A special visa program for Afghans who worked alongside U.S. forces in Afghanistan is likely to lapse over objections from a key Republican senator.

Known as The Afghan Special Immigrant Visa program, the program grants protected status to Afghans who were escaping the country precisely because of their association with, and work for, American armed forces. It is authorized until 2021. But advocates have warned that without new legislative directive, the number of visas that can be granted through it will be exhausted well before then.

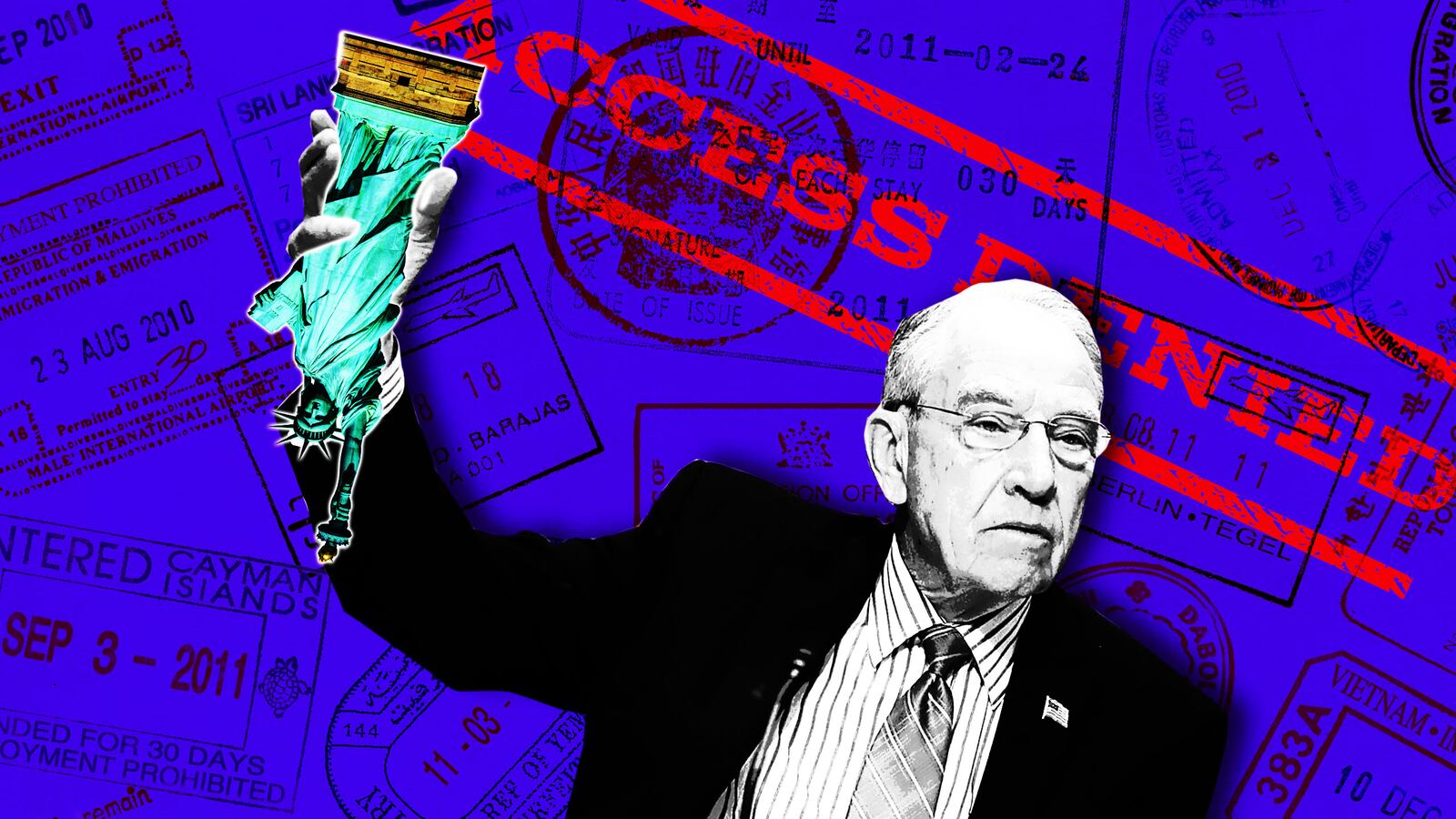

Those advocates had pushed for 4,000 additional visas to be made available in a must-pass defense spending bill. But when that bill came to the Senate floor on Monday night, there was nothing in the final language to bolster the program due to objections from Senate Judiciary Chairman Chuck Grassley (R-IA) over what he perceived to be the program’s lax standards. Because the House version of the defense spending bill did not include the provision either, aides working on the matter have grown highly pessimistic that visa program will survive in the long term.

“It’s in trouble,” said one Senate Democratic aide working directly on the visa program.

The aide noted that when House and Senate negotiators reconcile their respective bills together, lawmakers could try and reintroduce the visa program into the final legislation. But that would be a procedural long shot.

That Congress even got to this point serves as an illustration that the political paralysis over immigration policy has extended beyond the current debate over families crossing the border and into various elements of U.S. foreign policy. Only, in this case, President Donald Trump isn’t the nexus of that paralysis.

The Afghan Special Immigrant Visa program started as a means of getting a yearly allotment of visas for both Afghans and Iraqis who proved they were under threat, held a job that helped with U.S. national security, and were recommended for protection (so as to filter out potential imposters). The Iraqi component ended as the war there drew down. But the Afghan component has persisted, and so have the visas.

Over the years, lawmakers have routinely bickered over how many visas to issue and how stringent the requirements should be for those applying. Old emails provided to The Daily Beast show that Grassley’s office also tried to narrow the scope of the visa program back in 2016. He was joined in that effort by his fellow Judiciary Committee member Sen. Jeff Sessions (R-AL), who routinely warned about the program being abused.

Sessions left the Senate in 2017 to become attorney general. But the administration in which he now serves is not the entity holding up the current debate. In their annual budget request, the president and his team asked for 4,000 visas to be issued under the program.

That’s the number to which virtually every lawmaker has agreed, including the numerous Republican backers, such as Sens. Thom Tillis and John McCain. But according to several Hill sources, Grassley’s office demanded that in exchange for authorizing that many visas, lawmakers included language stipulating that anyone who applies could only be classified as a translator or an interpreter.

The senator’s office declined repeated requests for comment. But Grassley himself told McClatchy that he “just want[ed] some integrity provisions added” to the program.

One Senate policy aide working to secure the visas said the senator’s position was akin to “a constantly shifting set of demands” that is, ultimately, meant to chip away at the visa program. Led by Sen. Jeanne Shaheen (D-NH), proponents decided not to acquiesce.

The result was that no new visas were put in the final version of the National Defense Authorization Act that passed the Senate on Monday night.

Tillis, a member of the Senate Armed Services Committee, told McClatchy that he was hopeful that some extension will ultimately be added when the Senate and House go to conference. Even if it didn’t, he added, lawmakers would “look for other vehicles.”

But the defense authorization bill has been the legislation through which this program has always moved, in part because its cost—$172 million over the course of the next 10 fiscal years—is a drop in the bucket compared to the size of the overall package.

That lawmakers couldn’t bridge their differences over that amount of funding, said the aforementioned Democratic aide, is a “sad state of affairs.”