When we gaze into the vast night sky from our terrestrial home, space certainly seems like an overwhelmingly wild and desolate place: an empty plain primed for settlement. When Star Trek debuted in the ’60s and began calling space “the final frontier,” it was in the midst of a geopolitical race to the moon with the Soviet Union. “Final frontier” became synonymous with a spirit of space expansion that is deeply, perhaps distressingly, American.

Now, with an increasing number of billionaires whipping out spaceships for their own public rocket-measuring contest, a growing movement in the space industry inspired by de-colonialist ideas wants to ensure that places like Mars don’t become the next “New World” for people in power to conquer and trash. In order to avoid repeating our historic mistakes, these scientists and policy makers argue that humans need to take a hard look at the laws we’ve established here on Earth before we boldly go where no person has gone before.

“The three dominant myths of space governance right now are that there’s no history, no victims, and no law,” Cris van Eijk, a space policy adviser with the International Astronomical Union, told The Daily Beast. Far from being an empty, ahistorical void, space is chock-full of resources, scientific opportunities, and man-made artifacts—including a rapidly accumulating pile of orbital junk. Far from being lawless, it is a place with a carefully crafted and evolving legal framework. And far from being victim-free, humanity’s actions in space profoundly impact daily life on Earth—both for better and for worse.

For Britt Duffy Adkins, an urban planner at the University of Southern California, the need for a de-colonial mindset became apparent as soon as she started attending space policy conferences as a graduate student in 2018.

“I was shocked,” she told The Daily Beast. Speaker after speaker presented their idea for a Martian colony, but none seemed interested in sustainability development or inclusion. “It felt like we were just taking a page out of some very dated history book.”

Adkins looked around, and couldn’t find anyone having the kind of discussions about sustainable infrastructure and development in space that she was looking for outside of very niche circles. So in 2020 she founded Celestial Citizen, a space media company dedicated to furthering conversations around inclusivity, equity, urban planning and research in space. “I’m very opposed to the idea of going and planting flags,” said Adkins.

Van Eijk echoed those feelings. In an essay published last year in Volkerrechtsblog, an academic blog about international law, he called out SpaceX founder Elon Musk for sneaking a metaphorical flag into the terms of service for Starlink, his company’s internet service that seeks to connect people around the world by launching and operating 42,000 satellites in orbit. Buried in a section called “Governing Law” is a little paragraph claiming that future Starlink satellites on Mars will be subject to California state law—the same state where Musk happened to live at the time. Under international law, this could be interpreted as setting a “critical date,” a ticking clock counting down to a point after which other entities can no longer dispute a sovereignty claim.

“In the future at some point, if we’re looking back on this as to when did SpaceX establish a claim on Mars, this would be part of that evidence,” van Eijk said.

That wasn’t the first time Musk made a contentious claim about Mars. In January of 2021 he announced a plan to entice working-class folks to his future Mars colony; non-wealthy settlers would be assigned jobs in order to pay off their travel debt. Critics quickly pointed out that this sounds a lot like indentured servitude. It’s also a concerning example of what social scientist Linda Billings calls “the ideology of space colonization and exploitation.”

“How do you quit your job in space?” Billings told The Daily Beast. “You can’t just get in your car and go home.”

Billings, a longtime NASA consultant, started out as a journalist covering space business and policy under the Reagan administration. However, she eventually became disenchanted with what she felt was the government’s Manifest Destiny approach to the space sector.

These days, Billings believes that human beings simply aren’t ready to settle in space yet. To try, she said, would risk bringing along an environmentally destructive mindset, extracting resources at an untenable rate and basically just exporting our current problems elsewhere.

But while she’s against settling places like the moon or Mars, she isn’t against exploring them. And she said we already have a perfectly good framework in place for that.

The Outer Space Treaty is widely considered the foundational document for space law. Drafted in 1966 (the same year Star Trek first hit the airwaves) by the UN and initially signed by the United Kingdom, United States, and the Soviet Union, the agreement establishes space as an international commons, “the providence of all mankind.” It explicitly prohibits things like military maneuvers in space or ownership of territory beyond Earth’s atmosphere. At least 111 countries are bound by its terms, and another 23 are signatories but have not yet ratified it.

But some legal experts think that the Outer Space Treaty doesn’t go far enough. “It is insufficient, because it’s a very specific law,” John Tziouras, a space policy consultant at Aristotle University of Thessaloniki in Greece, told The Daily Beast. When it was first written, there were only two countries—the United States and the Soviet Union—who could get to the moon, as part of a geopolitical project. The idea of a single, SpaceX-style company sending people to Mars was unthinkable. But now we have private corporations whose goals are to specifically send people to these worlds to establish permanent communities.

Tziouras advocates for the world to model its space-faring approaches on a different document: the Antarctic Treaty. Written in 1959, seven years before the Outer Space Treaty, the Antarctic Treaty also prohibits military action and private land ownership on, obviously, Antarctica. But crucially, it also outlaws resource extraction—an activity that is technically allowed under the Outer Space Treaty. To avoid private companies or nations extracting resources from celestial bodies like Mars or asteroids, he thinks that space policy needs to establish clear boundaries.

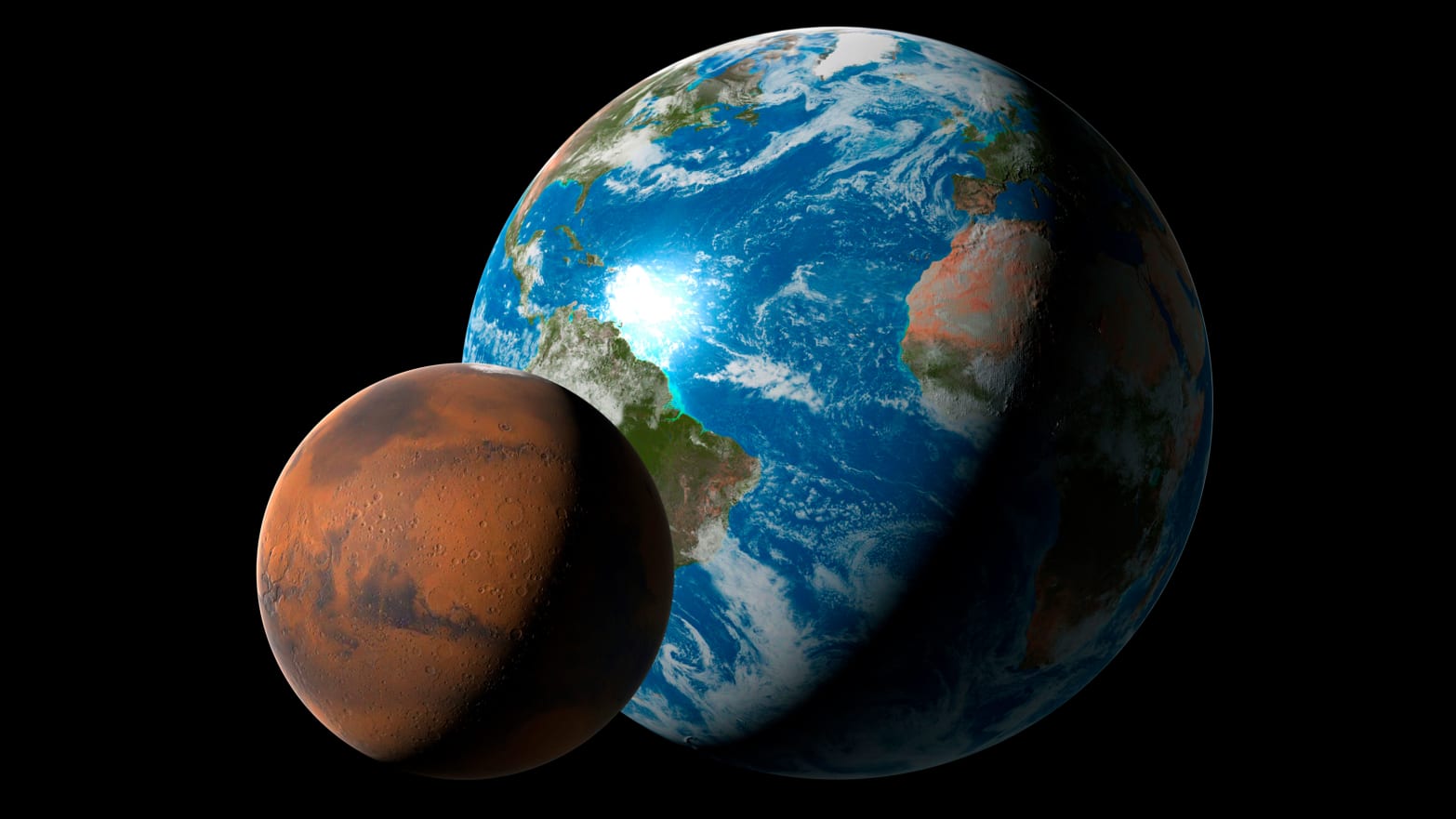

Antarctica is a harsh, largely inaccessible yet resource rich environment, much like the surface of Mars. Yet the Antarctic Treaty has provided a solid framework for humans to conduct research there, safely and peacefully, for half a century without any commercial mining. In Tziouras’s view, it makes sense to use it as a basis for humanity’s next great exploration.

Billings countered that this approach could leave too many regulatory loopholes open—after all, while the continent itself has never been mined, the seas around Antarctica have been dangerously overfished. Rather than overhauling the Outer Space Treaty, she favors creating a whole regulatory body to oversee resource extraction. “The treaty has preserved space for peaceful purposes for decades and decades,” she said. “We don’t need to mess with it.”

Others argue that humankind should look beyond legal documents as a way to conceptualize life in space. Instead, they want to transform the culture around space exploration by turning to a different kind of organizing body: grassroots movements.

Danielle Wood, a systems engineer at MIT’s Media Lab with a focus on justice, sustainability and inclusion, believes in the power of social movements to change society. She dreams of melding grassroots activism with policy to craft a healthier future in space. “I spend a lot of time studying the activism and struggles of communities that have experienced oppression,” she told The Daily Beast. “Obviously, there’s a lot of work to do, but we have made some progress.”

To Wood, the very idea of space as a frontier to be settled is a damaging one. Historically, she said, the U.S. and other colonial powers have used the romantic notion of frontiersman-ship to expand their territory, encouraging individuals to land grab under their country’s flag. But she sees a better way forward; for all its policy imperfections, she cites the spirit of the Outer Space Treaty as a beautiful example of how nations once came together and opted for peace, even during the Cold War.

Instead, Wood wants to push forward space technologies that aren’t designed to help us escape Earth, but rather make it a better place to live. This is already happening through tools like GPS that help us navigate. And space exploration has yielded other major advances, improving communications with satellites, medicine with microgravity research, food shelf stability with more advanced vacuum-seals, and green technology like solar panels. Modern solar power systems owe much of their development to NASA engineers trying to keep satellites running. Studying the atmospheres of Venus and Mars helped scientists on Earth address the hole in our ozone layer. In fact, an important part of de-colonizing space, Wood says, is making all of these technologies available to everyone, equally across the globe.

At 62 miles (100 kilometers) overhead, space is nearer to our rooftops than New York City is to Philadelphia, both literally and figuratively close to home. As humanity moves towards a sci-fi future, it might be time to reframe how we see it: not as a frontier to conquer, but more like a campsite to leave better than we found it.

“If we don’t think that space is a place ruled by law, then we know how that ends,” said van Eijk. “The richest win.”