The New York Police Department, working mostly in secret with private companies and in-house data scientists, has developed its own crime-forecasting technology. A new tranche of previously unseen documents, provided exclusively to the Daily Beast, offer the deepest look to date at the NYPD's efforts at so-called predictive policing—a technique that independent researchers and academics have excoriated for “tech-washing” racially biased policing methods by using algorithmic analysis of flawed data to offer a veneer of objectivity to justify objectionable law enforcement tactics.

The efforts began in 2014, under former Police Commissioner Bill Bratton, who has labeled crime forecasting “the wave of the future,” and who had initiated one of the earliest and most advanced predictive policing programs during his term leading the Los Angeles Police Department.

Two private firms participating in a 2016 predictive policing pilot with the NYPD sought to use non-law enforcement socioeconomic data such as welfare records, renter and homeowner data, and census records that have questionable utility in predicting crime. The department did not continue its relationship with the private-sector prediction companies over concerns about accuracy and forecasting methodology used by the firms and instead built out its own in-house prediction algorithms .

Despite the NYPD's success in reducing New York City's crime rate to levels not seen since the 1950s, the department has come under fire for heavy-handed and racially biased policing practices such as the stopping, questioning, and frisking hundreds of thousands of overwhelmingly black and Latino men every year during the term of Police Commissioner Ray Kelly. Other troubling techniques have emerged recently, such as the forced swabbing of hundreds of black Queens residents in the search for Katrina Vetrano's killer.

Skeptics of crime forecasting fear that predictive policing will provide justification for these discriminatory practices and further ingrain them in the NYPD's culture.

“The concern here, and with all systems that rely primarily on police department data for predicting crime, is that the underlying crime reports that they're using may not reflect the prevalence of crime in an area, but more the policing practices and policies of a certain precinct,” said Rashida Richardson, the director of policy research at AI Now, a public policy think tank that focuses on emerging technologies and artificial intelligence. Richardson recently co-authored a law review paper on predictive policing system that highlighted the use of “dirty data”—information obtained in an unlawful way, such as the millions of unconstitutional stop-and-frisk encounters conducted by the NYPD—in crime-forecasting systems.

After reviewing the NYPD's predictions at the request of The Daily Beast, Richardson observed that the NYPD system did not differ significantly from the models she researched. “These predictions are going to predict where officers typically target individuals,” she said.

Kristian Lum, the lead statistician at the Human Rights Data Analysis Group who has also studied crime forecasting, said that NYPD's retention and use of historical crime data, regardless of whether it was gathered unconstitutionally, poses a major concern. “We really have to worry about stop-and-frisk data,” said Lum.

The data used in the NYPD's predictions, she said, does not take into account if an incident resulted in an arrest, a criminal charge, or a conviction, calling into question the accuracy of such predictions. “To be able to do close to real-time forecasting, you can't wait for reports to be confirmed or for arrests to be adjudicated. You have to take the arrests in their messy, raw form.”

Along with the scope and details of its crime forecasting work, the department has also sought to conceal how it uses powerful cellphone interception technology, a hefty data-mining contract with the defense contractor Palantir that was leaked to the press, and the “smart video” analytics it has incorporated into a citywide network of video cameras, sensors, license plate readers and criminal incident data known as the Domain Awareness System.

The information about NYPD's predictive policing program provided to The Daily Beast was pried loose in 2018 by the Brennan Center for Justice, a New York-based policy institute, following two years of litigation under the state Freedom of Information Law. The files offer the first in-depth look at NYPD's crime forecasting efforts, which have only been hinted at in passing by department officials in white papers and public statements.

A related tranche of documentation made public in 2018 uncovered the involvement of three predictive policing firms – PredPol, Azavea, and KeyStats – in an NYPD predictive policing trial.

For years, the NYPD has been interested in developing predictive capabilities for its vast array of surveillance equipment. As part of the Domain Awareness System, NYPD developed pattern-recognition algorithms capable of recognizing unattended packages in sensitive areas, or forecasting the potential travel patterns of watch-listed cars tracked by license plate readers.

The documents, along with a 2017 academic paper written by senior NYPD analytics personnel, make clear that NYPD's rollout of predictive policing algorithms began in 2013. At that juncture, the police department was expanding the Domain Awareness System from headquarters to every precinct. “As part of this expansion, we developed and deployed predictive policing algorithms to aid in resource-allocation decisions,” according to the academic paper.

According to the department's account, it had created separate algorithms to predict seven crime categories: shootings, burglaries, felony assaults, grand larcenies, grand larcenies of motor vehicles, and robberies. The paper does not make any mention of what inputs the NYPD uses for its in-house crime-forecasting tools.

Attorneys from the Brennan Center, who analyzed the predictive policing data, say that the heavy redactions in the papers they were provided, lack of information about the source datasets used by the algorithm, and the absence of explanation about how the predictions are used by precinct commanders all raise concerns. By design, NYPD's system does not save the predictions it generates, nor keep an audit log of who creates or accesses them. The outputs provided to the Brennan Center were located through a search of emails from NYPD personnel who requested such predictions, according to a sworn affidavit by a city attorney.

Rachel Levinson-Waldman, a staff attorney at the Brennan Center who led the effort to obtain NYPD's predictive policing records, said that the system's inability to archive predictive inputs and outputs would impinge on future efforts to independently audit the forecasting algorithms.

Without that information, which is standard for virtually every sort of law-enforcement software, “it will be difficult to assess whether the system is effective or leading to unintended outcomes, and the design effectively avoids this level of scrutiny,” said Levinson-Waldman, who views the NYPD's decision not to store input or output data as a “deliberate choice” rather than a flaw or oversight.

“The only way to test for bias is to have an open system and allow people to kick the algorithmic tires. NYPD's constant fight to withhold data from the public should be a red flag to anyone who cares about evidence-based policing,” said Albert Fox-Cahn, the executive director of the Surveillance Technology Oversight Project.

Assistant Commissioner for External Affairs Devora Kaye pointed to NYPD's presentation of its crime forecasting work at the 2016 INFORMS Conference on Business Analytics and Operations Research and the publishing of an academic white paper the following year to argue that it has more than forthcoming about the nature of its predictive policing work.

“The Department has publicly described these algorithms in great detail, so that experts and the public can review how they work,” said Kaye.

In response to queries from The Daily Beast, Assistant Kaye said that the only data used to generate predictions are complaints for seven major crime categories, shooting incidents, and 911 calls for shots fired. “The algorithms do not use enforcement data, such as arrests and summonses, or quality of life offenses,” she said, or sensitive information such as the name, race, gender, and age of people involved in incidents.

NYPD spokespeople stated that any uniformed officer or civilian crime analyst can generate predictions.

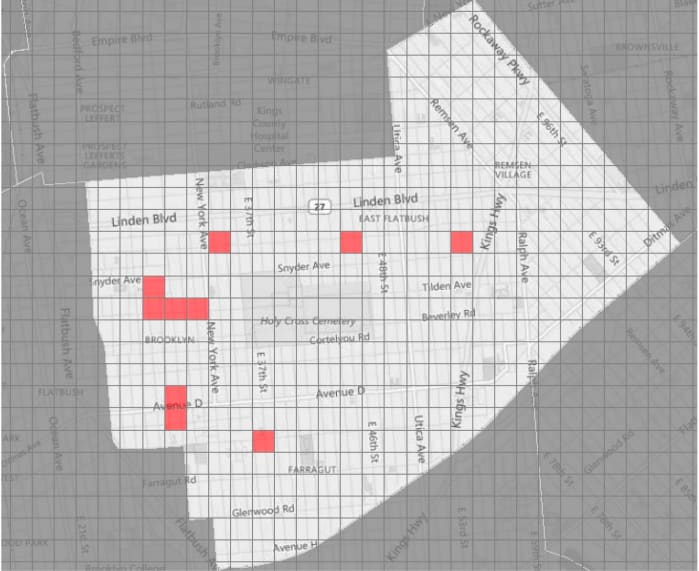

The predictive maps produced by NYPD's in-house algorithm appear as highlighted boxes on a grid map of Brooklyn's 67th Precinct in East Flatbush, as well as the two the 19th and the 23rd Precincts on Manhattan's East Side. Each highlighted box represents areas where past reports of crime have taken place, and where future incidents are likely to occur, per the software's calculations.

The hundreds of prediction maps obtained by the Brennan Center show that the NYPD has been running crime forecasting calculations since at least December of 2015, where personnel at the Upper East Side's 19th Precinct began requesting forecasts of likely locations for burglaries and car thefts. Information about the officers asking for the data, the historical crime reports used to draw up the prediction, and complaint numbers were redacted, making it almost impossible to discern who asked for the forecast, what specific incidents generated the prediction, and what , if any, criminal cases resulted.

While the department would not say how many precincts currently use the predictive policing tool, or how many predictions have been generated to date, it did confirm that eight members of the NYPD had email subscriptions to forecasts from its internal system—and that any uniformed officer or civilian crime analyst can generate predictions.

While the department has not promoted its use of predictive policing with the public, a January 2017 academic paper by four senior department officials used an anecdote from a North Brooklyn precinct about the Domain Awareness System to buttress the case for predictive policing's positive impact on officer deployment for anti-crime assignments.

According to the paper, a sergeant in Brooklyn's 83rd Precinct used NYPD's predictive algorithm to identify potential burglary targets, and assigned a team of cops to monitor a specific area. “The algorithm highlighted a region approximately three square blocks in size,” the excerpt reads.

“After two hours of surveillance, the team observed and apprehended an individual actively engaged in burglarizing a basement in that region; the individual was charged with burglary in the third degree. Without predictive policing, this team could have been placed somewhere else in the precinct and not made the arrest.”

Despite the NYPD's assertions that predictive algorithms are only helping to direct officer deployment and do not take the human element out of policing, some activists believe that the opacity around the project and the NYPD's use of historical crime data that includes millions of stop-and-frisk-induced encounters will invariably taint the program, if it has not already done so.

Fox-Cahn of STOP said the new information about the NYPD's crime forecasting strategies confirmed his long-held suspicions about the department's secretive algorithms.

“They're digitizing the legacy of stop-and-frisk,” he said.” “This is effectively math-washing racially biased policing practices.”

While the documents obtained by the Brennan Center do not provide information about what data sets are used to generate predictions, information from NYPD's shooting predictions and a 2016 pilot program raise questions about both the accuracy of the data and the use of non-law enforcement socioeconomic indicators as potential indicators of crime.

NYPD's shooting predictions from the 73rd and 67th precincts include, along with reports of shots fired called in by members of the public or police officers, included multiple notifications from gunshot detectors set up in neighborhoods around the city by ShotSpotter Inc, a California company that sells its sensors to law enforcement.

Aside from concerns that ShotSpotter's microphones are perpetually recording all sound in their vicinity, the technology's accuracy and efficacy has been repeatedly challenged. Most recently, the city of Charlotte, N.C., canceled its $160,000 contract with ShotSpotter, citing the technology's lack of utility for crimefighting. Though ShotSpotter claims they use proprietary filters to accurately detect and report gunfire, their sensors have picked up plane crashes, fireworks, and vehicle backfires in the past.

The presence of gunshot notifications from ShotSpotter—which are not confirmed instances of gunfire—raised alarm amongst researchers who study predictive policing who noted that gunshot detectors are concentrated in neighborhoods and locations where the NYPD is concerned about either the risk of terrorism, or where shootings are higher than average.

That creates a feedback loop said Richardson, an as predictions are generated, at least in part, by unverified reports of gunfire not supported by ballistics, witnesses, a report of a gunshot victim, or the recovery of a firearm: “It's just data in these areas which will reinforce their views on gun violence, which will justify the use of that technology.”

The company did not respond to requests for comment. After this reporter asked about ShotSpotter, Kaye, the NYPD spokeswoman, told The Daily Beast that the department had discontinued using the company’s alerts to predict gunfire.” (ShotSpotter itself has doubled down on crime prediction. Last year, the company acquired Azavea’s Hunchlab crime forecasting software, which it renamed ShotSpotter Missions.)

While the NYPD has kept its own inputs a secret, emails and presentations from two private firms involved in a 2016 predictive policing pilot—KeyStats and Azavea—show that both unsuccessfully sought to bring in datasets from outside NYPD and even the criminal justice system to generate crime predictions.

Among the data discussed by both KeyStats and Azavea were information about income distribution, the percentage of state or federal assistance recipients in a geographic area, “the prevalence of renters,” the number of single family households and the distribution of public versus private transportation in a neighborhood. Also requested by Hunchlab specifically were information from corrections, parole and ICE that might be able to show information about “known offenders,” indicating that company sought to develop—or has developed—an individualized crime prediction model. In addition, KeyStats requested information about “place of birth,” marriage and divorce status in a neighborhood, school enrollment, educational attainment, and “individuals predisposed to crime.”

NYPD also provided the companies involved in the pilot program with historical crime data and “additional data layers relevant to crime risk: liquor licenses, facility locations, etc,” according to data-sharing agreements released to the Brennan Center.

“One of our biggest concerns stems from the NYPD’s apparent willingness to contemplate using economic and demographic datasets to try to refine their policing models,” said Rachel Levinson-Waldman of the Brennan Center. “It’s possible that there are correlations between these data and some types of crime, but we should be careful to consider the broader implications of using information like this to inform policing decisions,” she said, pointing out that the use of such data could contribute to deepened racial profiling.

“What happens in gentrifying neighborhoods is you tend to see a spike in police reports for certain types of behavior,” said Kristian Lum of the Human Rights Data Analysis Group. ”Previously someone hanging out in front of your house was OK… Now that results in a police report.”

A bill that would require public disclosure and debate of the department's surveillance equipment and software, the Public Oversight of Surveillance Technology act, is struggling to make headway in the city council amidst opposition from Mayor Bill de Blasio and Police Commissioner James O'Neill, Bratton’s pick to succeed him. Council Speaker Corey Johnson has remained neutral on the bill, despite supporting a previous iteration two years ago.

A separate committee set up to investigate the use of automated decision-making systems by city agencies has reportedly been stonewalled for information since its inception and is on the point of collapse.

O'Neill has vociferously defended his department’s use of surveillance tools like facial recognition, which is in the process of being banned in a number of West Coast cities, most notably San Francisco and Oakland. In a New York Times oped last month titled, How Facial Recognition Makes You Safer, he concluded that “It would be an injustice to the people we serve if we policed our 21st-century city without using 21st-century technology.”