What makes a movie like Chinatown break a heart? What desperation did Sam Wasson try to touch, as he wrote The Big Goodbye, about Chinatown’s creation during the long-gone ’70s filmmaking era?

Roman Polanski gave Wasson the answer: talking about watching Of Mice and Men as a teenage boy and leaving a Warsaw theater with Lenny’s death in the forefront of his mind. Wasson wrote, “it was unlikely Polanski would still be thinking about the ending… if it hadn’t hurt as it had.

“What made him remember, years later, the film with love, was the tragedy.”

The power of pain and failure had a disciple in Chinatown’s screenwriter Robert Towne. Early in the absorbing and gossipy The Big Goodbye, Wasson captures Towne’s creation of the narrative arc of his private detective Jake Gittes, who “would only think he knew the world.”

Towne knew that, “By the end of the story, Gittes would capitulate to a new and terrible awareness of corruption… all his venality, his air of self-possession would come crashing down.”

To create Gittes, Towne channeled the most extreme aspects of his close friend Jack Nicholson’s self-admiring personality, writing the part with Nicholson always in mind. Gittes became a glib, cocky “popinjay” who, as Wasson puts it, “would mind his hair, his fresh-pressed suits, his Venetian blinds. He would be class-conscious, maybe a little Hollywood… Towne’s hero would do it for the money.”

And then, “The detective would lose the case, the woman, himself. He would lose, Towne came to realize, everything.”

Wasson’s motivation to explore Chinatown, the noir classic of corruption’s triumph, came from our era’s “Chinatown-ization of Hollywood and America—my own Chinatown-ization of loss and futility,” Wasson told The Daily Beast.

“What’s the precedent for this emotional component in the movies? The cinematic myth… for this corrupt force?” he said. Just as Polanski saw the enduring memory of tragedy and betrayal from Of Mice and Men, Wasson saw in Chinatown an answer for his own question. “If I was Greek, it would have led me to Greek tragedy. I write about film, so it led me to Chinatown.”

The Big Goodbye recreates the early-’70s partnership of Towne, director Polanski, Nicholson, and producer Robert Evans, creative talents at their most towering, visionary, flawed, far-reaching and often petty. The book works as eulogy or valediction. Both words mean the same thing; it’s a choice of how to see a life.

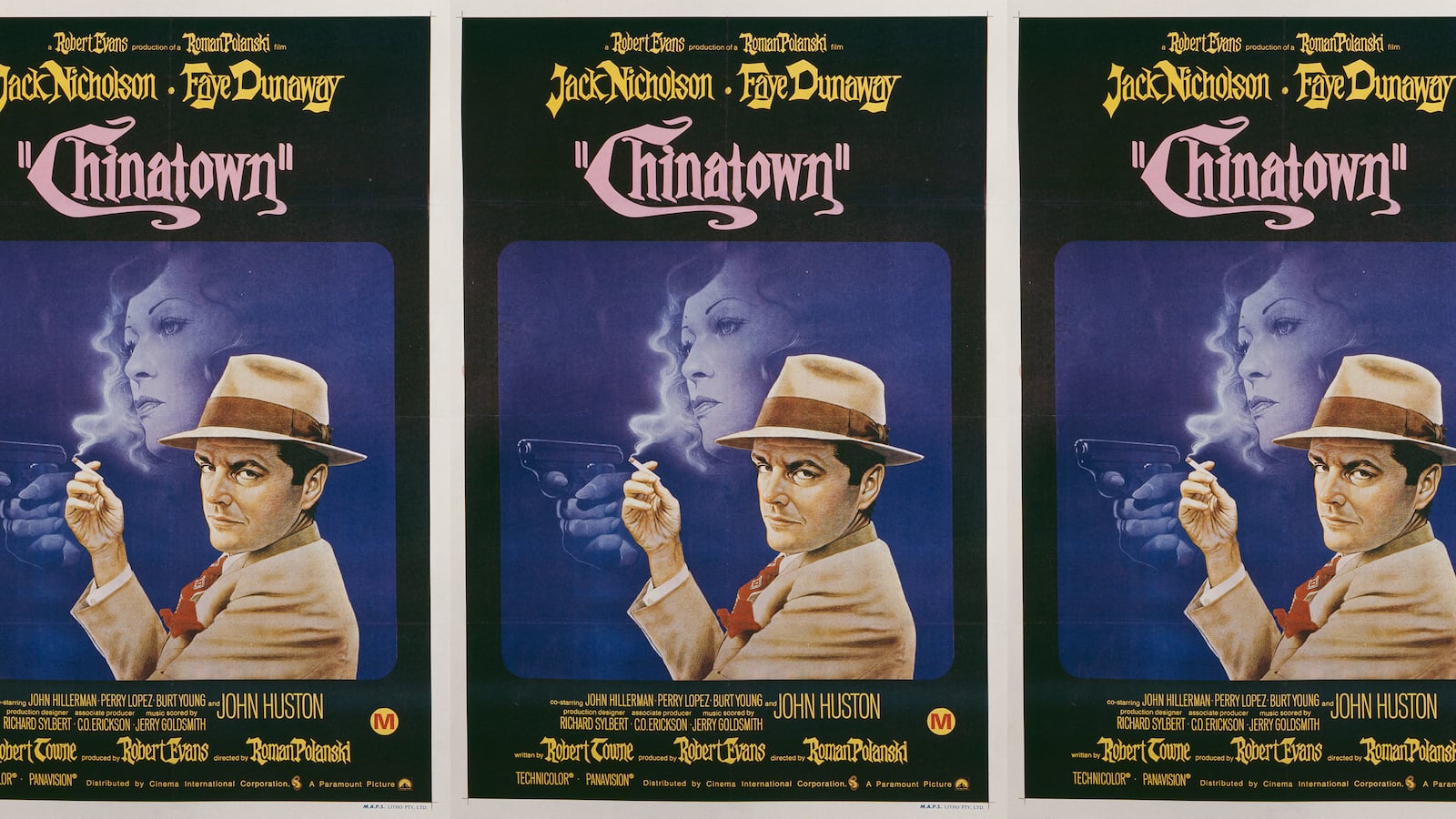

Chinatown’s throwback opening credits and Jerry Goldsmith’s score establish the ’30s mood of the movie’s plot, creating that world right from the typeface. Nicholson’s first appearance frames him at his desk in perfect lighting, making a practiced spin to a liquor cabinet, pouring cuckold Burt Young a shot of whiskey. Each of them acts with an almost affected sense of performance, aware they are moving, speaking ingredients of a larger whole.

Wasson showcases Polanski the director within the creative process of the film set. Polanski’s vision smoothed out Chinatown with color and light, shadow and framing—a Los Angeles of style and California cool, hiding the irredeemable rot of a villain like Noah Cross; by the uncharitable, the comparison could be considered subtext for Polanski himself.

“I knew the Polanski of it all would be a challenge for some people,” said Wasson, “but that inspired me, because I’m all about what’s on the screen.

“Chinatown is an ugly movie. You can’t make a movie like that if you haven’t suffered under corruption, if you don’t know what evil is.”

That doesn’t mean the movie is ever visually ugly. Polanski’s films are “full of elements for the eye to enjoy; those inner contradictors and complexity make the movies so good,” Wasson told The Daily Beast. “The work itself is often very funny. Horror doesn’t walk in the door looking like a bad guy.”

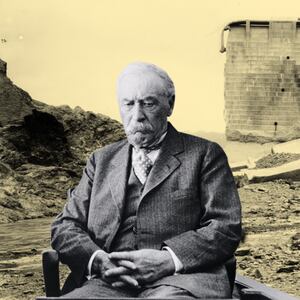

Wasson was referring to demonic Ruth Gordon from Polanski’s earlier Rosemary’s Baby, but it applies to John Huston’s avuncular Noah Cross. After all, the incestuous Cross’ worst on-screen act is only mispronouncing Gittes’ name with a bemused contempt.

As Wasson writes, that lack of obvious threat can apply to Polanski in 1977, presenting a 13-year-old girl with a bottle of champagne: “Should I open it?” And suggesting to her, “Let’s take some photos in the Jacuzzi.”

It’s easy, with such a history, to see Polanski as only another Noah Cross deserving no redemption or empathy. Getting away with it.

Thirty-six years before Polanski had access to Jacuzzis in mansions on Mulholland Drive, Wasson writes that Roman’s father “Ryszard hugged and held [Roman] with unsettling intensity… on Podgorze Bridge, returning to the Warsaw ghetto, he was weeping uncontrollably: ‘They took your mother…’” Bula Polanski, taken by the Nazis to her death, was pregnant at the time.

In August 1969, Polanski was in England where he took a call from his agent Bill Tennant: “There was a disaster in the house.”

Polanski “heard the words, but he did not understand, because the words were not true. They just had spoken.”

Sharon Tate was eight months pregnant when she was murdered. The deaths, the manhunt, the trials, the notoriety, the war, the Holocaust, the camps, all inescapable, a drumbeat of memory without respite.

“You have to show violence the way it is,” Polanski would say. “If you don’t upset people, then that’s obscenity.”

In Chinatown, Polanski used himself to play the Cross henchman who slashed Nicholson’s nose, filming take after take with a dangerous spring-loaded knife.

He posed and reposed the prone actress playing a murdered woman for a five-second scene: “‘And the leg’—he bent the leg unnaturally and stood up to assess the results—‘it is right.’”

“Everyone thought Roman was replaying the death of his wife,” the actress, Diane Ladd, told Wasson. “It was a very scary day.”

Wasson does not use the term Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. He provides examples of behavior by a man who lost his pregnant mother and pregnant wife to violence.

“All I could do is tell a story that unfolds like a Greek tragedy,” Wasson said. “Roman’s not the only person who survived the Holocaust. I’m not inclined to say X caused Y. I’m in the grey. Bad things happened to him, and he did bad things.”

Within that gray is the art of Chinatown made by people with self-destructive flaws, some risen to crimes like Polanski’s, others melancholy like Jack Nicholson’s star-crossed love and infidelity toward Angelica Huston, or producer Robert Evans’ cocaine habit and the slow-slipping loss of his magic touch, and Towne’s awful behavior toward his ex-wife and unshared credit with a hidden writing partner. After the picture wrapped, they all slouch toward private Bethlehems of their futures.

Nicholson comes off the best, despite any number of personal mistakes.

“Writing about Jack, who’s had a career this long, I got to see what’s consistent, going back to before he was famous,” Wasson said. “It was nice to really walk around in those shoes.”

Nicholson wasn’t interviewed for the book, though Wasson mined numerous articles for Nicholson’s previous commentary. One has to think Nicholson is content with society’s current memory of him and his career.

As recapped by Wasson, Chinatown’s final scene provides that insight into how audiences choose what to remember—or what version of a tragedy sticks in the heart. As they filmed the movie’s violent climax, Polanski’s focus was Nicholson’s final line, “as little as possible,” murmured by Jake Gittes, staring at Evelyn Mulwray’s corpse in the car, shot through the eye. The line reprises an earlier moment in the film when the cynically confident Gittes is telling Mulwray about his time as a police detective in Chinatown: “What were you doing there?” Faye Dunaway’s Mulwray asks. “As little as possible,” Gittes says.

Wasson recapped, “Now, in the ending,” which Polanski insisted be literally “set in Chinatown, the line would reappear, echoing a note of terrible irony.”

Despite Polanski’s intent, “As little as possible” is not what’s remembered, nor even the defeat it represents. Instead, “Forget it, Jake. It’s Chinatown” became that moment, a shrugging passivity its lasting advice. Best to just fly away.

The movie’s denouement took place on a real-life Chinatown street. Polanski crafted his ending shot as a crane pull-up that climbed above the scene, the little people and their fates: “a sweeping flourish, rising as it does from the ground level of Gittes’ devastation to a more godly vantage point, from despair to a kind of cinema majesty.”

In the narrative of Hollywood, that crane-up provides a perfect segue—that last, big goodbye that Wasson promised.

“Though it offers no hope or resolution,” he wrote, “ending Chinatown with a grand crane-up evokes a lost Hollywood… imbuing the wreckage with a shiver of romantic awe, not just in the movement itself, the feeling of sudden floating, but in a kind of longing for tradition that might be called classical.”

What comes next are movies like Jaws and Star Wars, of course, the summer blockbusters that changed the game as far as movie production--but Billy Jack, a low-budget populist action pic came first. Opened simultaneously in 60 L.A. theaters, Billy Jack made a million dollars in six days, and $32 million overall; Wasson writes that when Warners applied the same “four-walling” strategy, opening simultaneously in as many theaters as possible, to The Exorcist, it grossed $160 million.

As recaptured by Wasson, Chinatown feels apart from that drive for profit; a stately pace, only short splashes of action, and a menacing silence characterize the film. The ugliness succeeds through captivation. Like the California dam disaster that is part of the movie’s water-related plot, the pressure builds quietly, then all at once. A metaphor for 1973 Hollywood.

Wasson writes: “When he heard about [The Exorcist] gross, Warners executive Dick Lederer walked into executive Barry Beckerman’s office and threw The Exorcist numbers down in front of him.

“Kid, the fun is over,” Lederer announced. “We’ve been having a good time out here and been very successful, but it’s gonna get real serious after this.”

Chinatown’s first location shoot was Oct. 15, 1973, the chase in the orchard. On Oct. 26, Martin Scorsese’s Mean Streets opened in Los Angeles. A banner blurb on its full-page ad in The Los Angeles Times said the movie “doesn’t just explode—it erupts with volcanic force.” The writer was the same Jon Landau who would call Bruce Springsteen the future of rock ’n’ roll.

Mean Streets opens with natural street lighting, a jerky camera filming Harvey Keitel waking from a nightmare, bathed in blue neon. Ronnie Spector’s “Be My Baby” pounds into the speakers, the opening credits a montage of cuts and sound—a Wall of Sound, just like Phil Spector intended.

Chinatown cinematographer John Alonzo was unimpressed with Polanski’s ending crane shot: “Roman, you’re contriving a shot. You’re contriving it because you don’t know how to end the picture. You’re performing cinematic gymnastics.” He couldn’t see a point in an affected flourish.

What would Alonzo have said to Scorsese? Mean Streets used tracking shots from just over Keitel’s head as he strolls through a strip club; Robert DeNiro enters a scene to the Rolling Stones “Jumping Jack Flash;” the camera pans half-speed down a bar. In 1973, it must have felt unrecognizable.

After Mean Streets came The Exorcist, Dog Day Afternoon, Saturday Night Fever, Network; character and plot, but also action, frenzy, movement, motion, sound, all in a rush.

Single moments might seem quaint. Polanski filmed the famous “my sister, my daughter” scene, and the impact sharpens because overt violence is uncommon in the film. Gittes loses his cool, slapping Dunaway’s Evelyn Mulwray across her face, again and again. Nicholson felt nervous about the scene, didn’t want to hit a woman, showing it with his ice-cold expression. Unlike Mean Streets, with flourishes and spins and sounds in every scene, Polanski frames Nicholson’s cold stare, Dunaway’s unhinged eyes, and the horror of two shattered people meant to blow up on a 60-foot screen. It’s personal.

“Between takes, Dunaway would look over to her director,” Wasson writes. “She thought, he’s enjoying this moment far too much. The young girls, his sarcasm and needless cruelty, directing movies. It was about power for him. All of it. Her face burned where Jack’s slaps had landed… her neck ached.

“‘Once more please, fellows,’ her director said. ‘Once more…’”

Chinatown the movie ends with the crane lifting away from Gittes failure, Mulwray’s corpse, and Noah Cross’ triumph—in real life, that climb kept going, above the finale’s defeat and cynicism: “The only place left to go was up, to The Sting, to Happy Days, to ‘a mix of nostalgia and parody,’ the mass denial of the terrible truths Gittes was powerless to undo,” Wasson writes.

“That look on Jack’s face at the end, he looks lobotomized. It’s not an accident,” Wasson told the Beast, how Nicholson’s performance captures the devastation of calling every shot wrong, of being on the wrong side. It’s finally too hard to keep looking—“forget it, Jake,” indeed.

Producer Robert Evans died late last year; his interviews were with Wasson, “hours and hours” of storytelling, looking back, about long ago. Evans and Wasson explain the creation of Chinatown’s score, composed by Jerry Goldsmith, notable for Uan Rasey’s melancholy trumpet. Goldsmith narrates California, connecting sound with sight, a mournful sound for bleak scenes.

Wasson told the Beast his book is also an attempt at connection, a message in a bottle: “What’s the purpose of biography, of art? To get close to these things, to greatness and to danger, to understand what makes these things happen. I like to be around people who will teach me.”

Evans told Wasson about hearing Goldsmith’s score: “It was out of the darkness, a faith. The ache, the longing, dying but sweetly pleading, like a happy memory drowning in truth.”

Why read The Big Goodbye, about Chinatown’s creation by flawed visionaries? Why remember?

“The sound stunned Evans. Like Polanski’s crane, a lift, redemption, grace. The feeling was that word he lost so much trying to find and hold on to—‘romance.’” Star-crossed, I’m sure he meant, the wistful kind of sorrow.