed former Guantánamo detainees as well as many people who had been detained in black sites. Ni Aolain, the special rapporteur on the promotion and protection of human rights while countering terrorism, said she was releasing a follow-up report in March 2022.

“The resettlements have failed to address the fundamental issue of accountability for the acts which cause the need for resettlement in the first place—which was rendition, systematic torture, and arbitrary detention, in violation of international law,” said Ni Aolain.

Nowak said that Biden has a “major chance” to hold those responsible for the torture outlined in the Senate Intelligence report and for the arbitrary detention in Guantánamo. “The Biden administration has the same obligation to really look into the past and bring the perpetrators of these forms of torture to justice and to pay reparations.”

Six years ago, in 2015, Thompson and Mingazov’s family tried to have him released to Britain. In a letter attached to a formal request written to the country’s Home Office, just short of a year before he was approved for release by the U.S., a teenage Yusuf writes about having seen his father only through a “very old family video” — and he asks the office to “please give him back to me.”

Years later, the uncertainty plagues him every day. “We’ve been worried about them sending him to Russia. If they send him to Russia, we know he will die,” he said during a recent phone call. But Yusuf still hopes he will one day meet his father face to face.

Reporting for this story was supported by a fellowship from the Ira A. Lipman Center for Journalism and Civil and Human Rights at the Columbia Graduate School of Journalism.