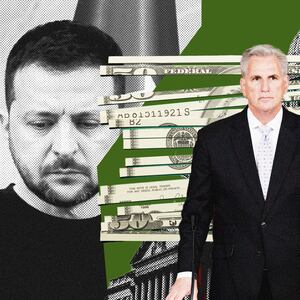

As the United States approaches a deadline on extending the debt limit, Democrats are in a difficult position: They don’t want to default, they don’t want to negotiate, and they don’t trust House Speaker Kevin McCarthy to negotiate.

“To me, that’s an essential element of the case as to why we can’t negotiate,” said Sen. Chris Murphy (D-CT).

“These guys are a bad reality show. McCarthy can’t negotiate, even amongst a group of ideological lookalikes,” Murphy added. “How on Earth is he going to negotiate a deal that keeps his gang together and also draws Democratic votes? It’s a physical impossibility.”

Murphy’s take seems to be a popular one among Senate Democrats. McCarthy’s standing as leader of the House GOP is so fraught, so precarious, that even in the face of a catastrophic economic cliff, Democrats don’t trust his ability to negotiate in good faith, nor to actually deliver on his promises.

“There’s no question in my mind that this speaker is in a much weaker position than John Boehner was not that long ago. And that ought to be a four-alarm concern for everybody who wants to land this economic plane safely,” said Sen. Ron Wyden (D-OR).

“He sold his soul when he got to be speaker, so I don’t know what his capabilities are. We’ll find out,” Sen. Jon Tester (D-MT) added.

Not quite his soul—as far as we know—but McCarthy did make concessions in order to be speaker. He had to to appease the conservative wing of his conference that held up his nomination over 15 votes.

That same conservative wing threatens now to hold up any sort of compromise on the debt limit—at least one that could win approval from both the White House, the House, and 60 members of the Senate.

Conservatives want budget cuts and policy riders galore, including things like striking clean-energy credits and blocking student loan forgiveness.

But when McCarthy put a bill to raise the debt limit on the floor recently that was jam-packed with conservative priorities, he still lost four of his own members—and got zero Democratic votes.

If he’d lost one more, the bill would have been dead altogether. (It’s dead-on-arrival in the Senate, anyway.)

McCarthy’s situation isn’t exactly instilling confidence that he can strike a deal that would pass the Senate and the House. McCarthy has to appease the conservatives who are dangling the sword of Damocles—read: the recently reinforced motion to remove the speaker—over his head. And he has no real obligation, other than an obligation to the country and its economy, to find a debt limit deal.

But plenty of Republicans don’t see much incentive to strike a deal. If there are economic consequences for not raising the debt limit—as there almost certainly will be—they believe voters will hold Democrats responsible. And McCarthy isn’t exactly famous for putting the good of the country over politics.

After proclaiming that then-President Donald Trump “bears responsibility” for the Jan. 6 attack on the Capitol, McCarthy has spent two years downplaying the insurrection and running interference for Trump. After saying in June 2016 that he truly thinks Vladimir Putin pays Trump—”swear to God”—McCarthy has spent the next roughly seven years cozying up to Trump. And after saying there were certain red lines he wouldn’t cross in order to secure the speaker’s gavel, he caved on almost every conservative demand.

McCarthy did the same with the House’s debt limit bill, passing severe cuts to Medicaid and food assistance. (The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities recently projected that the House’s debt ceiling proposal would kick 10 million people off Medicaid and 1 million people off food assistance.)

A person familiar with McCarthy’s thinking also recently told The New York Times that the speaker’s instinct is to do the opposite of whatever former speakers like John Boehner would do. Where Boehner knew he would eventually have to pass a largely clean debt limit increase—like he did in 2013 during a government shutdown with almost all Democrats and just 87 of 232 Republicans—McCarthy seems content to let the standoff continue until Senate Democrats at least get serious about major spending cuts.

Meanwhile, the Senate isn’t coming to the negotiating table. And the White House is still demanding a “clean” bill to raise the debt ceiling. Senate Republicans aren’t really facilitating any solutions, either. Instead, they’re parroting calls from the House GOP for negotiations to get started between Senate Democratic leadership and House Republicans.

And, at least publicly, Senate Republicans are posturing that the House is prepared to make a deal.

“We’ve had 11 of these recently—and I don’t know if that’s 11 in 11 years or 22 years—but we’ve had 11 of them and six or seven of them have had debt limit connected with it,” said Sen. Chuck Grassley (R-IA) said of a potential deal. “So based upon history and where we are today, yes, I have confidence it can be done.”

Approximately a dozen Senate Republicans, led by Sen. Rick Scott (R-FL), gathered outside the Capitol Wednesday to echo that call. Scott said he was “proud” of the House GOP for passing its bill.

Negotiations could start in earnest on May 9, when the “Big Four” leaders of the House and Senate are invited to the White House to meet with Biden to discuss the debt limit.

But staring down a potential stalemate with Republicans—and their own confirmed doubts about McCarthy’s potential to lead—Senate Democrats aren’t exactly offering many immediate solutions. Instead, they’re just blaming the impasse on McCarthy.

“We know it’s a challenge,” said Sen. Ben Cardin (D-MD). “We know how he got to become speaker.”

“But,” Cardin added, “we have to deal with the cards that have been dealt, and we have to figure out a way to move forward.”

Asked how his caucus should grapple with the realities of House Republicans’ demands and conditions, Wyden told The Daily Beast the House was already looking at “various ideas.”

“I’m not gonna—former House member—tell them what to do,” he said.

Altogether, the Senate’s sense of urgency last week was sometimes questionable. With words, they warned the United States was at risk of a catastrophic default. Lawmakers like Tester told reporters Wednesday that passing the debt ceiling will determine whether “this country will remain the best economic and military power in the world.”

“They’re putting all that at risk,” Tester added.

But the Senate’s actions didn’t necessarily reflect that rhetoric. By Thursday afternoon, senators were headed out of town. And now they won’t be back until Tuesday night.

The White House, meanwhile, said last week it’s open to a short-term extension for the debt limit, something that could delay the deadline that experts say could come as soon as early June. Congress did the same thing in 2021 when lawmakers could not come to a long-term agreement on the debt limit, teeing up the current tangle.

That vote, which happened while Democrats had a trifecta of power, landed mostly along party lines. Only one House Republican, now-former Rep. Adam Kinzinger (IL), voted for the measure.

McCarthy’s numbers aren’t looking any better.

“There’s lots of reasons not to negotiate over the debt limit,” said Murphy. “One of which is to not set a precedent that we have to follow, but another is the fantasy land—and which is not believing that there’s any outcome where McCarthy could deliver a result.”