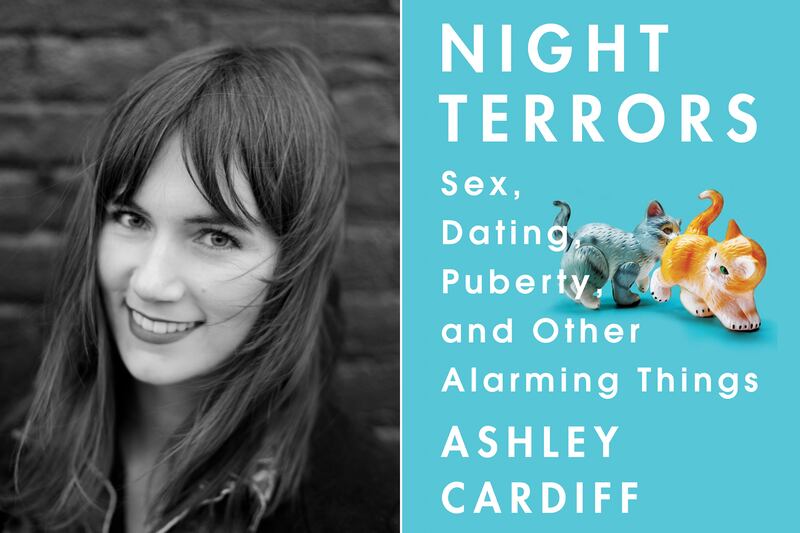

These 23 essays arrive in paperback with a slew of metadata—cover, blurb, press release—that either e- or in-vokes short-form forerunners Aimee Bender, Sloane Crosley, and David Sedaris. Against this test it holds up pretty well: Cardiff is a professional blogger on the lady beat, so she’s had years of writing, writing that slips down easy—and at first blush these are deft and funny and sugary, often deliciously bitchy, and many short enough to wolf down in the bathroom during a slow dinner party. Good fun. I LOL’d.

The problem is that it isn’t really that sort of book. It looks like it and reads like it—the rhythms are all flippant callbacks, withering cuts, and essay-ending buttons that play like piano tinkles—“Can you imagine what kind of hero you’d have to be to look noble while jerking off? I’d guess a fireman.” But the mask of facility slips from time to time, as this manifestly learned writer (gerunds, Lucretius) prances gaily for the cheap seats, treating heavy moments to a cavalcade of vagina gags and stooping to others still lower: Aerosmith, abortion, Zunes, MIDIs, rape, toddler dance recitals, all get drive-by zinged. This starts out delightful, then begins to feel minstrelish, then somehow gets tuned out, like Woody Allen compulsively cracking wise to an audience of one. No doubt this is clear policy, agreed at the highest levels at Penguin, her publisher, to keep the sugar-to-medicine ratio high. And if there’s a lot of sugar in here (there is; it’s funny), it’s because there’s also a staggering amount of medicine.

*

Recapitulation Theory is the idea that the development of the embryo in uterus “recapitulates” the evolution of the species. There’s a similar geometry to these essays, which are styled to echo the author’s own sexual development: we start out with a carefree and primary-colored little melody; then complex chords creep in, nothing serious, still very hummable; and then we’re under a Beethoven shame fugue with panic attacks and full-spectrum revulsion, where we stay for most of the book, boiling with Holden Caulfield fury not just about sexuality and its discontents, but about gender, family, jobs, hell, people—

“normal, shitty people, the kind you see everywhere, clogging streets and subways with their sagging guts and coughs and half-formed ideas and nonexistent attention spans and their fucking hats.”

It’s a primal scream transposed into repartee. Only in the last few pages does it all simmer down into something like an adult’s uneasy truce with the world; it does feel like you just went through puberty again. It’s a testament to Cardiff’s humor that she—mostly—keeps you gulping this bitter philter, in the above, for example, with the “fucking hats” punchline, which is a reference to absolutely nothing at all and which is therefore hilarious.

But there are legitimate targets for rage. Her Mormon boyfriend, stricken with guilt, takes her to meet his bishop, where they jointly receive holy contempt. Another boyfriend’s mother tells her about his other, better girlfriends. Another boyfriend jerks off to the rape scene in Irreversible. Cardiff wants you to know that she’s put up with this bullshit for 20-something years, but now that she’s got a book deal she’s meting out some comeuppance. She metes it with a flamethrower. She lights up everyone that ever belittled her or made her feel the “shame and disappointment at being a girl,” including—especially—herself. For herself, and indeed for this very book-length exercise in esprit de l’escalier, she reserves a special scorn. This passage ends a diatribe about a woman who pooh-poohed her decision to study classics at university:

“It is monstrous, though, to ridicule teenagers who care about their education, while the absolute most monstrous thing is to lack the courage to speak up for oneself in moments of minor conflict and then, having stewed for years, write a vicious takedown of everyone who ever wronged you, especially that woman who wore rainbow-striped socks with the toes in them. Well, fuck her.”

Partly, knowing the criticism her stridency will provoke, Cardiff is just beating you to the punch; partly it’s fourth-wall joke; and partly it’s the I’m-so-awkward-and-useless gestures that are more or less priced in to the genre at this point (of which there are a lot). But Cardiff takes it further. When a man drunkenly confesses the failure of his life to her—he got a girl a pregnant, she had an abortion, he dropped out of college—Cardiff mocks him. She tells it unflinchingly. My hands shook to read it. In this moment she is a macabre and terrible person, as wholly deserving of her own condemnation as everyone around her. It is not comfortable. The reviewers on Goodreads hated it. It’s exhilarating.

So what emerges is something of a feminist jeremiad, dressed to sell. Not that Cardiff uses the F word, except as a punchline: there’s no identities of womanhood, alienated states, cis norms, or patriarchies here, which will no doubt lead some to regard it as lacking heft—to my mind it takes a real writer to dodge abstractions. That this book provokes genuine indignation against all the agents, male and female, internal and ex-, that have conspired to enforce the passivity and gender roles (“incubators you can fuck”) deemed appropriate for our precocious sass-mouth narrator, strikes me as the highest aim for feminist writing. But, typically, Cardiff can’t stop there; and in the closing pages opens up on her own side: she didn’t major in women’s studies at college because “I figure if you’re going to go into suffocating debt for a college education, you might as well learn something.” Scorched-earth policy, here.

*

Some inside baseball: the New York media scene is tremendously interconnected, its members obsessed with their Twitter scores and falling over themselves to correct each other with a slightly more nuanced point than the next person—and where America’s most flamboyantly extroverted come for attention. Writing about themselves having sex is a time-honored way for young women to get it. Chelsea Handler, Lena Dunham, Cat Marnell—well, you get the picture. The list is long.

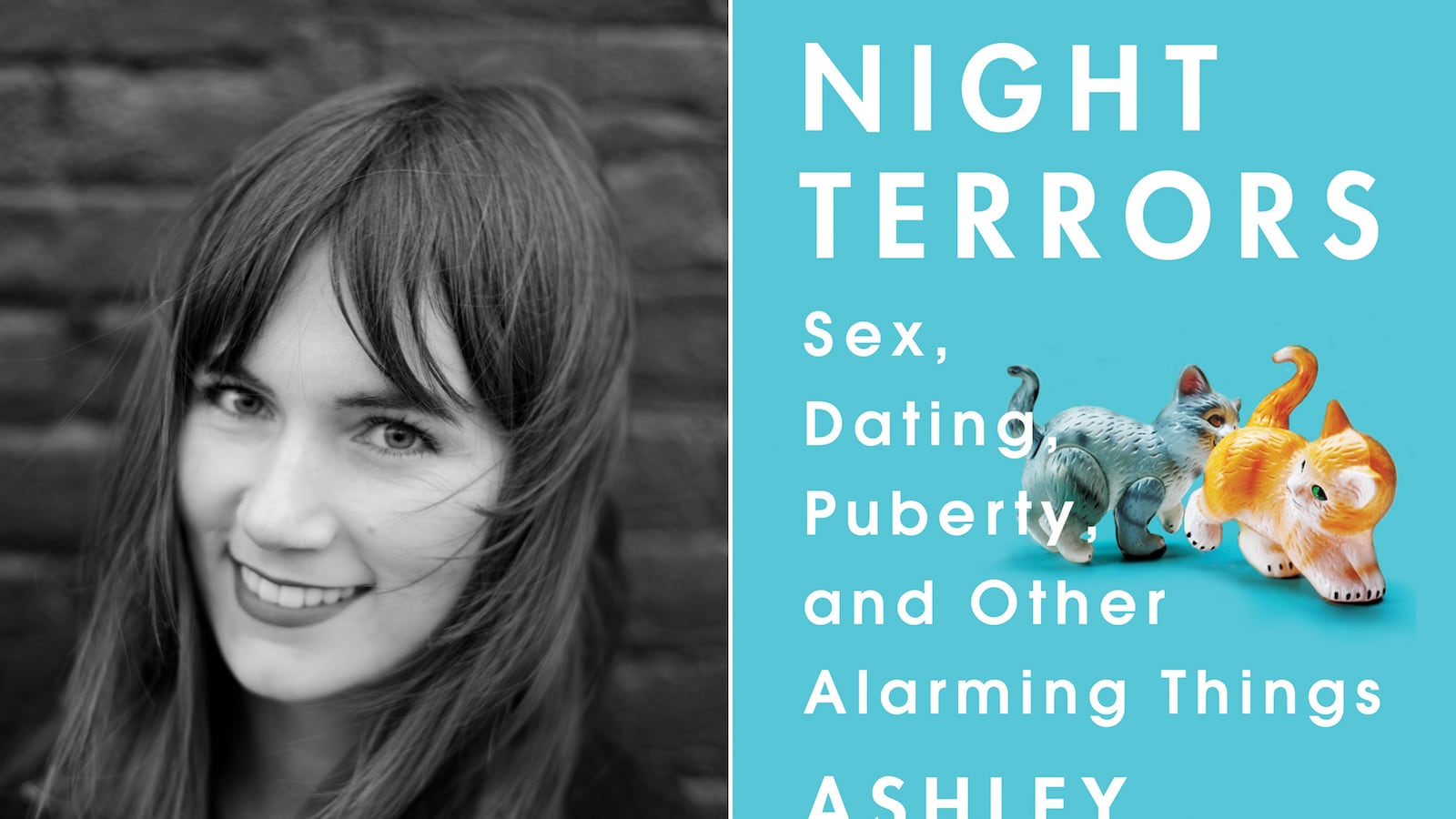

The introverted can do this too, but more cautiously. One could make a Meyers-Briggs diagnosis just from Cardiff’s tweet count; and having met her around town, I can confirm she’s no exhibitionist. In fact this book feel titrated through a mountain’s worth of limestone and angst before dripping painfully out. And for what it’s worth, it doesn’t even read like she particularly wanted to write this book. She mentions several times how becoming a writer was her lodestar during her teenage years; she dropped out of grade school in order to further this goal; it kept her company while she endured all the creeps, fumblers, pickup artists, strippers, cat-ass-mouthed matriarchs, orgiasts, and statutory rapists that populate this book. She has burned not with a specific message, but with the desire to be a writer, which is a different thing. She fought her way into New York, then into the writing business, and now finally her wish has come true. But hers was a mischievous genie, who added the caveat: it has to be about your love life.

Well, you don’t get the cushy jobs first. But it seems she took a deep breath and signed on the dotted line and served up her most literally private parts as entertainment: sexual function, masturbation habits, what let’s call her pubicity, relationship postmortems, all here with what have no doubt been percussive consequences in her private life. Even though there’s no actual sex scenes, nothing glistening or squelching or going in (“that shit is cheap like casual swears”), I wince at how much whiskey she must have knocked back in order to strip down the way she has. It’s an embarrassing, and therefore impressive, debut, of a writer looking her subject in the eye and not blinking. That the topic was sex seems practically incidental. And in contrast to other confessional sex writing, Cardiff doesn’t feel like a shot bolt; her caustic voice, density of cognition, and tireless gag reflex (sorry) make it seem like she’s got plenty more where this came from—and which will no doubt again be sold as sugar.