Can a candidate repeatedly wash out in debates and still win a presidential nomination? We’re about to find out.

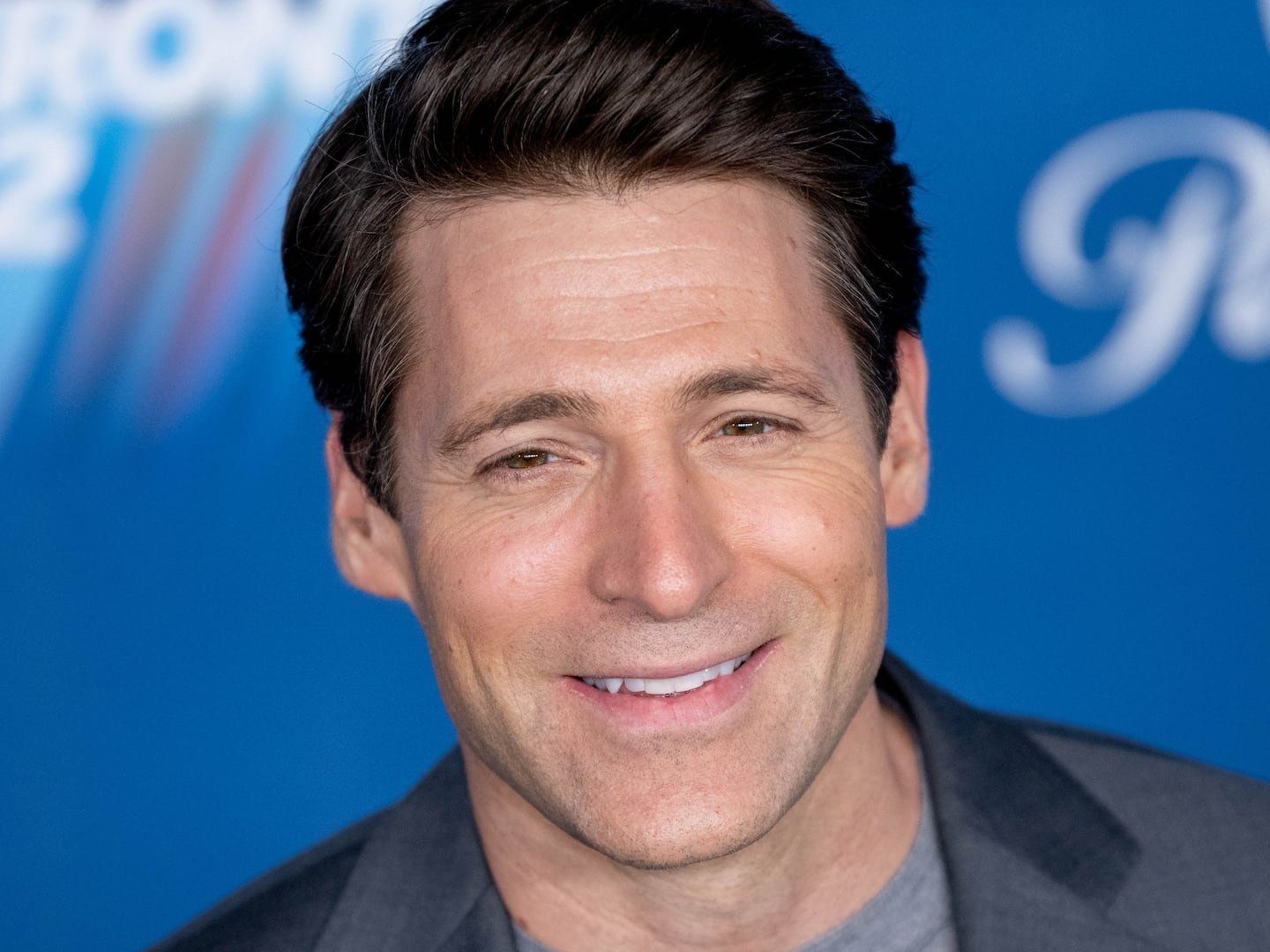

Rick Perry and his team are opening a new campaign chapter of policy speeches, TV interviews, and (eventually) TV advertising to try to revive the Perrymania that greeted his entry into the race two months ago. Whether you call it a natural evolution (as his campaign does) or a midcourse correction on screeching tires, it’s not at all clear that Perry can reverse the impression left by four damaging debates. And that could become five unless he breaks his pattern at Tuesday night’s bout in Las Vegas.

Bewilderment is the prevailing reaction to Perry’s fix. He went into his first debate a frontrunner, “very much in control of his destiny,” says Steve Schmidt, who managed John McCain’s 2008 campaign and is neutral this year. But Perry’s debate performances have visited “grievous damage” on him and “imploded his campaign,” Schmidt said in an interview. “They have pretty conclusively demonstrated that he wasn’t prepared for a presidential race. And once that narrative has set itself, it’s difficult to unwrap.”

Perry has been following his own puzzling timetable. He muffed the first four debates while tending to his fundraising, offered a partial economic plan three days after a debate on the economy, and largely stayed off TV until Friday—when he did five network interviews, more than during his entire candidacy before then. His spokesman, Mark Miner, calls debates “a fraction of the political process,” important to pundits but not to voters in early primary states who want to see Perry up close and hear his ideas. “You can’t do that in a one-minute answer and a 30-second rebuttal,” Miner told me.

But as Perry’s abrupt fade has shown, debates really can matter. They are pressure cookers that often illuminate the character and abilities of even the most scripted candidates. In a larger sense, they can reinforce storylines, as in 1992, when George H.W. Bush looked at his watch and seemed unsympathetic to a woman asking about the economy. They can also change storylines, as when Ronald Reagan’s steady, genial presence undercut his reckless cowboy image.

And debates can create storylines, as has happened repeatedly already this year. When Tim Pawlenty backed off an attack on Mitt Romney, he was instantly deemed lacking in backbone—a single debate moment that dogged him until he left the race. Debates have also established Romney’s professionalism, elevated Herman Cain to a contender, and turned Perry into an underdog.

Democrats are frustrated at this turn of events for at least two reasons. One, polls suggest Perry might be easier to beat than Romney, so they’d like for him to be doing better in the nomination race. And two, Perry is doing a bad job of softening up Romney. So bad that top Obama campaign strategist David Axelrod took on that role himself on a recent press call, pointing out changes in Romney’s stands on various issues and urging reporters to fill the scrutiny gap. “Governor Perry has made some halting efforts” to highlight Romney’s reversals, Axelrod said, “but he hasn’t exactly gotten the gun out of the holster.”

None of this is particularly surprising if you consider that during his long political career in Texas, Perry agreed to very few debates. That may have seemed like a clever idea at the time, says Alan Schroeder, author of Presidential Debates: Fifty Years of High-Risk TV, but it’s backfiring now. “If you have aspirations beyond your state, you want to have a lot of practice,” he told me.

Schroeder says he is “mystified” by Perry’s failure to release an economic plan before the Oct. 11 debate on economic policy. “You know you’re going to be asked about economics. To answer that you’ll be putting out a plan later this week is really strange,” he says. “People were just waiting for Rick Perry to seize his moment. He had a perfect opportunity to take advantage of that, and he didn’t.”

At the very least, says former Gore 2000 press secretary Chris Lehane, Perry should have been armed with news nuggets to drop into the mix and crisp replies to tough questions that he’s fielded before. To him, Perry seems entirely too casual about debates, as if “he woke up Sunday morning and strolled down the driveway” to prepare. “I fully expect him to show up in a bathrobe next time with disheveled hair,” Lehane joked in an interview.

Maybe Perry will show up that way in a Saturday Night Live caricature. In real life it’s too soon to write him off. He still has money in the bank ($15 million), appeal to evangelicals, executive experience, and a record of creating jobs. He says his new energy plan—tantamount to “drill, baby, drill” on steroids—would create 1.2 million jobs, and he plans to announce more economic proposals in an Oct. 25 speech in South Carolina.

Merciless reviews from fellow conservatives suggest that these late-breaking initiatives are too little, too late. “Perry has done nothing but shoot himself in the foot he’s had lodged in his mouth for six weeks,” wrote New York Post columnist John Podhoretz. Byron York of The Washington Examiner said the lesson of Perry’s candidacy is “think before you run”—about national issues, not about how to raise big money. National Review’s Jim Geraghty said Perry “stumbled through three debates so badly that by the fourth he expressed exasperation that everyone around him keeps arguing over ‘whether or not we are going to have this policy or that policy,’ and nobody even blinked when he said he was bothered by the presence of policy debates at a policy debate.”

If Perry confounds expectations, his history of avoiding and blowing debates would haunt him as the GOP nominee. Retail politicking doesn’t get the job done in the rush and sweep of a general election. At that stage, nationally televised debates seen by up to 80 million people are a major factor. Picture it: President Obama vs. a Republican who won his nomination despite a string of cringeworthy debate performances. If that doesn’t strike fear in Republicans, Schroeder says, it should.

Debate damage through the years can be tracked in the ups and downs of Gallup polls. George W. Bush’s lead over John Kerry in the Gallup poll dropped from 11 points before their 2004 debates to 3 points afterward. In 1960, John F. Kennedy went from trailing Richard Nixon by 1 point to leading him by 4 points. Reagan went from down 3 points to ahead by 3 points over Jimmy Carter in 1980.

In 2000, Al Gore had an 8-point lead over George W. Bush before the first debate. But then there were the sighs (loud and patronizing) and the makeup (orange and weird) and the three different personalities Gore displayed in three different debates. When they were over, Bush had a 4-point lead. “Al Gore wasn’t president in no small part because of the debates,” Lehane says. In 2008, polls found Obama had bested McCain in their face-offs. “His victories in those debates began to solidify his lead and made it impossible for there to be any sort of McCain comeback,” Schmidt told me.

Perry has got to be praying that Republicans aren’t thinking so far ahead. It’s either that, or prove he’s got what it takes to challenge a president.