The first Republican primary debate is fast approaching, scheduled for Aug. 23 in Milwaukee, and hosted by Fox News.

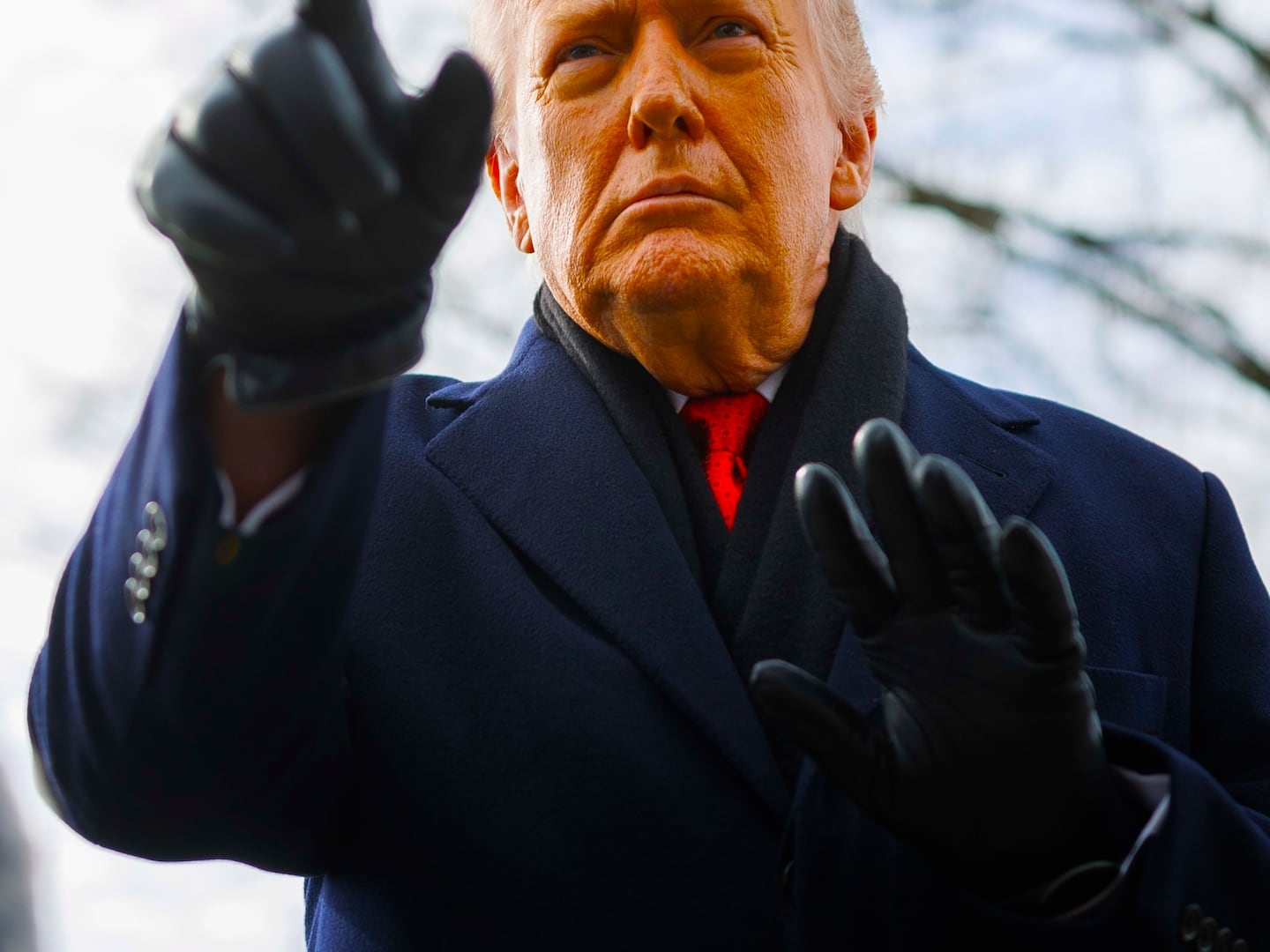

Former President Donald Trump, who is currently running about 40 points ahead of his nearest competition, has been suggesting he might not show up.

Other candidates have been scrambling to meet the criteria for inclusion: hitting at least 1 percent in a sufficient number of state or national polls along with having at least 40,000 campaign donors. Whoever ends up participating, there will be no shortage of drama. One source of drama comes not from the candidates themselves but from the Republican National Committee, which has increasingly inserted itself into a process traditionally run by journalists.

Polling and donor thresholds were first adopted by the RNC in 2016, but for the 2024 cycle, the party has also imposed a new requirement. Candidates must sign a pledge that they will support the Republican nominee, no matter who it is, and additionally to not run as a third-party candidate.

The RNC’s pledge is bad on the merits, politically counter-productive, arguably illegal, and candidates and the networks should stop enabling it.

You Got a License for That Debate?

Until recently, the national party committees had no part in primary debates. Debates were organized by media outlets, typically a TV news channel, sometimes in collaboration with state-level partners such as the Des Moines Register or the New Hampshire Union Leader. Within applicable legal requirements (more on that in a moment), debate sponsors set their own criteria for which candidates were invited.

But starting in 2016, both parties began to use their power over the nomination process to assert control. Conventional wisdom set in that the parties, as such, were not being well served by the status quo.

On the Republican side, there was a sense that the 2012 primary debates had exposed Romney to too many attacks and pulled him too far to the right, damaging his prospects in the general election. For Democrats, memories were still fresh regarding the never-ending Obama-Clinton debates in 2008, which also devolved into harsh negativity. There were widespread complaints that there were simply too many debates, including too many candidates with little-to-no support.

The NBC-Facebook Republican presidential candidates debate between (L-R) Rick Santorum, Mitt Romney, and Ron Paul at the Capital Center for the arts in Concord, NH on Jan. 8, 2012.

Rick Friedman/Corbis via Getty ImagesThe RNC and DNC only had one lever to pull: the delegate rules for the national convention. Both parties adopted their own schedule of permitted debates, assigning which channels would host them, and set their own rules for how candidates could qualify.

To force compliance, candidates would be stripped of their delegates if they showed up at any unsanctioned debates. In effect, the policy is a ban on any two or more candidates appearing on the same stage at the same time without a party permission slip.

The media sponsors of debates were, unfortunately, acquiescent in this power grab. The limited number of approved debates made each one more valuable, and the networks were able to outsource the contentious process of setting inclusion criteria. Pushback from the candidates was also minimal. But both the media and the candidates were short-sighted, neglecting the long-term implications of this scheme.

It’s My Party…

At first, the party debate rules did not seem very objectionable. The number of debates was reduced, but not that dramatically. The inclusion criteria seemed reasonable, based on a mix of polling thresholds and number of donors. The latter, in particular, incentivizes candidates to help build the party’s small donor lists. And so it went in 2016, a competitive open race for both parties, and the debates played out with little noticeable difference from prior cycles. In form, at least, if not in substance.

Republican presidential candidates Ben Carson, Marco Rubio (R-FL), Donald Trump, Ted Cruz (R-TX) and Ohio Gov. John Kasich (L-R) at the Republican National Committee Presidential Primary Debate at the University of Houston, Texas, Feb. 25, 2016.

Joe Raedle/Getty ImagesIn 2016, the RNC circulated a pledge to support the nominee and pressured candidates to sign. But this wasn’t tied to debate inclusion or delegate penalties. The only consequence at stake was political criticism. Whether Trump would sign became a minor story, and at the first debate he was attacked by his opponents for his refusal. He ultimately did sign, and of course in the end, it didn’t matter. Instead, it was Trump’s opponents who were locked in to a promise to support him.

For 2024 (there were no Republican debates in 2020), the RNC was determined to make the pledge more than a suggestion. Alongside the polling and donor thresholds, they added a rule that no candidate could debate who didn’t pledge to support the nominee, no matter who it was.

There is something farcical about the whole exercise. A number of candidates are strongly anti-Trump and have balked at the implication that they must support him if he wins the nomination. Likewise, Trump himself has indicated he’d be unlikely to back anybody else if he somehow loses the primary.

It’s also unlikely the committee could stick to its delegate-stripping punishment if any major candidates called their bluff. If Trump and DeSantis decided to do a head-to-head debate, would the RNC really throw them both out of the race? Say no Trump or DeSantis delegates will be seated at the convention? It’s obviously an empty threat, at least for any candidate with substantial support.

The media have covered the back and forth over the pledge but had little to say about their own central role in it. None has objected to the RNC’s pledge rule, even though it amounts to the party hijacking their programming. And it is their programming.

The RNC doesn’t buy the cameras, rent the venue, pay the moderators, or broadcast the event. Fox News and CNN and MSNBC and ABC do that. And they’re the ones on the hook not just for the political consequences, but also running afoul of the law. It’s their show and they should act like it.

US Republican presidential candidates Marco Rubio and Donald Trump in the CNN filing room during the Republican Presidential Debate at the University of Houston, Texas, Feb. 25, 2016.

Thomas Shea/AFP via Getty ImagesThere Are Rules Here

The parties have more or less absolute control over the delegate selection process, which ultimately controls the presidential nomination. They are, in this respect, private organizations free to set their own internal rules. Though the primaries are run by state governments under state laws, how the parties use those results to allocate delegates (or if they do so at all) is up to the parties. The national committees have used this power, with mixed results, to punish states holding primaries outside of the party’s preferred schedule.

Debates are a different matter. As a consequence of campaign finance laws, the Federal Elections Commission does set certain rules. This is necessary to distinguish debates from electioneering communications, or in other words campaign ads, which are subject to various regulations.

Unlike campaign ads, debates may be funded by corporations, so long as those sponsors do not “endorse, support, or oppose any candidate or party.” These sponsors can not be “owned or controlled by a political party, committee, or candidate.” Additionally, debates “must be structured so that it does not promote or advance one candidate over another.”

Most importantly, debate sponsors must use “pre-established objective criteria” to decide which candidates to invite. This means rules have to be based on objective measures of a candidate’s support, not subjective political biases about which candidates or positions the debate hosts prefer. Anything else would be, in effect, an ad for the chosen candidates rather than a neutral debate.

Underscoring the point that debate sponsors can’t resort to politically biased exclusion, there’s even an explicit carveout clarifying that primary debates can be limited to candidates running for that party’s nomination. An obvious exception, but one that implicitly affirms how sweeping the general rule otherwise is.

Requiring candidates to pledge fealty to a substantive political position is not using objective criteria. It’s putting a thumb on the scale based on the content of a candidate’s message, not how much support they have. Even aside from legal concerns, that’s not proper as a matter of journalistic ethics.

If challenged, the networks would surely say they have no position on if Chris Christie should endorse Donald Trump next year. But in fact, they’re letting themselves be bullied into exactly that, by refusing to let Christie appear on their broadcast unless he agrees.

News desks and media executives should carefully consider how far they’d let this game go. If the party committees can require a pledge for one political position, what others could they require? If the RNC demanded it, would CNN agree to invite only candidates who have signed a pledge to oppose tax increases? Would Univision (currently slated to co-host the second debate) go along with it if the DNC said pro-life candidates must be excluded?

An Unpatriotic Pledge

Legal and ethical concerns for journalists aside, the RNC’s pledge is objectionable on the merits. It’s also bad politics. Candidates can say they’ll support the eventual nominee if they want, but it’s ill-advised to do so in absolute, unconditional terms as the RNC requires.

Generally, we expect our potential presidents to at least pretend they are willing to put the best interests of the country above all other concerns. The pledge is an explicit inversion of that principle. It requires candidates to announce they’ll put party over country, even if they truly believe the party has nominated somebody who’d be a terrible president. There is no civil virtue in that, not even in pretense.

While most attention has focused on Trump for obvious reasons, the point is generally applicable. Trump himself would be equally correct in refusing, on the same principle.

The pledge is a completely open-ended commitment, a promise to back literally anybody the GOP might nominate. It’s not hard to imagine extreme scenarios where this would be completely unacceptable, even unpatriotic.

Bound to Backfire

For all these problems, the pledge doesn’t accomplish its intended purpose. Partly because it’s something of a joke, so obviously unenforceable.

There are no serious consequences for a candidate who doesn’t abide by the pledge after they’ve lost the primary. While there are real downsides to refusing to support the party’s nominee, an unpopular move with the party’s base, the pledge doesn’t add anything to that. Nobody really cares about breaking the promise as such.

The RNC’s gambit is also counter-productive to their own stated goals: uniting the party and avoiding a spoiler candidate. The pledge not only requires supporting the nominee, it explicitly includes promising not to run as an independent or third-party candidate. But this seriously misunderstands how the primary works and why it results in the party unifying around its chosen candidate.

The first-past-the-post electoral system is the biggest reason why America has such a uniquely strict two-party system, with little place for serious third-party candidates. But it’s not the only factor helping entrench the Republicans and Democrats against electoral competition. The institutionalized primary is also an important part of the equation, subsidized as it is by state-run elections provided for the parties, something unheard of in other democracies.

It is precisely because political minorities within each major party coalition can run in the primary that they are less likely to run outside of the party. Even for candidates with little hope of winning, the primary allows them to have their say, rally their like-minded voters, attain national prominence, and have some influence on the direction of the party.

Instead of encouraging such candidates to run as Republicans, the RNC’s policy attempts to push them out. The pledge rule makes it more likely, not less likely, that a disgruntled Republican politician will bolt to run third-party. For a rational political actor, the pledge makes it more attractive to not run in the primary, to the detriment of the party’s own self-interest.

Candidates should refuse to sign the pledge, both on principle and because it’s bad politics. Media sponsors should refuse to disinvite otherwise qualified candidates who refuse to sign the pledge. The FEC’s rules for debates should be taken seriously as long as they’re on the books. And the RNC should give up on trying to hand down political diktats about what candidates must say and what positions they must take.