Sex, Deceit, and Scandal: The Ugly War Over Bob Ross’ Ghost

Bob Ross Estate

For decades, Bob Ross has been a soothing presence in a world gone mad. But the real story behind the painter’s life, and especially his afterlife, reveals just as much madness.

Bob Ross is everywhere these days: bobbleheads, Chia Pets, waffle makers, underwear emblazoned with his shining face, even energy drinks “packed with the joy and positivity of Bob Ross!” Whatever merchandising opportunity is out there, kitsch or otherwise, it’s a safe bet his brand-management company is on it—despite his having shuffled off the mortal coil more than 25 years ago.

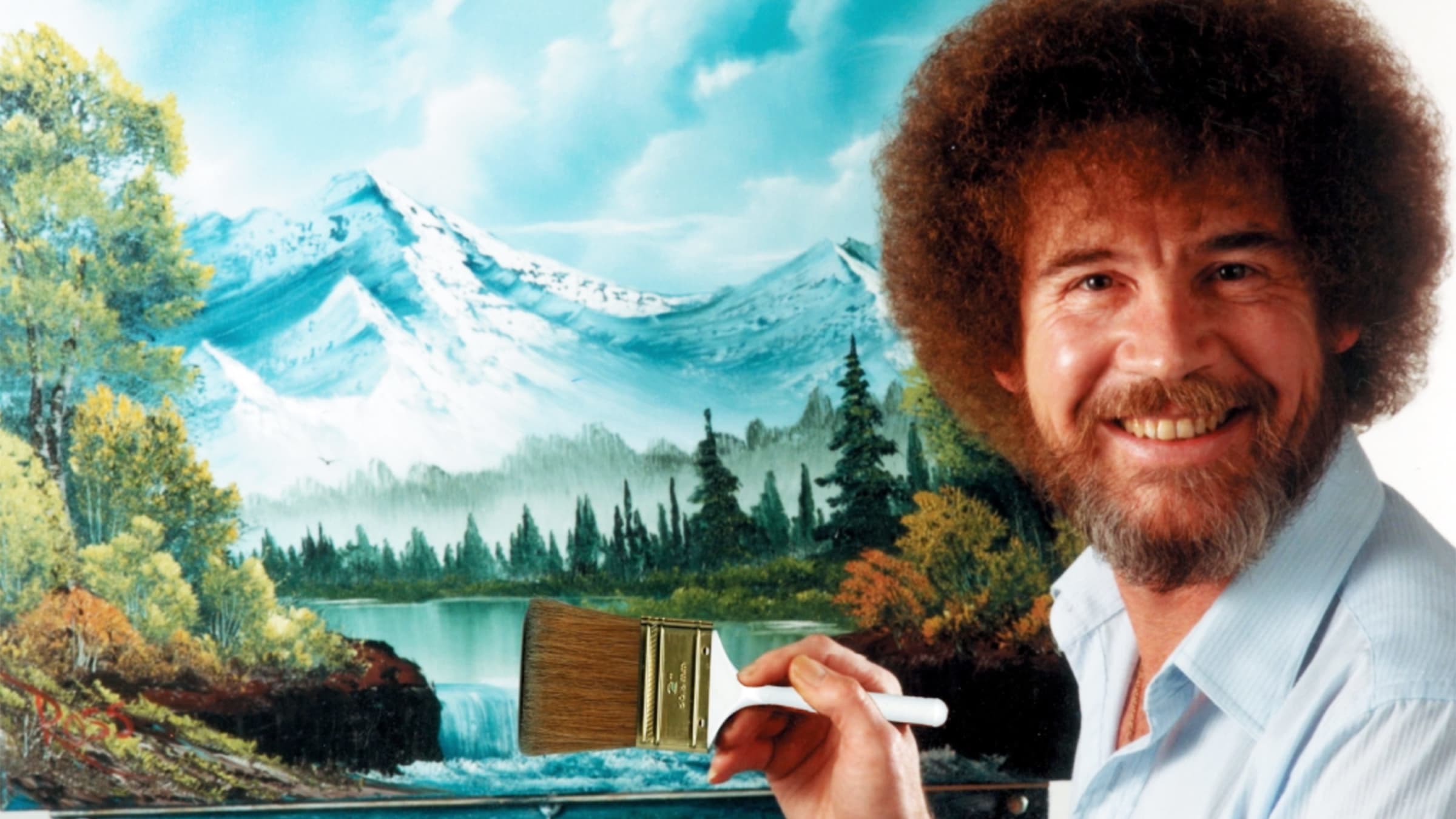

He’s also a smash hit on social media, where he feels more like a Gen-Z influencer than a once semi-obscure PBS celebrity who rose to fame in the 1980s on the back of his bouffant hairdo, hypnotic singsong baritone, and a timeless message about the beauty of the world around us. His official YouTube page has logged close to half a billion views. He’s been satirized by the comic-book anti-hero Deadpool, the world-infamous street artist Banksy, and even Jim Carrey as Joe Biden on Saturday Night Live.

If that weren’t enough, he’s hawking Mountain Dew in a new CGI commercial that’s right on the edge of the uncanny valley, and Netflix has a feature-length documentary about him due this summer by the prolific actor-producer Melissa McCarthy.

Yes, Bob Ross is a beacon of light in an ever-darkening world—an endless stream of soothing bon mots perfectly at home in the meme-and-merchandise internet era.

He was also recently in federal court. Or, to be more precise, his eponymous company Bob Ross, Inc., was. Now run by the daughter of Bob’s original business partners—Annette and Walt Kowalski—Bob Ross, Inc., was defending itself against claims that it had made millions of dollars by illegally licensing Bob’s image over the last decade, expanding far beyond the company’s original core business of selling Bob Ross-themed paints and paint supplies.

The broad contours of the case revolved around the nuances of intellectual property law and were nothing new in the world of legal bickering over celebrity estates. The details, on the other hand, resided in the land of the unbelievable—incorporating deathbed marriages, last-minute estate changes, CIA-style tape recordings, and even a real-life former CIA agent.

It was all made even more bizarre by the plaintiff who filed suit: Bob’s very own son Steve Ross, a long-standing superstar in the sub-universe of Bob Ross fandom who had largely dropped off the face of the Earth after his father’s death—and was even rumored to have met his own demise some years earlier.

Stranger still, it wasn’t the company’s first brush with federal and other lawsuits. Although, under the leadership of the Kowalskis, Bob Ross, Inc., was usually on the delivering, rather than receiving, end of said lawsuits.

In fact, in the months immediately following Bob’s death in the summer of 1995, Annette and Walt had launched a series of lawsuits and financial claims against Bob’s estate, his widow, his half-brother, and a dermatologist in Indiana who moonlit as the writer-producer of a short-lived PBS children’s show about a talking tree in which Bob had posthumously appeared.

All in all, the strategy was designed to gain total control of Bob’s afterlife—despite Bob’s clear intent otherwise. One of Bob’s close friends took to calling the effort “Grand Theft Bob,” and for 25 years, until now, the story has been known only to a handful of people who were often too scared to speak lest they, too, be the subject of a well-financed lawsuit courtesy of Bob Ross, Inc.

The following account is based on primary documents and interviews with more than 30 people who knew Bob personally or worked alongside him in the hobby-art industry—including family members, fellow TV artists, business associates, and competitors.

PART I: MAKING BOB ROSS

To fully understand the genesis of the alleged “Grand Theft Bob,” and how it was ironically responsible for Bob’s recent meteoric pop-culture renaissance, one has to first understand the business behind Bob Ross—and the origins of the company that bears his name.

That story begins not in the sleepy pre-Disney town of Orlando, Florida, where Bob was raised. Nor does it begin in the backwaters of Muncie, Indiana, where almost all 403 episodes of his international smash-hit television show The Joy of Painting were filmed. Nor was it in the bustling suburbs of Washington, D.C., where Bob Ross, Inc., was founded and still resides.

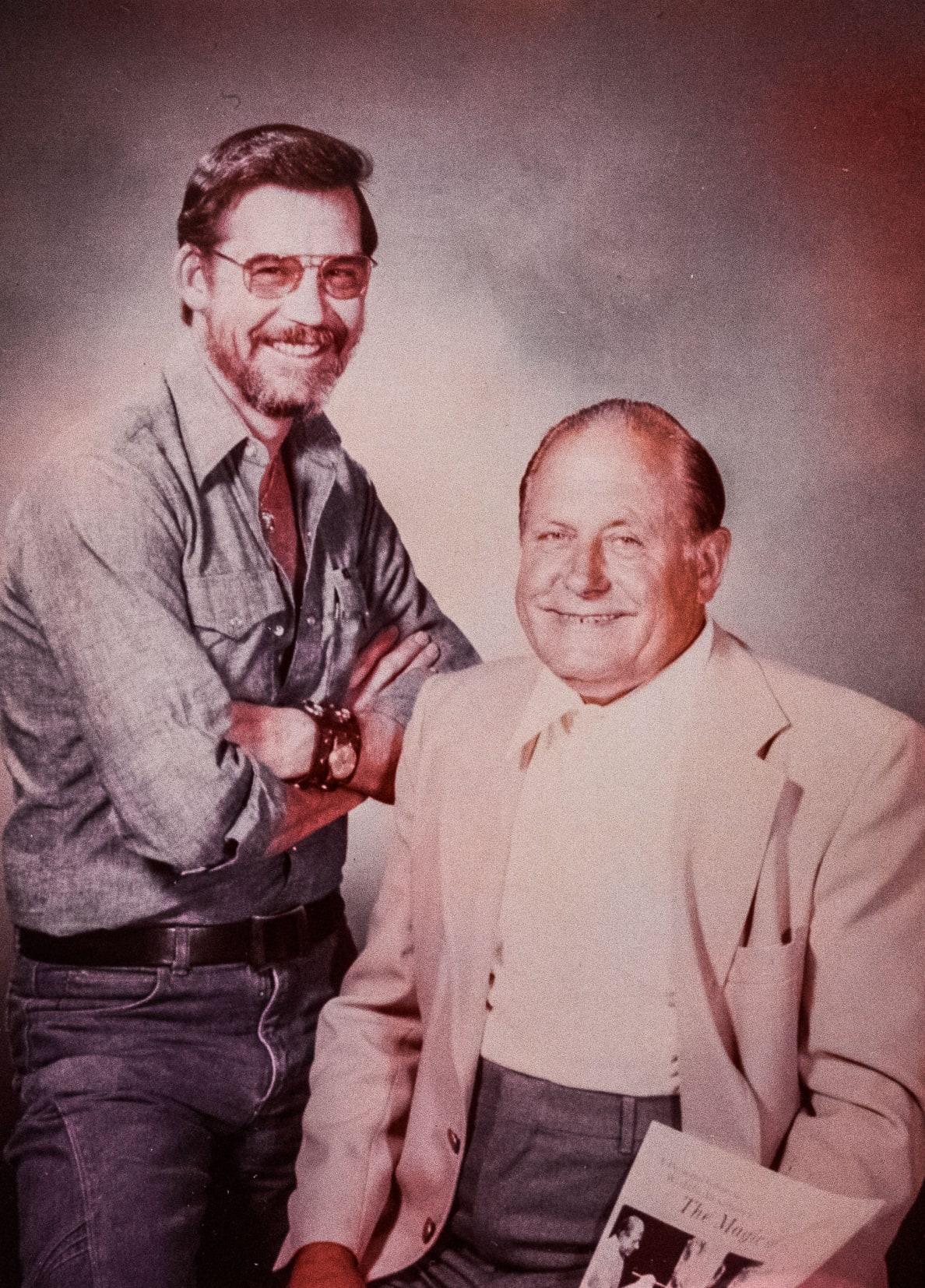

Rather, the business of being Bob Ross begins in the quaint lakeside hamlet of Coeur d’Alene, Idaho. And it starts with a chance encounter between then-U.S. Air Force Master Sergeant Robert Norman Ross and a former Nazi conscript named Wilhelm “Bill” Alexander.

The year was 1978, and, after a deployment in Thailand at the tail end of the Vietnam War, Bob had spent the last several years at Fairchild Air Force Base in Spokane, Washington, just down the road from Coeur d’Alene. Even though his days were packed with the long hours of a first sergeant—and raising his son Steve as a single father—he still found time to pursue his longstanding passion of painting. A passion that had been turbo-charged when, shortly after returning stateside, he had encountered Bill Alexander just as millions of others had at the time: on PBS, where Bill had pioneered an entirely new style of oil painting in which he could crank out a landscape in less than thirty minutes—the Alexander technique of “wet-on-wet” painting.

“It almost made me angry the first time I saw Alexander on TV,” Bob later explained in the first season of The Joy of Painting. “That he could do in a matter of minutes what took me days to do.”

Bob Ross and Bill Alexander

Handout

Luck would have it that Bill was teaching a seminar less than an hour from Bob’s post. That’s how he found himself attending his first workshop on the Alexander technique. Not only was it a chance to learn from the master himself, it was also a job opportunity. Bob was a few years shy of retirement from the military, and he knew exactly what he wanted to do next: apprentice for Bill.

On paper, the two might have seemed like an odd couple. Bob was a tall, lanky, all-American, red-blooded military man who drove fast cars, loved fast women, drank scotch on the rocks, and smoked Salem Greens and Marlboro Reds. He was laser-focused, detail-oriented, and driven to excel.

Bill, on the other hand, was a short, stocky German immigrant with a neck like a linebacker’s, fingers like sausages, and about as much energy as the sun. He was incredibly warm, gave out hugs like candy, and was often generous to a fault. His motto, in life as in painting, was that you can’t have the light without the dark.

He had already had more than his share of the dark, witnessed firsthand on the killing fields of Europe. Bill had had no desire to join the military, but the Nazi war machine mandated the service of everyone who could fight—including a carefree, wandering artist like he was at the time. He ended up serving on both the Eastern and Western Fronts, was wounded in action, and eventually found himself in an American POW camp in France. He ingratiated himself with the American officers the only way he knew how: by painting portraits of them and their family members. Those men later helped him emigrate to Canada, and from there he made his way to the United States.

Ever since the war, Bill considered every day a blessing just to be alive. Especially now that, in the late 1970s, he had found fame and a little fortune as a PBS painting celebrity so famous that the following year he’d win an Emmy for his TV show, The Magic of Oil Painting.

As much as Bob and Bill may have appeared radically different on the surface, on a more fundamental level, it’s not hard to see why they hit it off. Both had military backgrounds—and no small misgivings about that. Both were easy to laugh and quick to crack a joke, often of the ribald variety. Both were born showmen and storytellers given over to exaggeration bordering on fancy.

Perhaps most importantly, they both had an inestimable awe of Mother Nature and all of her creations—from the trees and lakes of their paintings, to the various animals that later roamed their respective homesteads.

When the workshop ended, Bob was a changed man in two critical respects. The first was that his passion for painting had turned into an obsession. Shortly thereafter, he was sent north to Eielson Air Force Base in Fairbanks, Alaska—and every last minute of his free time was consumed by art and business and the business of art. He sketched greeting cards. He donated paintings for fundraisers and visiting dignitaries. He developed an entire venture around landscape paintings on gold pans—precisely the Alaskan-themed keepsake that sold like hotcakes to tourists and locals alike.

The second, and not unrelated, change in Bob’s life was more practical: a job offer to work for Bill’s company when he got out of the military. Bill wanted more instructors to fan out across the country and spread the Gospel of Bill—as well as help sell his line of custom-made products for the Alexander technique: over-sized brushes, a palette knife of Bill’s own design, and the base “Magic White” paint that was the foundation of the Alexander technique.

When Bob hit his 20 years of active duty, he hung up his uniform and was free of Uncle Sam’s grip for the first time since he had enlisted at age 18. “I made a deal with my wife,” he later explained to the Orlando Sentinel. “I asked for one year. If I ran out of money before that, I’d get a real job and we’d act like normal people. I never went home.”

He left Steve behind with his second wife, Jane, a Defense Department civilian, and headed into the unknown.

After several months of manual labor mixing and canning paints at Bill’s headquarters in Salem, Oregon, Bob finally hit the road as one of Bill’s two traveling master apprentices to spread Bill’s technique—and sell his line of “Magic” paint products.

Life as a traveling art instructor was anything but easy. Bob was on the road north of eight months a year. He’d show up at a cheap hotel ballroom—or a church, or a civic center, or one of the countless mom-and-pop hobby-art stores that dotted the nation in the days before Michaels and Hobby Lobby. Upon arrival, he’d cover the tables, set up workstations, collect the $20-30 class fee, sell paint supplies, and then teach the actual class. At the end of the day, he’d break it all down, pack up, and move on. Rinse, repeat. Rinse, repeat.

Handout

Bob had long mastered the basics of the Alexander technique, but now it was time to master the performative element. Bill had developed a particular vernacular centered around “happy little” anything, “almighty” everything—and he exhorted his audience to “Fire in!” with a bombastic gusto that felt like encouragement by sheer brute force. Bill expected his apprentices to use the same language that had struck such a chord with his audience.

Bob honed his banter in workshop after workshop—just as Bill had done years earlier—but he did so in his far mellower voice with his own evolving laid-back style. Call it encouragement by purring self-affirmation. He billed himself as “The Happy Alaskan”—a play on Bill’s nickname “The Happy Painter,” a moniker Bob would eventually assume for himself. He embraced Bill’s “happy little” verbiage even as he dropped Bill’s aggressive “Fire In!” tagline.

For the time being, Bob was fully bought in with his role as Bill’s disciple—and keen to give Bill the credit he deserved. Bob dedicated his second how-to book to Bill in glowing terms:

In an age when it’s said that there are no heroes, I feel most fortunate to have been inspired and influenced by a giant in the field of art—Bill Alexander. He has been my mentor and friend and has been so instrumental in all that I have accomplished.

That sentiment, however, would not last much longer. And the turning point, or the start of it at least, came through a horrific turn of events—one that, in another irony, truly set Bob on his multi-decade ascent.

The event that in many ways kickstarted Bob Ross, Inc., was any parent’s worst nightmare: the loss of a child. In the summer of 1981, right as Bob was mustering out of the Air Force, that nightmare came true for Annette and Walt Kowalski, parents of five living a modest middle-class life on the outskirts of Washington, D.C.

The Kowalskis had married young and started a family in short order with five kids in only nine years. Walt worked for the Central Intelligence Agency, and those who know him said he sometimes told tales from his time in the Agency, from a gory anecdote about eating monkey brains with Vietcong, to taking a Cold War victory lap around the Kremlin on a work trip with Bob many years later. According to those same people, Walt’s defining feature—what jumped out immediately upon meeting him—were his eyes. Eyes that were cold and calculating. Shark’s eyes.

But yet, that coldness coexisted with another attribute everyone flagged: his utter devotion to his wife, and his willingness to do anything for her. That devotion came out in spades after their oldest son was killed in a car accident at the heartbreaking age of 25.

Annette fell into a depression, the sort that left her in an almost catatonic state. “All I could do was lay on the couch and watch television,” she later told FiveThirtyEight,

And that’s how she, like Bob, first became aware of Bill Alexander as he pummeled his canvas with his giant brushes and told her she could do and be anything she wanted, that the world was a happy little place full of wonder and awe. It was a ray of sunlight in the dark and tumultuous storm that had enveloped her, a glimmer of hope in an otherwise hopeless existence.

Desperate to help his wife, Walt called up Bill’s company to find a workshop she could take. Alas, there weren’t any with the master—but one of Bill’s instructors was teaching a class in Clearwater, Florida. That instructor’s name was Bob Ross, and of course neither of the Kowalskis had heard of him. No one had.

“Get up, get in the car, we’re going,” Walt ordered. Annette did as she was told, and they drove 1,000 miles south to the outskirts of Tampa to meet this so-called Bob Ross.

She showed up at the hotel at the appointed time along with a few dozen other students. Bob arrived and told them about his background, how he had trained with Bill, and what he loved about painting.

By this point, Bob had shed his military bearing and become a true man of the ’80s—with a bit of a hippy ’70s throwback vibe for good measure. He had ditched the windswept James Dean haircut that he’d carried since he was a teen and was instead sporting the frizzy man-perm about which so much ink would later be spilled. At the time, it wasn’t nearly at the literal heights it would eventually reach—and nor was it part of any clever forward-looking marketing scheme. Rather, in the early 1980s perms were in style—for men and women—and a Florida hairdresser had convinced Bob it was particularly low-maintenance.

Annette was smitten at first sight. “I was so mesmerized by Bob,” she later explained to NPR. “Somehow, he lifted me up out of that depression. I just think that Bob knew how to woo people. I said, ‘Let’s put it in a bottle and sell it.’”

Walt and Annette Kowalski

PBS

She and Walt propositioned Bob to come to D.C. and teach a few classes— and he was game for the gig. More work was more work. So they set a date for the Kowalskis’ neck of the woods and went their separate ways.

Jumping headlong into a business venture wasn’t out of the ordinary for the Kowalskis. As their daughter Joan Kowalski, now in charge of Bob Ross, Inc., explained to The Daily Beast, the two of them had always been perpetually in motion, with various side hustles to augment Walt’s government salary so they could give all of their children the chance to go to college. When opportunity knocked, they always opened the door—and here was another one.

The Kowalskis agreed to pay Bob a stipend and give him room and board at their house—and he’d teach all the classes they could arrange. Simultaneously, Walt and Annette fronted the costs to buy “Magic” painting supplies from Bill’s company, so they’d sell those as well during the classes.

Several months later, Bob showed up in Virginia, and they set off on their collective adventure. They roamed the eastern seaboard, hitting Philadelphia, Baltimore, and D.C.—and over the next year, they added Florida and Indiana to their workshop circuit. Some seminars and demonstrations went smashingly well—and others came up woefully short. There was even a class with all of one student, whom Bob dutifully taught anyway.

Despite the challenges, they finally started to gain traction as they pounded the pavement and figured out the intricacies of the hobby-art business. With their newfound knowledge, all they really needed were a few breaks to expand beyond the teaching circuit.

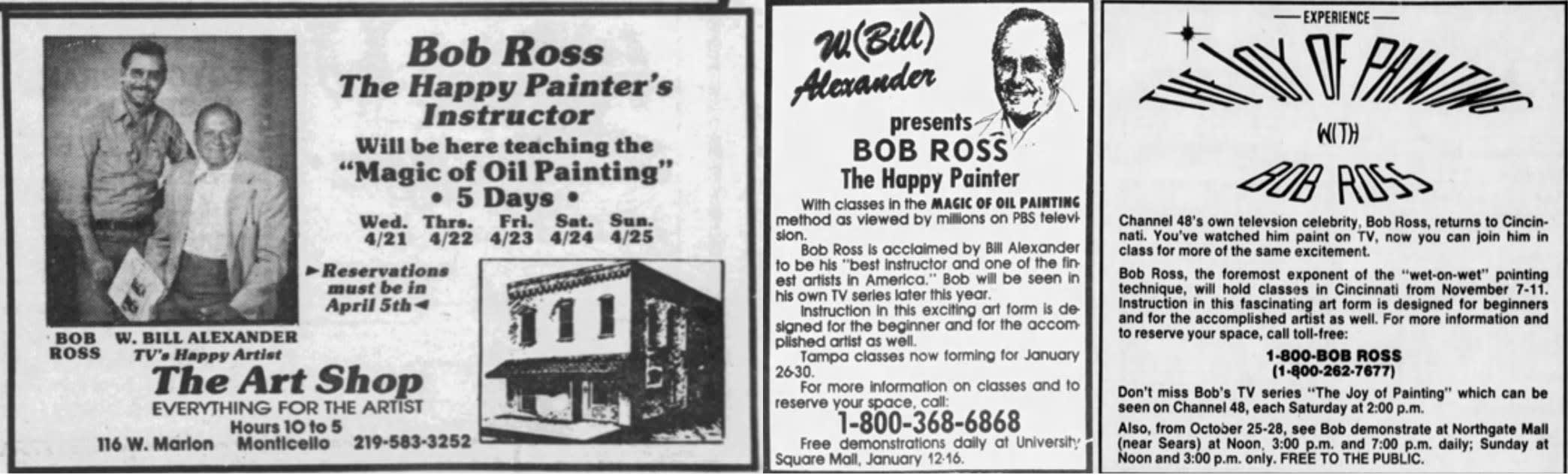

The first came largely as a result of Bill Alexander’s generosity and his willingness to help out whenever asked. This was in the form of a brief television spot the Kowalskis wanted to run to gin up interest in Bob’s classes wherever he might be. Bill and Bob recorded a promo during which Bill passed over his brush to Bob as part of their banter. “I hand over the almighty brush to an almighty man,” Bill happily crooned.

Later, this literal passing-over of the brush—as well as another commercial Bill filmed with Bob—would be made into a much larger metaphorical moment when Bill officially designated his successor. In reality, it was almost exactly the opposite: an example of the two men working together as part of the same company. Bob would get a leg up using Bill’s name to sell his services, and Bill would keep expanding his company’s reach and spreading the Alexander technique via Bob. Not to mention, they’d all sell more of the “Magic” paints that paid everyone’s bills. (Although, to be sure, at that time Bill did believe that Bob would eventually be his successor at his company when he finally put his brush away for good.)

The second break came as a result of completely random events, one of those happy little accidents that seemed to go hand in hand with Bob’s rise. In 1983, Bob and Annette were running a workshop in Muncie, Indiana, and they approached the local PBS station, WIPB, about promoting the class. Sheer luck would have it that WIPB was one of only ten PBS stations that had just received permission to run paid commercials as part of a short-lived trial to bolster PBS finances. The station was more than happy to place the Bob-Bill spot on either side of Bill’s show when it aired.

As a result of the publicity, the workshop was jam-packed—and Bob, never one to pass up an opportunity, went back to WIPB and pitched his own show, The Joy of Painting. He had tried his hand earlier that year in Virginia with an ill-fated 13-episode “series”—PBS nomenclature for a season—but the shoddy production quality had led precisely nowhere.

With WIPB’s support—and Bill’s company financing the series—Bob’s second outing with The Joy of Painting was far stronger. WIPB’s facilities might have been tiny at the time—they shot in a converted living room in a converted Victorian house—but it was far more technically advanced than the Virginia station. Gone were the production issues that plagued the first series, the canned background music Annette had insisted on, and the lack of intro and closing credits that the prior station had failed to produce as promised.

On the creative front, Bob was far better in front of the camera, and his plainspoken, down-home vibe was much more in line with the grounded sensibilities of a place like Indiana—and, it would turn out, much of the rest of the country. Once again, he gave credit where credit was due and dedicated the series to Bill and the “precious gift” he had given him.

The series was picked up by around 40 other PBS stations—a modest but successful showing. Momentum came quickly, though, as subsequent series rocketed past 100 stations and then to 200 and beyond within a few years.

As his geographic footprint expanded by leaps and bounds, Bob quickly established himself as one of the top working TV artists. He became a fixture at the PBS and art-supply conventions where the industry gathered several times a year, although Bill was still the brightest star.

For Bob, there may not have been a single moment where he pivoted from his role as an apprentice to the desire to become the master. It was more likely a slow burn as opportunities presented themselves, as doors started to creak open.

Bob may have had the soul of an artist, but he also had the mind and discipline of a master sergeant. As much as painting was a passion, it was also a profession, and the “happy buck”—as Bill always called it—had a lure all its own. Bob was under no illusions that he was making a living off of his raw artistic talent. It was the fact that he—and the Kowalskis, and Bill Alexander—were hawking paints, paintbrushes, and how-to books. They were in the art business, and a business it most certainly was.

No one knew that better than Dennis Kapp, the owner and CEO of the art-supply company Martin F. Weber. Dennis was always on the lookout for up-and-coming talent with whom he could partner, and Bob’s style and demeanor appealed to his own aesthetic preference for “happy art.” Seeing an opportunity, he approached Bob at a tradeshow and invited him to coffee—and, according to Dennis, they made a deal right then and there.

In short order, they set to the task of creating a line of Bob Ross products. It helped that they weren’t trying to reinvent the wheel. Quite the opposite, in fact. All they appeared to be doing was copying Bill’s product line almost to a tee, from their own version of Bill’s basecoat “Magic White,” to the same lineup of brushes that Bill had created over many years of trial and error, to Bill’s revered over-sized palette knife. When the Bob Ross line was eventually released, there were only minuscule differences between it and Bill’s core products.

In early 1985, the die was finally cast. Bob and Jane Ross, and Annette and Walt Kowalski, officially filed incorporation papers in Virginia for Bob Ross, Inc. All four were technically equal partners, although most knew that Bob was the decision-maker. He was the figurehead, the talent, the name, the face behind it all. Without him, the company was little more than a few pieces of worthless paper (or so it may have seemed at the time).

With the corporation live, and Martin F. Weber developing a product line, it was just a matter of time before their official launch. As 1985 progressed, Bob kept up his commitments to Bill’s company—and kept his new venture secret. The subtlest of shifts marked the new order: at the start of his seventh series in late 1985, rather than refer to Bill’s “Magic White,” Bob called it “liquid white”—his version of the same product.

A close artist friend of Bill’s, Robert Warren, recalled the exact moment when Bill found out that Bob had struck out on his own. Bill, a man of 70 long years, who had survived hell on earth and vowed to be thankful for every day thereafter—a man whose happiness buoyed all around him—that same Bill Alexander broke down and cried.

Handout

“It was horrible, it was heartbreaking,” Robert explained to The Daily Beast. “It was like he lost his son.”

“It broke his heart, and he never spoke to him again.”

Bill wasn’t the only one who felt burned by the Rosses and Kowalskis as they consolidated their control over the TV-art industry. Like Bill, some other artists in the business were more likely to view their colleagues as collaborators rather than competitors. They were dismayed by what had happened to Bill, and, later, they saw a similar playbook deployed when Annette launched a line of floral painting products that, in their view, bore an uncanny resemblance to the widely recognized masters of floral painting at the time, Gary and Kathwren Jenkins. It was as if a shark had been released among the genteel guppies of the TV art world.

Courtesy Gary & Kathwren Jenkins

“You know, it’s a business,” Joan told The Daily Beast with regard to the company’s reputation among some of the other artists. “When you start a business from scratch, you sort of decide your parameters based on the desired effect,” she added.

The sharp-elbowed parameters the founders apparently decided on, combined with Bob’s prodigious talent, allowed Bob Ross, Inc., to become the 800-pound gorilla of the hobby-art world. Even so, Bob usually floated above the fray. He had explicitly given up screaming and yelling when he retired from the military, so he was happy to let Walt handle the dirty work. In meetings over contract negotiations, for example, Bob would kindly defer to “Uncle Walt” rather than play the hammer himself if a contentious point arose.

That’s not to say Bob wasn’t a shrewd businessman. He wrote contracts and reviewed them. He was a stickler on product development, and Joan allowed that Bob could be “kind of a terror” about some aspects of the business. In her interview with NPR years later, Annette called him a “tyrant.” She caught herself and elaborated: “Do you really think this company would be as successful as it is, if he didn’t insist that everything be done a certain way?”

And successful it was. The Joy of Painting became one of the top shows on PBS nationwide. Not only did Bob become a bona fide celebrity with appearances on the Grand Ole Opry, Regis and Kathy Lee, and Donahue, among many other pop-culture moments, but the fame also hit the bottom line.

By the end of the 1980s, records made public as part of Steve’s lawsuit show that each of the four partners was making around $85,000 ($180,000 today). Several banner years in the early 1990s saw Bob take in around $120,000 ($220,000 now). All in all, the company was generating around a half-million dollars each year for the partners to divide.

Bob was by no means driven by money, as everyone who knew him strongly attests. But the newfound financial freedom did afford him the luxury to lead his life how he wanted. He returned to his roots in the Orlando area, where he pursued various hobbies that were a mishmash of his Florida heritage and his artistic achievements. He devoted untold amounts of time and money to rehabilitating injured critters. He collected Victorian opalescent glass. And he tore through the streets in his silver 1969 Corvette with its vanity “BOB ROSS” license plate, part of his lifelong love affair with hotrods.

Bob also started to dream bigger. He pondered ways to use his fame to launch new ventures, to reach new levels of stardom from which he could leave a positive impact on the world. By the early 1990s, he was working out the details of a children’s TV show he intended to call Bob’s World—which would be, as the New York Times explained it, “a wilderness version of Mr. Roger’s Neighborhood.”

He also pursued another intriguing opportunity in Branson, Missouri, a tourist mecca that was akin to the Las Vegas of the South at the time. Bob teamed up with an Indiana family that was about to break ground on a theater there, and they began developing a stage version of The Joy of Painting to accompany their Civil War musical.

Not everyone was as excited by Bob’s new ventures. Even as his fame reached new heights, the partnership that had made it all possible—the Rosses and the Kowalksis—began to crumble and then utterly collapse as it morphed into a fight for control of Bob’s name and likeness.

The downward trajectory appears to have started in 1992, when Bob’s second wife died of cancer. As a result of the company’s structure, her stock was divided equally among the surviving three partners. Thus, after her death, Bob only owned one-third of the company that bore his name—a situation that could not have sat well with a man who was used to being in charge.

There were other issues that added to the growing strains, such as Bob’s sometimes messy personal life. From his earliest days, he had issues with fidelity—like his father before him. He had fathered a child as an unmarried teen, and his first marriage had fallen apart over affairs. He was also said to have squeezes in various places over the years, as did many traveling TV artists of the time.

Regardless, the real spark that led to the final conflagration with the Kowalskis was Bob’s declining health. Although he was as tough as they come, his health had been a chronic issue—so much so that, for years, he had been convinced he’d die early. He had had a heart attack in the mid-1980s, and in early 1994, he faced his second—and final—battle with cancer.

Right after Bob learned about his lymphoma and its grim prognosis, and only a handful of days before his final Joy of Painting episode aired, he received a fax from Walt that was, for all intents and purposes, a declaration of war. It was a six-page contract, full of legalese and posturing, all with a single purpose: complete and total ownership over Bob Ross, his name, his likeness, and anything and everything he had ever touched or created—forever.

In other words, if Bob signed the contract, Bob Ross, Inc., would retroactively own much of which he had created throughout his entire life—and be able to use his name to sell any products in the future.

Walt was not suggesting he sign over all these rights for free. In exchange, he offered the whopping sum of 1 percent of revenues to him or his heirs—for the next decade.

It was an audacious ask, a brazen attempt to push Bob to do something he was likely never going to do. Needless to say, as his days dwindled, Bob did not sign that or any other similar contract with Bob Ross, Inc. According to Steve, there were, however, countless irate phone calls between Bob and Walt as they argued and fought over the company’s future—and as Bob became sicker and sicker. Steve recalls many a time when Bob would slam the phone into the receiver before emerging from another room steaming-hot mad and ranting about how the Kowalskis wanted to own his name and everything associated with it.

Again, Joan told a different version, even though she admitted she was quite young at the time and fairly junior at the company so may not have been in the loop. “I remember no tension whatsoever,” she told The Daily Beast.

As 1995 dawned, Bob’s trajectory was steadily downward. Even as he fought the advancing cancer, he set other plans in motion to thwart the Kowalskis. He made a blizzard of last-minute changes to his will, most notably inserting a clause specifically addressing his name, likeness, and the rest of his intellectual property. All of those rights were to go to Steve and one of Bob’s half-brothers.

Those weren’t the only changes to Bob’s will. Whereas the year before, Annette had been in direct line to administer his estate, now she was nowhere to be seen. Instead, Bob’s third wife, whom he married only two months before he died, came to occupy a prominent place in the estate.

The end came swiftly and slowly at the same time, as it so often does for cancer patients. Bob lost his hair—his defining feature for so many years—and rapidly shed weight. Steve returned home to help out, just as Bob had returned to Florida to take care of his mom when she was dying.

“He believed in God,” Steve explained to The Daily Beast. “But he did not believe in what God was being used for by the priests.” Steve inherited his father’s faith—a theology based outside of formal religion and all of its strictures. A faith based in the natural world and its myriad wonders.

“God is inside everything, including us,” he said. “We are part of God, and the vibration of God is within us.”

On July 4, 1995, Bob Ross felt that vibration as he became part of his God.

The funeral was small, around 25 of Bob’s closest friends and family members at Woodlawn Cemetery, a vast tract of rolling land in the suburbs west of Orlando. After paying their respects in the chapel, the funeral party made its way to the gravesite, where they entombed Bob’s gleaming aluminum coffin beside his mother and father.

The coffin may have been a Rolls Royce of burial devices, but the tombstone was anything but. It was small, flat, and generally inconspicuous. On it were a logo of Bob’s frizzy-headed smiling visage known around the world, his name, birth date, death date, and only two tiny words to sum up everything about his incredible life: “Television Artist.”

Courtesy Alston Ramsay

There was one conspicuous absence at the service that registered as odd even for those who didn’t know anything about Bob’s business, his long-standing business partners, or the enmity between them over the last year and particularly the last few months.

None of the Kowalskis attended the funeral. Not Annette, not Walt, and not Joan. They did, however, send flowers.

And in a few short months, they’d also send lawsuits.

PART II: WITH FRIENDS LIKE THESE

“Are you shitting me?”

Robert Warren was seeing red, and it wasn’t the alizarin-crimson paint on his palette. It was July 4, 1995, and as he recalled to The Daily Beast, a hotel manager interrupted his class and passed over a phone for an urgent call.

“Are you shitting me?” he repeated, as rage overtook his initial shock.

According to Robert, Dennis Kapp, the head of the paint manufacturer Martin F. Weber, was on the other end of the line—and he had just passed along the terrible news of Bob Ross’s death. But that wasn’t the real reason for the call. Dennis had a problem on his hands.

Over the past number of years, Bob Ross products had become a dominant force on his balance sheets. With Bob gone only a few hours, Dennis had a question for Robert—who was friends with both Bob and Bill Alexander as well as one of the better-known TV artists of the time. Dennis wanted to know if Robert would be willing to take over Bob’s TV show. In effect, to become the frontman for the Martin F. Weber art-supply company.

“Are you shitting me?” he said once again, far louder, as a few dozen students looked on with wide eyes.

“Bob Ross just dies, and you’re asking me to do this? I can’t even talk about this right now.”

He slammed down the phone on the receiver, his answer a clear and resounding “No.”

Dennis wasn’t the only one pondering the future of a business. With Bob’s death, the Kowalskis now owned Bob Ross, Inc., outright—but the company was at a crossroads. Its figurehead, the man on whose back the whole enterprise was built, was gone. Annette and Walt had to figure out what to do now.

Ultimately, they decided to embark on an aggressive, litigious path forward. What the Kowalskis couldn’t get from Bob while he was alive through convincing or cajoling—like the contract they had tried to get him to sign—they were now going to try to take by brute legal force. It didn’t matter if it was his estate, his heirs, or anyone with even a passing interest in Bob Ross—all were about to be put on notice that Bob Ross, Inc., played hard and played to win.

One of Bob’s close friends, John Thamm, sensationally took to calling their maximalist approach “Grand Theft Bob,” an effort to take what he and others did not believe belonged to them. (Efforts to reach Walt and Annette directly for comment were not successful, and Joan declined to arrange an interview or pass along written questions about business and personal decisions they made through the years, especially regarding their actions following Bob’s death.)

After his lymphoma returned, and as Walt and Annette’s efforts to pressure him to sign over his rights intensified, Bob had worked proactively to ensure that Bob Ross, Inc., didn’t wind up with any of his intellectual property beyond what had already been transferred to the company.

That was particularly true when it came to his name and likeness, which for obvious reasons was a bit more personal than some of the items the company clearly did own, like the copyrights to instructional art books or trademarked cartoons of Bob on paint products.

In his final few months, Bob altered his will to specifically address these issues. Most notable was the final amendment he made a mere two months before his death. That clause specified that Bob’s “name, likeness, voice, and visual, written, or otherwise recorded work” would go to his son Steve and his half-brother Jimmie Cox. And if those two so chose, the amendment also said they could “deny the exploitation of such rights” by anyone else. In a strange twist that would only come to light more than 20 years later, Steve was left unaware of the final amendment since his uncle Jimmie, the executor of the estate, had not shared the details.

“Any changes that he made in his trust he did because he felt he was doing the best thing for his family,” one of his estate attorneys emphatically told The Daily Beast. “He was absolutely competent at that time. There was no question of his ability to make changes when he did it, and his reasoning was as solid as it could be.”

That reasoning had apparently led Bob to an inescapable conclusion: he didn’t want Bob Ross, Inc., or the Kowalskis, to own anything more than the limited intellectual property around art products that he had already signed over as part of the regular course of their art business.

Although John believes Bob truly wanted his legacy to rest in the hands of his son, he also thinks there was another reason for the last-minute changes to the will: vindictiveness on Bob’s part. Revenge against the Kowalskis for what they had put him through in his final year. For what some saw as their efforts to stymie Bob’s new ventures like the children’s TV show. For their desire, above all else, to keep him forever chained to the corporate husk of Bob Ross, Inc., of which they now owned 100 percent.

The Kowalskis’ first target was Bob’s estate. When Bob died, he was worth around $1.3 million, with half of that comprised of his one-third ownership of Bob Ross, Inc. Aside from cash and stock, there were also physical properties to be divided. And then there was the matter of Bob’s actual artwork and art supplies.

Here the Kowalskis pounced. Through their lawyers, Annette and Walt demanded that Bob’s widow Lynda and the estate turn over what they considered to be their property—and they took an expansive view of what they owned. They ultimately wanted “Bob Ross’s art, all finished paintings, work copies used in the development of Bob Ross’s finished paintings, and all paints, brushes, easels, canvases, and other supplies, materials and tools used by Bob Ross.”

In other words, they contended that everything Bob had worked on was theirs, down to every last paintbrush or easel he had touched.

When the property wasn’t forthcoming, they slapped Lynda and the estate with a lawsuit demanding the items as well as damages, lost profit, and attorney fees. In some ways, Bob may have foreseen this maneuver. Upon giving a painting to one of his friends after he became sick, for example, he had written an explicit message on the back about the work’s new owner—because, according to that friend, he was worried the Kowalskis would try to repossess it upon his death.

In addition to the property they said was theirs, the Kowalskis also made claims against the estate for business and personal reimbursements. It’s a standard part of estate closures to settle outstanding debts. For instance, according to probate documents, the Mayo Clinic asked for a little more than $40,000 for Bob’s medical expenses, and Lynda asked for around $10,000 for Bob’s funeral—two standard items one expects to see.

Aside from those, the only other reimbursement claims were filed by the Kowalskis, under the auspices of costs incurred from trips Bob made to the Mayo Clinics in Rochester, Minnesota, and Jacksonville, Florida, to treat his cancer. Their expenses dated all the way back to April of 1994, 15 months before Bob died. So the Kowalskis or someone in their employ had sifted through a backlog of credit card bills from the past year and a half to come up with their figures.

There were several large expenses they wanted the estate to reimburse the company for, like Bob’s plane flights to Rochester or Annette’s trips to Florida to visit him. But there were also small expenses like $41.63 for a Travelodge in Jacksonville, $14.10 for Shoney’s, $16.92 for Cracker Barrel, $17.50 for Denny’s.

Many of the corporate expenses were charged to Bob’s company card, but quite a few were on Annette’s. So even though two of the three owners of Bob Ross, Inc., were involved in many of these transactions—and despite the fact one could argue keeping Bob Ross alive would appear to be a legitimate business expense that the company should cover—the Kowalskis apparently considered these purely personal expenses so the estate should be on the hook.

The Kowalskis’ expenses weren’t limited to just the company credit cards though. In a separate claim, they also demanded reimbursement for personal expenses—again for the trips to Rochester and Jacksonville. And once more, there were several larger expenses like hotel rooms in Rochester, along with others like $15.05 for Red Lobster, $38.10 for flowers, or $11.09 at a bookstore in Minnesota.

If none of these were business expenses, and instead Annette was there solely in her capacity as one of Bob’s close friends to support him in his time of need—well, with friends like these, who needs enemies.

There was a larger irony at play, if it can be called that. On one hand, when it came to all the paintings in the estate—Bob’s vast corpus of work—the Kowalskis argued that, since he was “work-for-hire,” whenever he put a brush on a canvas, Bob Ross, Inc., owned his time and thus all his creative work. On the other hand, when it came to Bob’s health—preserving the person whose name and likeness had made it all possible—that apparently had nothing to do with Bob Ross, Inc.

It was as if the Kowalskis had wanted to have their cake and eat it too—and if they could manage it, they apparently wanted Bob Ross to pay for the cake. Given the apparent pettiness of it all, it’s no surprise that over the years, among Bob’s friends and family, there would be rumors that the Kowalskis had asked to be reimbursed for the flowers they sent to the funeral and even tried to take control of Bob’s corpse. (There’s zero evidence for either of these.)

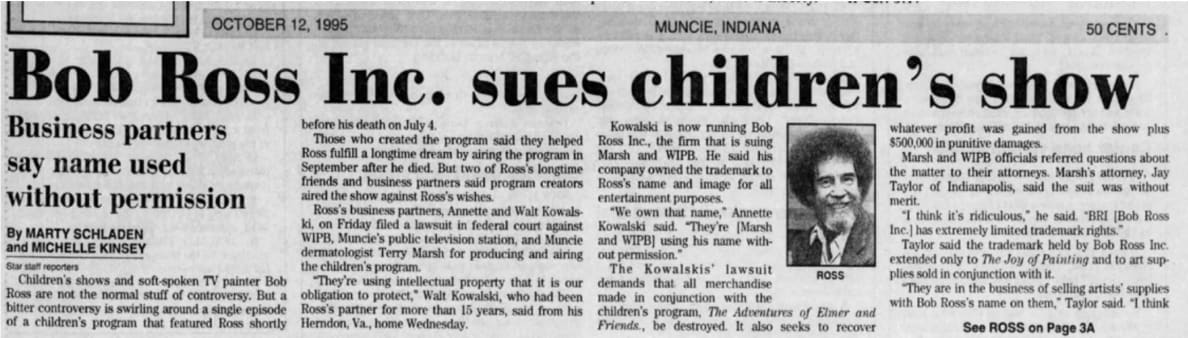

One might think that suing a dead man over items like paints and paint brushes might be scraping the bottom of the barrel. The Kowalskis could, however, go lower. Namely, suing a PBS children’s TV show for a half-million dollars as well as the very PBS station, WIPB, that had for a decade been home to The Joy of Painting.

The show in question was a four-part children’s song-and-dance series called The Adventures of Elmer & Friends. Bob had appeared as a guest star in the first episode via a green screen from Florida since he was too ill to travel at the time. He played himself, and in a handful of scenes, he helped a troop of wayward children search for a miner’s hidden treasure. The miner’s name happened to be “Old Walter,” and as Bob explained, Old Walter was long deceased.

That episode, “Treasure Beyond Measure,” aired two months after Bob died. Less than a month later, the Kowalskis filed a federal lawsuit against WIPB and the show’s producer, an Indiana dermatologist named Terry Marsh. Given Bob’s prominence in Muncie, the filing resulted in the cringe-inducing headline in one of the local papers, The Star Press: “Bob Ross Inc. sues children’s show”—accompanied by a photo of a broadly grinning Bob.

Handout

In addition to demanding the destruction of any merchandise related to The Adventures of Elmer & Friends, all profits Terry had reaped, and triple the damages Bob Ross, Inc., had allegedly incurred, the suit also tacked on $500,000 as a penalty for Terry’s allegedly “encouraging, assisting, and cooperating with Bob Ross in the breach of his fiduciary duty of loyalty to Bob Ross, Inc.”

The Kowalskis’ argument went something like this: because Bob had consented to specific limited trademark filings, such as a cartoon likeness for use on paint products, they now extrapolated that to say that Bob’s name and actual likeness—as in, his actual person, and thus what had been recorded during the show—was protected by their trademarks.

In other words, Bob Ross, Inc., owned not just Bob’s paintings but Bob himself. Or, more precisely, his ghost. “Because Bob Ross appears in that video, they are claiming that it is an infringement of their trademark,” Terry’s attorney explained to The Muncie Evening Press at the time. “We don’t see any problem.”

To no one’s surprise, the Kowalskis certainly did.

“We own that name,” Annette snapped to The Star Press. “They’re using his name without permission.” Through the media, she also threatened to yank WIPB as the presenting station for The Joy of Painting—a threat she would ultimately make good on. She piled on, saying that “Bob’s last words to me were that he was very, very upset over what Terry had done, and he refused to pay him” for his share of the production.

Annette may have omitted a couple of important details. First, according to Terry, it had been Bob’s idea to reimagine the episode in question so that Bob could, even in his poor health, participate in the filming from afar (the main shoot was at WIPB). And second, given what Bob was going through, Terry says he had simply paid the tab himself since he didn’t want to bother Bob about money while the man was fighting for his life.

Of course, there was another critical element Annette omitted. And certainly one that she and Walt likely didn’t mention when their lawyers castigated Bob for his lack of “loyalty” to Bob Ross, Inc.

It fell in the category of inconvenient truth—and for their lawsuit, extremely inconvenient truth. The lawsuit had explicitly said that “Bob Ross, Inc., did not consent to Bob Ross’ and to the defendants’ production of a video cassette recording of or other use of the name and likeness of Bob Ross.” Yet in reality, Annette or Walt had explicitly given permission to Bob to film the show. And there was an actual tape recording of the conversation.

via The Adventures of Elmer

It turns out that, in his last months, as the chemotherapy and radiation took a toll on his memory, Bob had been in the habit of recording his phone calls. Which included one in which Annette or Walt gave him permission to do the show. This only came to light when Terry was on the phone commiserating with Lynda. She knew Bob had been told he could do the show, and she provided the tape recording that proved it.

The Kowalskis’ entire case was built on a lie so egregious that Terry’s lawyer thought he had a slam-dunk case to go after the Kowalskis for filing a blatantly frivolous lawsuit. Terry didn’t want anything to do with it though. He just wanted to be done with the Kowalskis. In short order, he and WIPB settled the matter.

Terry had the last word on the whole sordid affair, which he broadcast through The Muncie Evening Press: “It was the last work [Bob] did in his life and the fulfillment of a lifelong dream [to host a children’s TV program]. He was very proud of the show and would have been heartbroken had he known his partners had sued to have it destroyed.”

When the settlement went public, a clever headline writer at The Star Press couldn’t resist the perfect Bob Ross pun: “Taped conversation paints new picture.” The story led with the old saying that “nobody ruins a good story like a witness.”

The Kowalskis were not going to make the same mistake again. In April 1997, almost two years after Bob died, Jimmie signed an agreement on behalf of Bob’s estate to settle the Kowalskis’ lawsuit. The destruction of the audiotapes was one of the key clauses.

In the final analysis, the Kowalskis’ approach proved to be a winning strategy. Few could or would go toe to toe with well-heeled, and well-financed, lawyers whose clients had made it clear that there were not many levels to which they would not stoop.

With the lawsuits settled, Bob Ross, Inc., was in the free and clear to roll on through the rest of the 1990s. The initial concern that The Joy of Painting might fade from the airwaves was quickly put to rest. With 403 episodes on tap, it really didn’t seem to matter to Bob’s fans, or PBS station managers, whether he was alive or dead. On TV at least, he had achieved one of his explicit goals in life: to become immortal.

Finally, in 2012, as Annette and Walt reached their seventies and eighties, respectively, they turned over the reins to Joan—and a new era began for the business.

Joan explained to The Daily Beast that her expansion into Bob Ross licensing beyond paint products was little more than a happy little accident. Much as her parents had kept their nose to the grindstone of the paint business while Bob was out there creating a show he presciently hoped would last forever, Joan likewise was so close to the paint business that she didn’t see the potential for other revenue streams centered on Bob.

That is, until a licensing company named Janson Media approached her with an offer. The social-media platform Twitch was starting a new online channel, and they wanted to launch it with a Bob Ross marathon. Joan was leery—as she and her parents had always been about streaming since they felt like they’d lose control of The Joy of Painting, the crown jewel of the company’s intellectual property. But one of her nephews understood the potential. “Aunt Joan, you want to do this,” he told her in a Facebook message.

“It would be a lot of money, which we needed at that point,” Joan said.

She said yes to the proposal, and in short order the Twitch marathon launched Bob Ross into a new stratosphere. “Twitch.TV woke up the world,” Joan told the online journal Vocativ in 2015, around the time of the marathon. “They made everybody remember their childhood again even though we’ve always been here…We are freakin’ out.”

Years later, she’s more reflective about the rocket ship Twitch launched back then. “Yes, we were surprised but not really,” Joan explained to The Daily Beast. “Finally, finally, we’re doing what Bob wanted” and truly spreading his message to the masses at the scale about which he dreamed.

The Bob Ross renaissance opened up a whole new world of money-making opportunities. Janson and a separate brand-management company named Firefly super-charged the Bob Ross branding business—and the money started rolling in.

Based on court documents turned over as part of Steve’s lawsuit, in 2012, when Joan took over, Bob Ross, Inc., brought in less than $200 in licensing revenue outside of its paint products. In 2015, that number was still only about $40,000, but the following year it rocketed to $460,000. And the year after that, 2017, Bob Ross-branded products were kicking off well north of a million dollars in licensing fees to Bob Ross, Inc., in almost pure profit. It’s a safe bet that number has only climbed in the ensuing years, especially now with national corporate campaigns like the Mountain Dew commercial.

Walt Kowalski

Courtesy Bert Effing

There was only one small issue. As had always been the case, it wasn’t entirely clear if Bob Ross, Inc., owned what they were selling since the Kowalskis’ lawsuit against and settlements with Bob’s estate left some of Bob’s intellectual property—especially the right to use his name and likeness for commercial products—in a potential legal gray zone. If this were in fact the case, the only way to unmask it would be in a court of law. And it would take motivated litigants to go head-to-head with Bob Ross, Inc.

The events that led to Steve Ross’s faceoff with Joan and Bob Ross, Inc., started with the third family that had made Bob Ross all that he was: the Kapps, whose patriarch Dennis had played a critical role in marketing Bob Ross’s paints for more than three decades. Several years ago, Joan decided to leave Dennis’s company. “We saw some things in that organization that concerned us,” she explained, clearly biting her tongue in order not to sling mud. “It was a shrewd and necessary business decision.”

It also immediately blew a hole in Dennis’s balance sheet so big the company was suddenly at mortal risk. It fell to Dennis’s son Lawrence, a garrulous businessman, to try to save the family enterprise.

Lawrence’s idea was to engage a new frontman for a new line of paints—someone who would have instant name recognition, if not at Bob’s level then at least close enough to keep the company afloat. And the person who immediately came to mind was none other than Bob’s son Steve.

Lawrence reached out to see if Steve might be interested, but Steve immediately flagged a problem: the possibility of a lawsuit by Bob Ross, Inc.

For decades, Steve had heard the company’s footsteps behind him. His abiding worry was getting sued over his own surname. As Steve recalled to The Daily Beast, he always remembered a phone call he received back in 1995:

Annette called me two days after my dad died, and she said, “I want you to listen to me carefully… Any Bob Ross art products, anything related to art or painting… you can never ever make those, distribute those, create a business around those—nothing. But if you would like you can do anything not painting- or art-related that you want. You can do Bob Ross pickles, Bob Ross shoes, Bob Ross whatever. But you cannot put the Ross name on a painting- or art-related product, period—ever—for the rest of your life.”

None of this had ever really come up though since, prior to Joan’s taking over, Bob Ross, Inc., had never expanded beyond the core paint products. “Walt and Annette knew what would happen if they did do it,” Steve said. “Joan was stupid enough to do it, and that’s what triggered me” to pursue a lawsuit.

Steve Ross and Dana Jester

Courtesy Steve Ross

Steve had another trigger too. For the first time, he learned about the final amendment to his father’s will—the one that theoretically turned over the intellectual property to him. He suddenly realized he had a strong legal claim to his father’s legacy.

Steve and Lawrence joined forces with one of Bob’s best friends, Dana Jester, and formed an LLC. They retained an intellectual property lawyer to press their case for the ownership rights to Bob’s name and likeness as well as damages for alleged infringement as a result of Bob Ross, Inc.’s foray into the broader licensing business. The trio even went ahead and filed a trademark to use a sketch of Bob’s face on rolling papers and other weed- and tobacco-related products.

Joan was somewhat shell-shocked when their lawyer reached out. “We hadn’t heard from Steve for 25 or so years,” she said, and then the lawyer’s letter arrived. “We didn’t have an opportunity to have any sort of a conversation, but we would have liked that,” she added.

Rebuffed by their request to discuss a settlement, in the summer of 2018 Steve and his partners filed a federal lawsuit and headed to court. In many respects, the case was a blast from the past—a redux of the earlier 1995 lawsuits against Bob’s estate about “work for hire,” oral contracts, trademarks, and copyrights.

After a year of claims and counterclaims—and depositions about odorless thinner, brush beater racks, bungee-cord easels, and other items one imagines made their first-ever appearances in federal court—the lawyers had finally made their cases. That fall, almost a quarter-century after Bob’s death, a judge in Virginia set to the task of determining where the world’s most famous TV artist should reside in perpetuity.

Six months later, he rendered his decision. In his view, Bob had in fact given all of his intellectual property to Bob Ross, Inc., during his lifetime via oral contracts that would have been confirmed by written contracts, if the written contracts had existed. No matter, apparently, that the written contracts did not exist. Thus, the final amendment to the will was irrelevant since the intellectual property in question was, by that time, not Bob’s to give to anyone else. In other words, Bob Ross, Inc., owned it all.

Steve and his partners thought they had a strong case on appeal, but they didn’t have the cash to continue the fight—nor did they want to be tied up in legal limbo for the foreseeable future. From the onset, what they had really wanted was the right to use Steve’s name—and the assurance that they wouldn’t be hit with a well-financed lawsuit from Bob Ross, Inc., if they did.

In the end, they struck the best deal possible under the circumstances. In exchange for a modest payment, Steve gave up his claims on Bob’s intellectual property. Most importantly for him, perhaps, Bob Ross, Inc., gave him the clearance to move forward with his business using his name and the right, under non-disclosure agreements, to show some terms of settlement to prospective business partners who might be fearful of a Bob Ross, Inc., lawsuit if they were to get into bed with Steve.

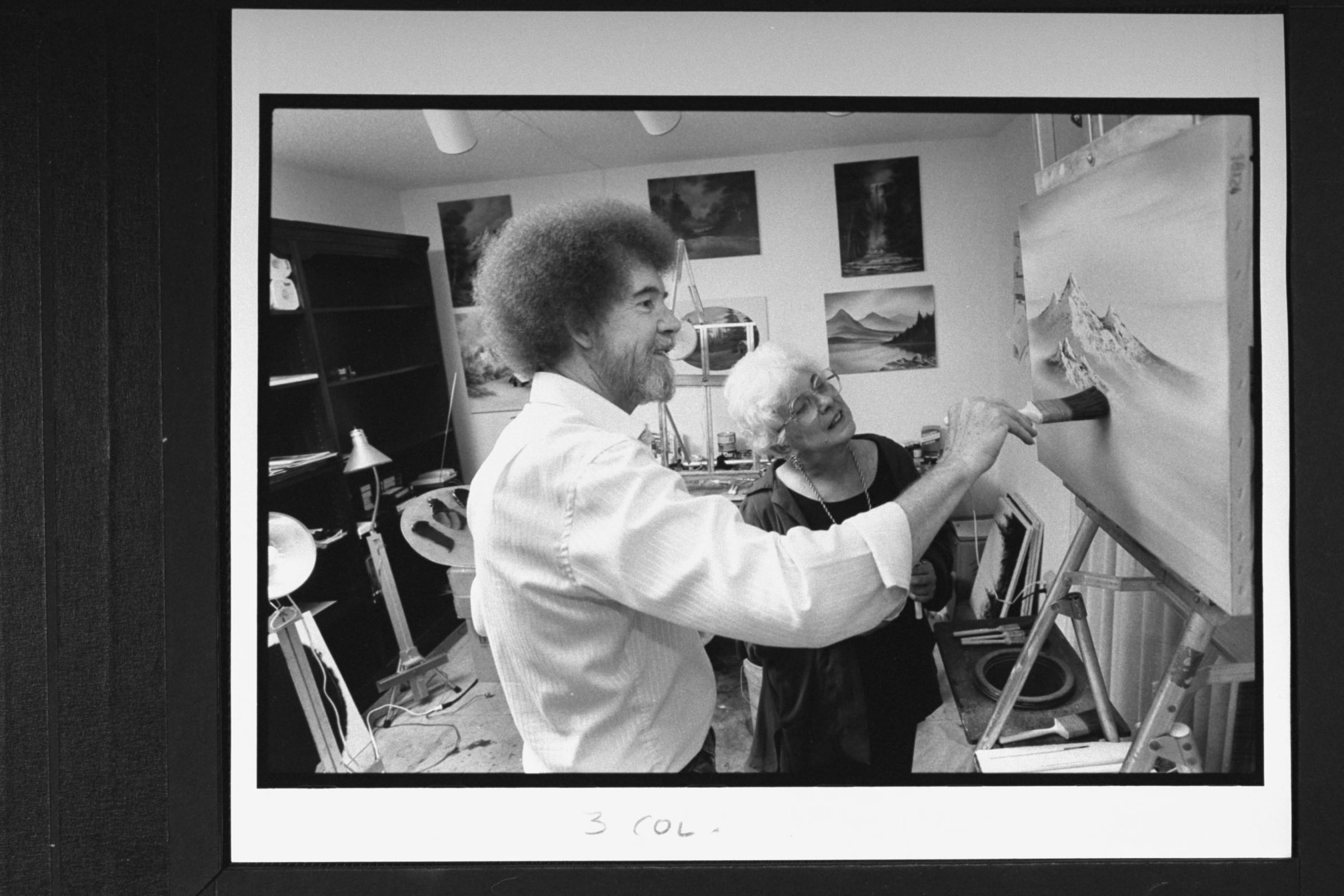

Bob Ross at easel painting one of his mountain landscapes as his business partner Annette Kowalski looks on in his studio at home.

Acey Harper/Getty

All and all, it was a bitter pill for Steve and his partners. Barring a miracle, the Kowalski family’s company will own Bob Ross’s name and likeness, and financially benefit from his good name, for as long as there’s money to be made off of it.

Of course, it’s also impossible to escape the cold, hard reality that had the Kowalskis folded shop back in 1995 after Bob passed, it’s highly likely that Bob would have faded into obscurity much as Bill Alexander has. There simply wasn’t anyone else in Bob’s orbit with the right skill set or business acumen to navigate the intervening decades, whether that was Walt and Annette’s keeping Bob on the air in the U.S. while expanding internationally, or Joan’s bold venture into the realm of brand licensing to create a new roadmap for the internet age.

“I know that I’m doing exactly—exactly—what was intended by Jane, Bob, Walt, and Annette,” Joan told The Daily Beast.

Steve may have lost one aspect of his father’s legacy for good with the stroke of the judge’s pen, but he did gain something as well. Something for which there is no monetary value. Something that had been missing from his life ever since his dad had passed into the great unknown.

That something began a little before 9 a.m. on Wednesday, Sept. 24, 2019, an hour due east of the tiny makeshift TV studio where Bob Ross had launched his career all those years ago. Nestled between endless cornfields, and a few towering windmills that slowly spin in the breeze, the 4-H Fairground in Winchester, Indiana, is little more than a squat, faded white building with a sun-baked gravel parking lot. Despite the inglorious setting, on this day, at this hour, the 4-H is about to become the temporary center of the Bob Ross universe.

Several dozen artists have converged here for a painting workshop unlike any other in recent memory. For the first time in at least 15 years, it’s an opportunity to learn from Bob’s two most trusted master painters: Steve and Dana, Bob’s son and his best friend. At this point in history, aside from Annette, they spent more time than anyone else in direct contact with the man for whom they are his most devoted disciples.

For those gathered, it is a workshop with two living legends. At nine sharp, with little fanfare, Dana takes the dais at the front of the 4-H’s cavernous single room, gives a brief introduction, and demonstrates the first step of today’s painting—“Sunlight in the Shadows,” the same crimson-hued forest scene he painted when he guest-hosted an episode of The Joy of Painting back in 1993. He even uses one of Bob’s old easels, and later on he’ll show off other memorabilia like the “BOB ROSS” vanity plate that graced Bob’s corvette.

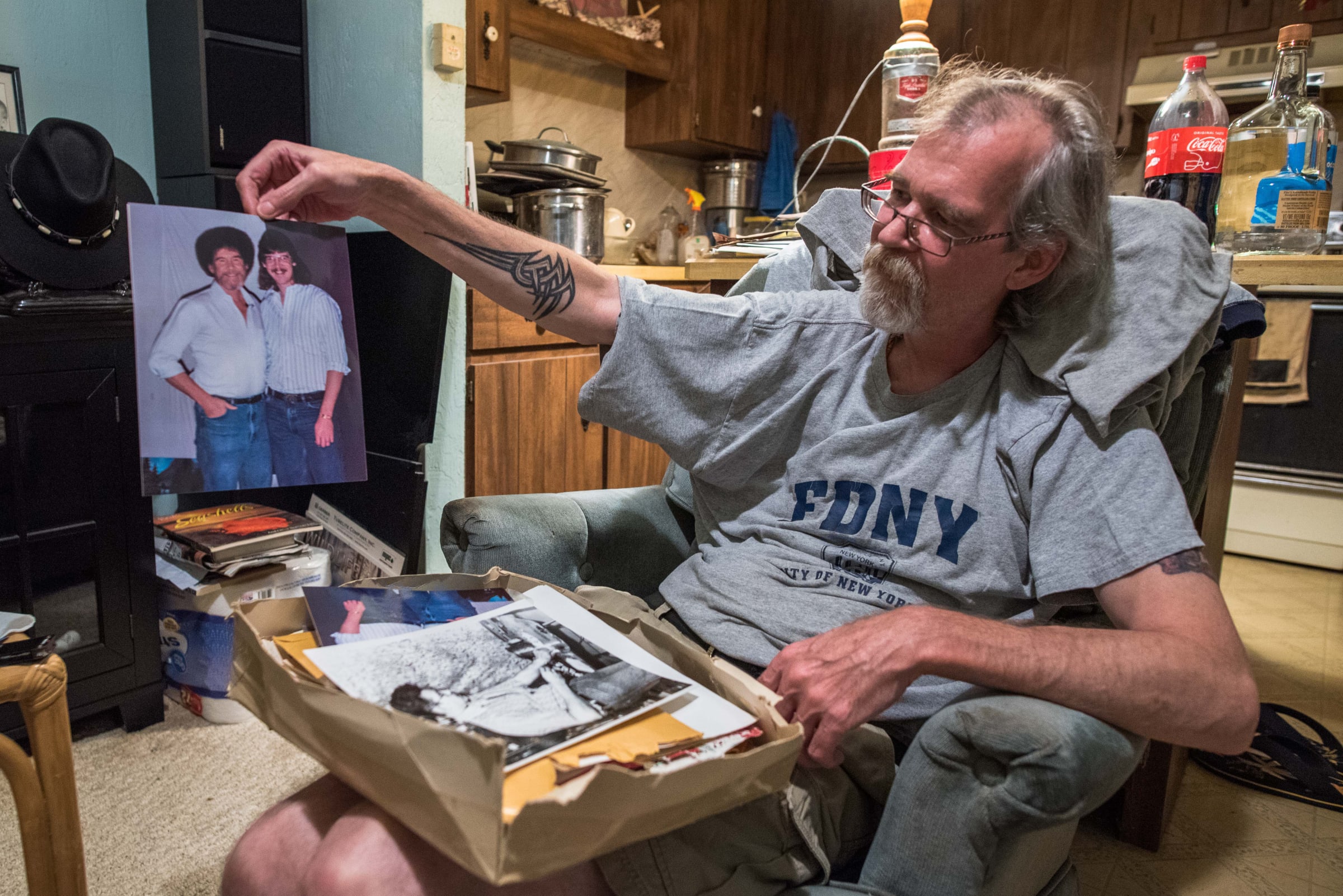

Steve Ross admiring a picture of his father

Courtesy Alston Ramsay

Dana is certainly a draw, but for most, Steve is the star of the show. And on Thursday, when it’s Steve’s turn to teach, he is as he will be throughout the four days of painting and socializing over pizza and beer: talkative, funny, empathetic, and with such brimming artistic talent that it’s almost like he’s performing a magic show whenever he puts his brush on the canvas. In fact, Bob’s closest friends all say Steve is a better painter than his father.

Steve is such a natural in front of the crowd that it’s almost impossible to believe that this is the first time he’s taught in a decade and a half—or how long and hard his journey has been to reach this point.. Back in 1995, in his final words to him, Bob encouraged Steve to always “continue”—a simple but prophetic acknowledgment that he knew how much Steve might struggle in his absence.

And indeed, Bob’s death had dragged Steve into a dark depression from which he almost didn’t escape. At one point shortly after Bob passed, Steve was driving on a highway when suddenly an impulse washed over him to swing his car into oncoming traffic to end the pain once and for all. He gripped the wheel tight and managed to keep it together—but just barely.

The depression also affected his livelihood. He had been painting since he was a child, but after his father’s death, that which had given him so much joy and self-worth became inextricably tied to the worst moment in his life. He did paint and teach some over the ensuing years to make ends meet, but he eventually dropped off the circuit entirely and settled into the hermit lifestyle that would define his existence for the next 15 years.

That is, until the legal confrontation with Bob Ross, Inc., rekindled his fire and brought him to Winchester for the workshop with Dana.

All in all, the seminar was a smashing success: four days of painting six to eight hours a day, Bob Ross bon mots galore, and a group of likeminded devotees bonding over their shared love of painting as Steve and Dana regaled them with never-ending stories about Bob.

When Steve returned home to Florida, he hopped online to see if any of the attendees had said anything about the event. He wasn’t expecting much, but what he found was a show-stopper. There were words of love and words of kindness. The same sort he had doled out to the painters—but directed at him.

“I didn’t realize that people missed me or wanted to have me do this again,” he said. “I always knew, but what I mean is, maybe I didn’t want to know. Maybe I reserved the right to remain ignorant.”

On and on Steve read. About all the people who had come to learn from him. About how he had touched their lives in profound, meaningful ways—just as his father had. As the words of kindness flashed across the screen, as he took stock of it all, suddenly a deep emotion welled up inside and barreled toward him like a freight train.

And then it hit him. Steve took a deep breath, and he began crying. Tears streamed down his face as he felt the long-absent grace of God in that simplest of emotions, the one that had been absent in his life for so long that he had forgotten what it even was.

Joy.

“Like the first time I’ve had the sun on my face in a thousand years.”

Alston Ramsay is a writer and producer in Los Angeles. If you have any information related to this article, please e-mail him at BobRossTips (at) gmail.com